The New Penguin History of the World (141 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

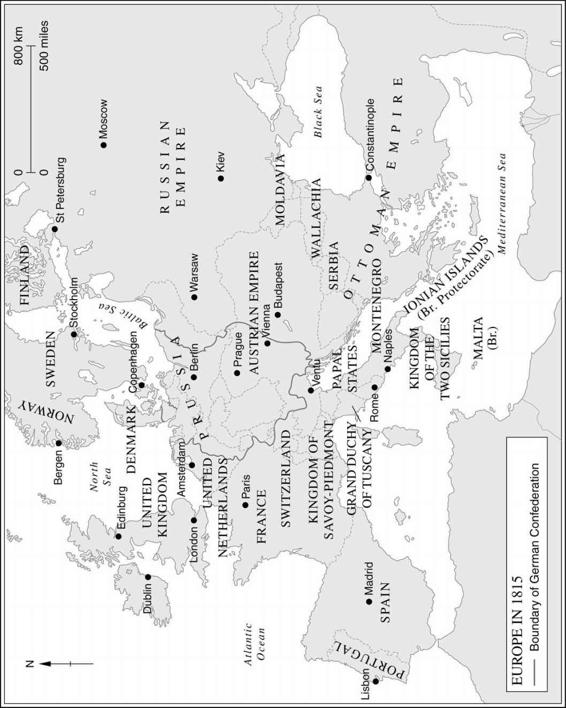

This was symptomatic. The revolutionaries of 1848 were provoked by very different situations, had many different aims, and followed divergent and confusing paths. In most of Italy and central Europe they rebelled against governments which they thought oppressive because they were illiberal; there, the great symbolic demand was for constitutions to guarantee essential freedoms. When such a revolution occurred in Vienna itself, the chancellor Metternich, architect of the conservative order of 1815, fled into exile. Successful revolution at Vienna meant the paralysis and therefore the dislocation of the whole of central Europe. Germans were now free to have their revolutions without fear of Austrian intervention in support of the

ancien régime

in the smaller states. So were other peoples within the Austrian dominions; Italians (led by an ambitious but apprehensive conservative king of Sardinia) turned on the Austrian armies in Lombardy and Venetia, Hungarians revolted at Budapest, and Czechs at Prague. This much complicated things. Many of these revolutionaries wanted national independence rather than constitutionalism, though constitutionalism seemed for a time the way to independence because it attacked dynastic autocracy.

If the liberals were successful in getting constitutional governments installed in all the capitals of central Europe and Italy, then it followed there would actually come into existence nations hitherto without state structures of their own, or at least without them for a very long time. If Slavs achieved their own national liberation then states previously thought of as German would be shorn of huge tracts of their territory, notably in Poland and Bohemia. It took some time for this to sink in. The German

liberals suddenly fell over this problem in 1848 and quickly drew their conclusions; they chose nationalism. (The Italians were still grappling with their own version of the dilemma in the South Tyrol a hundred years later.) The German revolutions of 1848 failed, essentially, because the German liberals decided that German nationalism required the preservation of German lands in the east. Hence, they needed a strong Prussia and must accept its terms for the future of Germany. There were other signs, too, that the tide had turned before the end of 1848. The Austrian army had mastered the Italians. In Paris a rising aiming to give the Revolution a further shove in the direction of democracy was crushed with great bloodshed in June. The republic was, after all, to be a conservative one. In 1849 came the end. The Austrians overthrew the Sardinian army which was the only shield of the Italian revolutions, and monarchs all over the peninsula then began to withdraw the constitutional concessions they had made while Austrian power was in abeyance. German rulers did the same, led by Prussia. The pressure was kept up on the Habsburgs by the Croats and Hungarians, but then the Russian army came to its ally’s help.

Liberals saw 1848 as a ‘springtime of the nations’. If it was one, the shoots had not lived long before they withered. By the end of 1849 the formal structure of Europe was once again much as it had been in 1847, in spite of important changes within some countries. Nationalism had certainly been a popular cause in 1848, but it had been neither strong enough to sustain revolutionary governments nor obviously an enlightened force. Its failure shows that the charge that the statesmen of 1815 ‘neglected’ to give it due attention is false; no new nation emerged from 1848 for none was ready to do so. The basic reason for this was that although nationalities might exist, over most of Europe nationalism was still an abstraction for the masses; only relatively few and well-educated, or at least half-educated, people much cared about it. Where national differences also embodied social issues there was sometimes effective action by people who felt they had an identity given them by language, tradition or religion, but it did not lead to the setting up of new nations. The Ruthene peasants of Galicia in 1847 had happily murdered their Polish landlords when the Habsburg administration allowed them to do so. Having thus satisfied themselves they remained loyal to the Habsburgs in 1848.

There were some genuinely popular risings in 1848. In Italy they were usually revolts of townsmen rather than peasants; the Lombard peasants, indeed, cheered the Austrian army when it returned, because they saw no good for them in a revolution led by the aristocrats who were their landlords. In parts of Germany, over much of which the traditional structures of landed rural society remained intact, the peasants behaved as their

predecessors had done in France in 1789, burning their landlords’ houses, not merely through personal animus but in order to destroy the hated and feared records of rents, dues and labour services. Such outbreaks frightened urban liberals as much as the Parisian outbreak of despair and unemployment in the June Days frightened the middle classes in France. There, because the peasant was since 1789 (speaking broadly) a conservative, the government was assured of the support of the provinces in crushing the Parisian poor who had given radicalism its brief success. But conservatism could be found within revolutionary movements, too. German working-class turbulence alarmed the better-off, but this was because the leaders of German workers talked of ‘socialism’ while actually seeking a return to the past. They had the safe world of guilds and apprenticeships in mind, and feared machinery in factories, steamboats on the Rhine, which put boatmen out of work, the opening of unrestricted entry to trades – in short, the all-too-evident signs of the onset of market society. Almost always, liberalism’s lack of appeal to the masses was shown up in 1848 by popular revolution.

Altogether, the social importance of 1848 is as complex and escapes easy generalization as much as its political content. It was probably in the countryside of eastern and central Europe that the revolutions changed society most. There, liberal principles and the fear of popular revolt went hand in hand to impose change on the landlords. Wherever outside Russia obligatory peasant labour and bondage to the soil survived, it was abolished as a result of 1848. That year carried the rural social revolution, launched sixty years earlier in France, to its conclusion in central and most of eastern Europe. The way was now open for the reconstruction of agricultural life in Germany and the Danube valley on individualist and market lines. Though many of its practices and habits of mind were still to linger, feudal society was in effect now coming to an end all over Europe. The political components of French revolutionary principles, though, would have to wait longer for their expression.

In the case of nationalism this was not very long. A dispute over Russian influence in the Near East in 1854 ended the long peace between the great powers which had lasted since 1815. The Crimean War, in which the French and British fought as allies of the Ottoman Sultan against the Russians, was in many ways a notable struggle. Fighting took place in the Baltic, in southern Russia, and in the Crimea, the last theatre attracting most attention. There, the allies had set themselves to capture Sebastopol, the naval base which was the key to Russian power in the Black Sea. Some of the results were surprising. The British army fought gallantly, as did its opponents and allies, but was especially distinguished by the inadequacy of its administrative arrangements; the scandal these caused launched an important wave of radical reform at home. Incidentally the war also helped to found the prestige of a new profession for women, that of nursing, for the collapse of British medical services had been particularly striking. Florence Nightingale’s work launched the first major extension of the occupational opportunities available to respectable women since the creation of female religious communities in the Dark Ages. The conduct of the war is also noteworthy in another way as an index of modernity: it was the first between major powers in which steamships and a railway were employed, and it brought the electric telegraph cable to Istanbul.

Some of these things were portentous. Yet they mattered less in the short run than what the war did to international relations. Russia was defeated and her long enjoyment of a power to intimidate Turkey was bridled for a time. A step was taken towards the establishment of another new Christian nation, Romania, which was finally brought about in 1862. Once more, nationality triumphed in former Ottoman lands. But the crucial effect of the war was that the Holy Alliance had disappeared. The old rivalry of the eighteenth century between Austria and Russia over what would happen to the Ottoman inheritance in the Balkans had broken out again when Austria warned Russia not to occupy the Danube principalities (as the future Romania was termed) during the war and then occupied them herself. This

was five years after Russia had intervened to restore Habsburg power by crushing the Hungarian revolution. It was the end of friendship between the two powers. The next time Austria faced a threat she would have to do so without the Russian policeman of conservative Europe at her side.

In 1856, when peace was made, few people can have anticipated how quickly that time would come. Within ten years Austria lost in two short, sharp wars her hegemony both in Italy and in Germany, and those countries were united in new national states. Nationalism had indeed triumphed, and at the cost of the Habsburgs, as had been prophesied by enthusiasts in 1848, but in a totally unexpected way. Not revolution, but the ambitions of two traditionally expansive monarchical states, Sardinia and Prussia, had led each to set about improving its position at the expense of Austria, whose isolation was at that moment complete. Not only had she sacrificed the Russian alliance, but after 1852 France was ruled by an emperor who again bore the name Napoleon (he was the nephew of the first to do so). He had been elected president of the Second Republic, whose constitution he then set aside by

coup d’état

. The name Napoleon was itself terrifying. It suggested a programme of international reconstruction – or revolution. Napoleon III (the second was a legal fiction, a son of Napoleon I who had never ruled) stood for the destruction of the anti-French settlement of 1815 and therefore of the Austrian predominance which propped it up in Italy and Germany. He talked the language of nationalism with less inhibition than most rulers and seems to have believed in it. With arms and diplomacy he forwarded the work of two great diplomatic technicians, Cavour and Bismarck, the prime ministers respectively of Sardinia and of Prussia.

In 1859 Sardinia and France fought Austria; after a brief war the Austrians were left with only Venetia in Italy. Cavour now set to work to incorporate other Italian states into Sardinia, a part of the price being that Sardinian Savoy had to be given to France. Cavour died in 1861, and debate still continues over what was the real extent of his aims, but by 1871 his successors had produced a united Italy under the former King of Sardinia, who was thus recompensed for the loss of Savoy, the ancestral duchy of his house. In that year Germany was united, too. Bismarck had begun by rallying German liberal sentiment to the Prussian cause once again in a nasty little war against Denmark in 1864. Two years later Prussia defeated Austria in a lightning campaign in Bohemia, thus at last ending the Hohenzollern–Habsburg duel for supremacy in Germany begun in 1740 by Frederick II. The war which did this was rather a registration of an accomplished fact than its achievement, for since 1848 Austria had been much weakened in German affairs. In that year, German liberals had offered a German crown, not to the emperor, but to the King of Prussia.

Nevertheless, some states had still looked to Vienna for leadership and patronage, and they were now left alone to meet Prussian bullying. The Habsburg empire now became wholly Danubian, its foreign policy preoccupied with south-east Europe and the Balkans. It had retired from the Netherlands in 1815, Venetia had been exacted by the Prussians for the Italians in 1866, and now it left Germany to its own devices, too. Immediately after the peace the Hungarians seized the opportunity to inflict a further defeat on the humiliated monarchy by obtaining a virtual autonomy for the half of the Habsburg monarchy made up of the lands of the Hungarian Crown. The empire thus became, in 1867, the Dual or Austro-Hungarian monarchy, divided rather untidily into two halves linked by little more than the dynasty itself and the conduct of a common foreign policy.

German unification required one further step. It had gradually dawned on France that the assertion of Prussian power beyond the Rhine was not in the French interest; instead of a disputed Germany, she now faced one dominated by an important military power. The Richelieu era had crumbled away unnoticed. Bismarck used this new awareness, together with Napoleon III’s weaknesses at home and international isolation, to provoke France into a foolish declaration of war in 1870. Victory in this war set the coping-stone on the new edifice of German nationality, for Prussia had taken the lead in ‘defending’ Germany against France – and there were still Germans alive who could remember what French armies had done in Germany under an earlier Napoleon. The Prussian army destroyed the Second Empire in France (it was to be the last monarchical regime in that country) and created the German empire, the Second Reich, as it was called, to distinguish it from the medieval empire. In practice, it was a Prussian domination cloaked in federal forms, but as a German national state it satisfied many German liberals. It was dramatically and appropriately founded in 1871 when the king of Prussia accepted the crown of united Germany (which his predecessor had refused to take from German liberals in 1848) from his fellow princes in the palace of Louis XIV at Versailles.