The Modern Middle East (16 page)

Read The Modern Middle East Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Middle Eastern, #Religion & Spirituality, #History, #Middle East, #General, #Political Science, #Religion, #Islam

Others denied the existence of a Palestinian people altogether. Golda Meir, one of Israel’s most celebrated prime ministers, stated this position emphatically: “There was no such thing as Palestinians. . . . They did not exist.”

29

Similarly,

Israel: Personal History,

by David Ben-Gurion—one of the central figures of the Zionist movement and the Jewish state’s first prime minister—is striking in its lack of mention of a previously existing Palestinian population.

30

In his memoirs he wrote: “I believed then, as I do today, that we had a clear title to this country. Not the right to take it away from others (there were no others), but the right and the duty to fill its emptiness, restore life to its barrenness, to re-create a modern version of our own nation. And I felt we owed this effort not only to ourselves but to the land as well.”

31

This viewpoint was most pointedly summed up in the slogan “A land without a people for a people without a land.”

32

The central assumptions of Zionism were that only God’s chosen people should be in the Promised

Land, that the backward trespassers who were there had no rights to it, and that the problems posed by their existence on the land could be easily dispensed with. A passage on the Palestinians from Herzl’s diary, written in 1895, is instructive: “We shall have to spirit the penniless population across the border by procuring employment for it in transit countries, while denying it any employment in our own country. Both the process of expropriation and the removal of the poor must be carried out discreetly and circumspectly.”

33

Some of Herzl’s disciples were not as discreet, nor were they

always willing to pay for Palestinian land. By most accounts, by 1948 only 6 percent of the land belonging to Palestinians had been bought by Zionists.

34

Most houses were either simply destroyed or appropriated. One Israeli researcher has estimated that nearly four hundred Palestinian villages were “completely destroyed, with their houses, garden-walls, and even cemeteries and tombstones, so that literally a stone does not remain standing, and visitors are passing and being told ‘it was all desert.’”

35

Figure 5.

David Ben-Gurion, the first prime minister of the state of Israel. Corbis.

Figure 6.

Israeli women taking an oath to join the Haganah, Tel Aviv, 1948. Corbis.

Many of the demolitions and other similar military operations in the Yishuv were carried out by one of the three active military organizations: the Haganah, the Irgun, and the so-called Stern Gang. The Haganah (literally, “self-defense”) was established in 1920 with a broad-based mandate to defend the burgeoning Jewish community in Palestine. Initially under the control of the Histadrut labor federation, the Haganah had ready access to a pool of eager volunteers and, under the command of former officers from the USSR and elsewhere, soon acquired an increasingly professional character. From the 1920s to the 1940s, the Haganah maintained an uneasy relationship with the British mandatory authorities: sometimes it was aided by a Bible-wielding, pro-Zionist British commander, Captain Orde Wingate, who collaborated with it against Vichy-dominated Syria; at other times it

was declared illegal and its members were arrested.

36

Nevertheless, throughout, the Haganah secretly registered men and women volunteers and continued to grow. It was eventually amalgamated into the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) once that organization became the new state’s army.

A splinter military organization called the Irgun Zvai Leumi (National Military Organization), alternately referred to as the Etzel or the Irgun, was established in 1937 as a result of the withdrawal of an extremist group known as the Revisionists from the World Zionist Organization. Even more extreme was the group commonly known as the Stern Gang after the name of its founder, Avraham Stern, or, more officially, Fighters for the Freedom of Israel (Lehi for short). Both the Irgun and the Stern Gang rejected the Haganah’s concept of “active defense.” Instead, they launched an intensive campaign of shooting opponents and bombing both British and Palestinian targets. One of the Irgun’s more infamous operations was the bombing of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem on July 22, 1946, in which ninety-one Britons, Palestinians, and Jews were killed and another forty-five were injured.

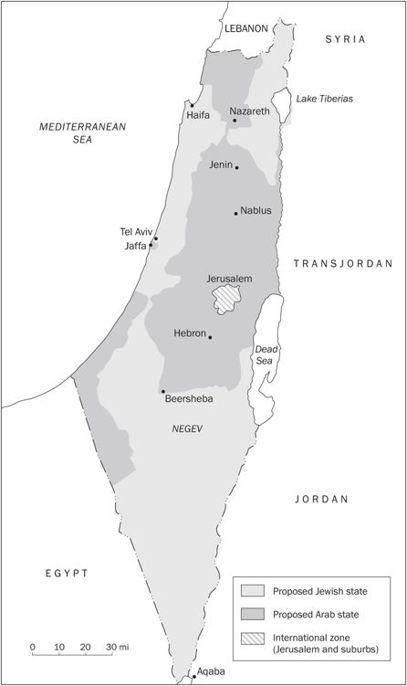

By the late 1940s, exhausted by the war in Europe, Britain was desperately searching for a way to end its mandatory rule over Palestine and simply leave. Earlier, from 1936 to 1939, it had also been forced to contend with an “Arab Revolt,” the fallout from which had only heightened Zionist extremism and terrorist attacks on British as well as Arab targets. The years 1947 and 1948 turned out to be fateful, for the British withdrawal from one town and region after another set off a frantic race between Zionist and Palestinian forces to gain control of the installations and command structures the British were leaving behind. Britain decided to turn over the responsibility for the mandate to the United Nations, which on November 29, 1947, adopted Resolution 181, calling for the partition of Palestine into a separate Arab and a Jewish state, with Bethlehem and Jerusalem retaining international status (map 4). The UN Partition Plan, as the resolution came to be known, was highly favorable to the Zionists, who quickly accepted it, but was rejected by the outraged Palestinians.

37

Although at the time Jews made up only about 33 percent of the inhabitants of Palestine and owned between 6 and 7 percent of the land, the plan awarded the Jewish state 55 percent of historic Palestine, most of it fertile. The area under Jewish control was also to include some 45 percent of the Palestinian population. The proposed Arab state, however, was given only 45 percent of the total land in dispute, much of it not fit for agriculture, and was to include a negligible Jewish minority. Jerusalem and Bethlehem were to remain under UN jurisdiction, and Jaffa, though geographically separated from the rest of the Arab state, was to be a part of it.

Map 4.

The United Nations Partition Plan

The Jewish acceptance and Arab rejection of the UN Partition Plan became the subject of great historical controversy, often cited by subsequent Israeli sources as an example of the Zionists’ desire for peaceful diplomacy and the Arabs’ determination to wage war on Jews.

38

But more recently there emerged in Israel a group of so-called new historians whose documentary and interpretative analysis of the events leading up to and following the creation of the state of Israel fundamentally challenged many of the “myths” of what had actually happened in 1947 and 1948.

39

Among them was the intellectual and longtime political activist Simha Flapan (d. 1987), who had the following interpretation of the Zionists’ acceptance of the plan: “The acceptance of the UN Partition resolution was an example of Zionist pragmatism par excellence. It was a tactical acceptance, a vital step in the right direction—a springboard for expansion when circumstances proved more judicious. And, indeed, in the period between the UN vote on November 29, 1947, and the declaration of the state of Israel on May 14, 1948, a number of developments helped to produce the judicious circumstances that would enable the embryonic Jewish state to expand its border.”

40

Soon after the announcement of the Partition Plan and its aftermath, between December 1947 and May 1948, Palestine was systematically extinguished and a new country, the state of Israel, was created in its place. The death of a country and the birth of a new one are momentous, historic events. The fact that the country being born then was Israel, whose people had lived through the barbarity of the Final Solution and the Holocaust, made the birth all the more momentous. Numerous historians have participated in the celebratory retelling of this birth story, and accounts for Western audiences often highlight joyous tears, hard work, perseverance, and triumph.

41

True as they may be, these accounts are often woefully incomplete, for they say nothing of the other, concurrent development, a country’s death, or of how that death occurred. But the historical record cannot be ignored.

According to one estimate, by 1948, Palestinian forces totaled around seven thousand fighters, including two separate volunteer forces, local rural militias, and various youth defense groups. Zionist forces, meanwhile, including the Haganah, the Irgun, the Stern Gang, and alleged professional volunteers from abroad, swelled from fifteen thousand to sixty thousand.

42

A protracted conflict started soon after the UN vote on the Partition Plan—more sporadic Zionist-Palestinian conflicts had in fact been going on for some time—and a major Jewish military assault was launched in April 1948. One of the darker episodes of Israeli history occurred on April 9,

when more than two hundred inhabitants of the Palestinian village of Deir Yassin were massacred, their bodies subsequently mutilated and dumped in wells.

43

Other cities and villages were quick to fall—Haifa, Jaffa, West Jerusalem, and eastern Galilee all in less than a week in late April, followed by equally decisive victories in the first two weeks of May. “The attacks were brutal,” write two scholars. “Through terror, psychological warfare, and direct conquests, Palestine was dismembered, many of its villages purposefully destroyed and much of its people expelled as refugees.”

44

A massive Palestinian exodus out of Palestine was thus set in motion. Israeli sources put the number of refugees at 520,000, while Arab sources estimate the number to be anywhere between 750,000 and 1,000,000.

45

Like so much else in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, the exact causes of the exodus are still debated and discussed.

46

Contrary to the long-accepted proposition that Arab radio broadcasts encouraged Palestinians to leave, it is now almost uniformly accepted that such broadcasts did not exist and that most Palestinians were in fact urged not to abandon their homes and communities.

47

Instead, the exodus appears to have been the result of two primary factors. Sheer terror appears to have been most compelling, with many Palestinians fearing a fate similar to that of Deir Yassin’s inhabitants. Psychological warfare only fueled Palestinian fears, as pamphlets dropped from the air warned Palestinians of the risks they faced if they stayed behind.

48

Researchers later found that rumors of rape of women by Israeli soldiers and other “Jewish whispering operations” accounted for the movement of a significant percentage of Palestinians.

49

Equally instrumental were a variety of military actions. Notable was the Haganah’s systematic depopulation campaign, aimed at clearing out clusters of Palestinians in the areas it considered to be territorially and strategically important. This campaign was officially adopted in May and June 1948 under the auspices of Plan Dalet, the basic premise of which was “the expulsion over the borders of the local Arab population in the event of opposition to our attacks.”

50

According to the Israeli historian Ilan Pappe,