The New Penguin History of the World (15 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

Dynasties | |

I–II | Protodynastic |

III–VIII | Old Kingdom 2686–2160 |

IX–XI | First Intermediate 2160–2055 |

XII–XIV | Middle Kingdom 2055–1650 |

XV–XVII | Second Intermediate 1650–1550 |

XVIII–XX | New Kingdom 1550–1069 |

This takes us down to the time at which, as in Mesopotamian history, there is something of a break as Egypt is caught up in a great series of upheavals originating outside its own boundaries to which the overworked word ‘crisis’ can reasonably be applied. True, it is not until several more centuries have passed that the old Egyptian tradition really comes to an end. Some modern Egyptians insist on a continuing sense of identity among Egyptians since the days of the Pharaohs. None the less, somewhere about the beginning of the first millennium is one of the most convenient places at which to break the story, if only because the greatest achievements of the Egyptians were by then behind them.

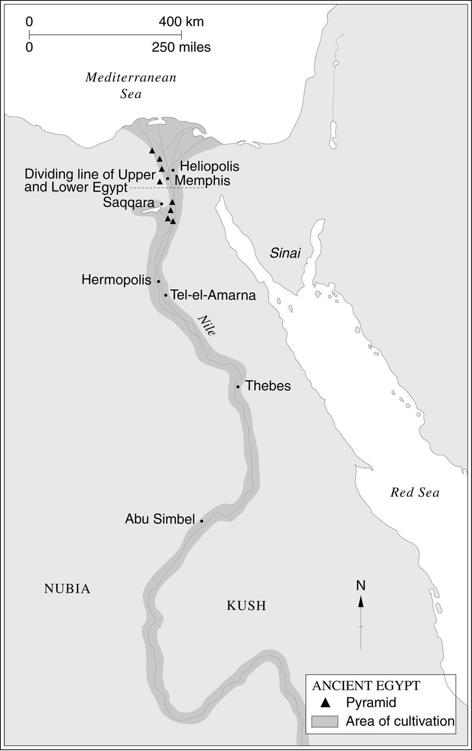

These were above all the work of and centred in the monarchical state. The state form itself was the expression of Egyptian civilization. It was focused first at Memphis whose building was begun during the lifetime of

Menes and which was the capital of the Old Kingdom. Later, under the New Kingdom, the capital was normally at Thebes, though there were also periods of uncertainty about where it was. Memphis and Thebes were great religious centres and palace complexes; they did not really progress beyond this to true urbanism. The absence of cities earlier was politically important, too. Egypt’s kings had not emerged like Sumer’s as the ‘big men’ in a city-state community which originally deputed them to act for it. Nor were they simply men who like others were subject to gods who ruled all men, great or small. They were mediators between their subjects and unearthly powers. The tension of palace with temple was missing in Egypt and when Egyptian kingship emerges it is unrivalled in its claims. The Pharaohs were to be gods, not servants of gods.

It was only under the New Kingdom that the title ‘pharaoh’ came to be applied personally to the king. Before that it indicated the king’s residence and his court. None the less, at a much earlier stage Egyptian monarchs already had the authority which was so to impress the ancient world. It is expressed in the exaggerated size with which they are depicted on the earliest monuments. This they inherited ultimately from prehistoric kings who had a special sanctity because of their power to assure prosperity through successful agriculture. Such powers are attributed to some African rainmaker-kings even today; in ancient Egypt they focused upon the Nile. The Pharaohs were believed to control its annual rise and fall: life itself, no less, to the riparian communities. The first rituals of Egyptian kingship known to us are concerned with fertility, irrigation and land reclamation. The earliest representations of Menes show him excavating a canal.

Under the Old Kingdom the idea appears that the king is the absolute lord of the land. Soon he is venerated as a descendant of the gods, the original lords of the land. He becomes a god, Horus, son of Osiris, and takes on the mighty and terrible attributes of the divine maker of order; the bodies of his enemies are depicted hanging in rows like dead gamebirds, or kneeling in supplication lest (like less fortunate enemies) their brains be ritually dashed out. Justice is ‘what Pharaoh loves’, evil ‘what Pharaoh hates’; he is divinely omniscient and so needs no code of law to guide him. Later, under the New Kingdom, the Pharaohs were to be depicted with the heroic stature of the great warriors of other contemporary cultures; they are shown in their chariots, mighty men of war, trampling down their enemies and confidently slaughtering beasts of prey. Perhaps a measure of secularization can be inferred in this change, but it does not remove Egyptian kingship from the region of the sacred and awesome. ‘He is a god by whose dealings one lives, the father and mother of all men, alone by himself, without an equal’, wrote one of the chief civil servants of the

Pharaoh as late as about 1500

BC

. Until the Middle Kingdom, only he had an afterlife to look forward to. Egypt, more than any other Bronze Age state, always stressed the incarnation of the god in the king, even when that idea was increasingly exposed by the realities of life in the New Kingdom and the coming of iron. Then, the disasters which befell Egypt at the hands of foreigners would make it impossible to continue to believe that Pharaoh was god of all the world.

But long before this the Egyptian state had acquired another institutional embodiment and armature, an elaborate and impressive hierarchy of bureaucrats. At its apex were viziers, provincial governors and senior officials who came mainly from the nobility; a few of the greatest among these were buried with a pomp rivalling that of the Pharaohs. Less eminent families provided the thousands of scribes needed to staff and service an elaborate government directed by the chief civil servants. The ethos of this bureaucracy can be sensed through the literary texts which list the virtues needed to succeed as a scribe: application to study, self-control, prudence, respect for superiors, scrupulous regard for the sanctity of weights, measures, landed property and legal forms. The scribes were trained in a special school at Thebes, where not only the traditional history and literature and command of various scripts were taught, but, it seems, surveying, architecture and accountancy also.

The bureaucracy directed a country most of whose inhabitants were peasants. They cannot have lived wholly comfortable lives, for they provided both the conscript labour for the great public works of the monarchy and the surplus upon which a noble class, the bureaucracy and a great religious establishment could subsist. Yet the land was rich and was increasingly mastered with irrigation techniques established in a pre-dynastic period (probably one of the earliest manifestations of the unsurpassed capacity to mobilize collective effort which was to be one of the hallmarks of Egyptian government). Vegetables, barley, emmer were the main crops of the fields laid out along the irrigation channels; the diet they made possible was supplemented by poultry, fish and game (all of which figure plentifully in Egyptian art). Cattle were in use for traction and ploughing at least as early as the Old Kingdom. With little change this agriculture remained the basis of life in Egypt until modern times; it was sufficient to make her the granary of the Romans.

On the surplus of this agriculture there also rested Egypt’s own spectacular form of conspicuous consumption, a range of great public works in stone unsurpassed in antiquity. Houses and farm buildings in ancient Egypt were built in the mud brick already used before dynastic times: they were not meant to outface eternity. The palaces, tombs and memorials of the Pharaohs were a different matter; they were built of the stone abundantly available in some parts of the Nile valley. Though they were carefully dressed with first copper and then bronze tools and often elaborately incised and painted, the technology of utilizing this material was far from complicated. Egyptians invented the stone column, but their great building achievement was not so much architectural and technical as social and administrative. What they did was based on an unprecedented and almost unsurpassed concentration of human labour. Under the direction of a scribe, thousands of slaves and sometimes regiments of soldiers were deployed to cut and manhandle into position the huge masses of Egyptian building. With only such elementary assistance as was available from levers and sleds – no winches, pulleys, blocks or tackle existed – and by the building of colossal ramps of earth, a succession of still-startling buildings was produced.

They began under the Third Dynasty. The most famous are the pyramids, the tombs of kings, at Saqqara, near Memphis. One of these, the ‘Step Pyramid’, was traditionally seen as the masterpiece of the first architect whose name is recorded – Imhotep, chancellor to the king. His work was so impressive that he was later to be deified, as well as being revered as physician, astronomer, priest and sage. The beginning of building in stone was attributed to him and it is easy to believe that the building of something so unprecedented as the 200-foot-high pyramid was seen as evidence of godlike power. It and its companions rose without peer over a civilization which until then lived only in dwellings of mud. A century or so later, blocks of stone of fifteen tons apiece were used for the pyramid of Cheops or Khufru, and it was at this time (during the Fourth Dynasty) that the greatest pyramids were completed at Giza. Cheops’s pyramid was twenty years in the building; the legend that 100,000 men were employed upon it is now thought to be an exaggeration but many thousands must have been and the huge quantities of stone (between five and six million tons) were brought from as far as 500 miles away. This colossal construction is perfectly orientated and its sides, 750 feet long, vary by less than eight inches – only about 0.09 per cent. The pyramids later figured among the Seven Wonders of the World, and they alone among those Wonders survive. They were the greatest evidence of the power and self-confidence of the pharaonic state. Nor, of course, were they the only great monuments of Egypt. Each of them was only the dominant feature of a great complex of buildings which made up together the residence of the king after death. At other sites there were great temples, palaces, the tombs of the Valley of the Kings.

These huge public works were in both the real and figurative sense the

biggest things the Egyptians left to posterity. They make it less surprising that the Egyptians were later also reputed to have been great scientists: people could not believe that these huge monuments did not rest on the most refined mathematical and scientific skills. Yet this is an invalid inference and untrue. Though Egyptian surveying was highly skilled, it was not until modern times that a more than elementary mathematical skill became necessary to engineering; it was certainly not needed for the erection of the pyramids. What was requisite was outstanding competence in mensuration and the manipulation of certain formulae for calculating volumes and weights, and this was as far as Egyptian mathematics went, whatever later admirers believed. Modern mathematicians do not think much of the Egyptians’ theoretical achievement and they certainly did not match the Babylonians in this art. They worked with a decimal numeration which at first sight looks modern, but it may be that their only significant contribution to later mathematics was the invention of unit fractions.

No doubt a primitive mathematics is a part of the explanation of the sterility of the Egyptians’ astronomical endeavours – another field in which posterity, paradoxically, was to credit them with great things. Their observations were accurate enough to permit the forecasting of the rise of the Nile and the ritual alignment of buildings, it is true, but their theoretical astronomy was left far behind by the Babylonians. The inscriptions in which Egyptian astronomical science was recorded were to command centuries of awed respect from astrologers, but their scientific value was low and their predictive quality relatively short term. The one solid work which rested on the Egyptians’ astronomy was the calendar. They were the first people to establish the solar year of 365¼ days and they divided it into twelve months, each of three ‘weeks’ of ten days, with five extra days at the end of the year – an arrangement, it may be remarked, to be revived in 1793 when the French revolutionaries sought to replace the Christian calendar by one more rational.

The calendar, though it owed much to the observation of stars, must have reflected also in its remoter origins observation of the great pulse at the heart of Egyptian life, the flooding of the Nile. This gave the Egyptian farmer a year of three seasons, each of approximately four months, one of planting, one of flood, one of harvest. But the Nile’s endless cycle also influenced Egypt at deeper levels.

The structure and solidity of the religious life of ancient Egypt greatly struck other peoples. Herodotus believed that the Greeks had acquired the names of their gods from Egypt; he was wrong, but it is interesting that he should have thought so. Later, the cults of Egyptian gods were seen as a threat by the Roman emperors; they were forbidden, but the Romans

had eventually to tolerate them, such was their appeal. Mumbo-jumbo and charlatanry with an Egyptian flavour could still take in cultivated Europeans in the eighteenth century; an amusing and innocent expression of the fascination of the myth of ancient Egypt could still be seen in recent times in the rituals of the Shriners, the fraternities of respectable American businessmen who paraded about the streets of small towns on great occasions improbably attired in fezzes and baggy trousers. There was, indeed, a continuing vigour in Egyptian religion which, like other sides of Egyptian civilization, long outlived the political forms that had sustained and sheltered it.