The Mapmaker's Wife (20 page)

Read The Mapmaker's Wife Online

Authors: Robert Whitaker

Tags: #History, #World, #Non-Fiction, #18th Century, #South America

Even though sour grapes may have affected Cassini’s criticisms, from a scientific point of view, he did have a point. The Lapland expedition had measured only one degree, and upon close inspection, its results did not match up with Newton’s mathematical equations.

“This flatness [of the earth] appears even more considerable than Sir Isaac Newton thought it,” Maupertuis admitted. “I am likewise of the opinion that gravity increases more towards the pole and diminishes more towards the equator than Sir Isaac supposed.” Something was not quite right with their measurement. The controversy was still alive. A famous Scottish mathematician, James Stirling, declared that he would

“choose to stay [neutral] till the French arrive from the South, which I hear will be very soon.” Similarly, Clairaut, in the letter he wrote to La Condamine, noted that the dispute remained so violent that the Peruvian findings were vital to confirming their work in Lapland.

Clairaut had meant to encourage La Condamine with such words, but they had the exact opposite effect.

Vital to confirming the Lapland work

—this was just what the Peruvian team had always feared. They had been away from France three and one-half years, they were still less than halfway done, and they were now in the position of being viewed by history as having come in second, with all the scientific glory going to Maupertuis. Their own experiments with the pendulum had already led them to suspect that Newton was right, that the earth was flattened at the poles and that Cartesian physics would have to be scrapped. Should they continue their triangulation work another year—or longer—simply to bring this debate to a tidier conclusion?

R

IOBAMBA

, where they had stopped for rest in October 1738, turned out to be just the place for them to mull over this question and to rethink their expedition. Although smaller than Quito, this city, tucked in the shadow of Mount Chimborazo, was one of the

most sophisticated cities in all of Peru, perhaps second only to Lima in this regard. Artisans of all kinds—jewelry makers, painters, sculptors, musicians, and carpenters—lived in Riobamba, and a number of Peru’s most prominent families had come here to live, drawn by the pleasant climate and the city’s reputation as a place of culture. This was the birthplace of the Maldonados, and both Pedro and Ramon Maldonado had become so close to the expedition that they had loaned La Condamine and Louis Godin several thousand pesos. The

“agreeable reception provided us [in Riobamba],” La Condamine wrote, “helped us forget the hard times we had spent on their mountains.” The arts, he added, “which were barely cultivated in the province of Quito, seemed to flourish here.” There were Jesuits in Riobamba who spoke French, the town council welcomed them with great warmth, and all of the best families competed to entertain the French savants in their homes. The teenage children of the family of Don Joseph Davalos even put on a play and concert for the visitors, and La Condamine was clearly smitten by their eldest daughter:

“She possessed every talent. She played the harp, the harpsichord, the guitar, the violin, the flute. … [She had] so many resources to please the world.” La Condamine, so often bashful around women because of his smallpox scars, was close to falling in love, but alas, as he later wrote, “her sole ambition was to become a nun.”

With the comforts of civilization rejuvenating their spirits, the members of the expedition were able to see with a new clarity what they were accomplishing. They were not measuring one degree of latitude but three, and it was hard to imagine that the Lapland group, up and back so quickly, had conducted its triangulation with the same obsessive attention to detail that characterized their work. They also knew that they were accomplishing much more than simply measuring the arc at the equator. The very enterprise was forcing them to deepen their understanding of the physical properties of the world. They had needed to investigate the atmosphere’s refractory properties, Bouguer concluding that

“contrary to all received opinion [it] diminished in proportion as we were

above the level of the sea.” They had developed a better understanding of how barometric pressure varied with altitude. They had studied the expansion and contraction of metals in response to temperature change in order to understand how their toise might shrink in the cold. They had needed to perform all these investigations because, in one manner or another, these factors would have to be accounted for in their final calculations of the distance of a degree of latitude at the equator. On this expedition, they were advancing the

art

of doing science, and learning about nature as they did so.

They were aware too that measuring the arc was not the expedition’s only purpose. They were also unveiling a continent. They were investigating its flora and fauna, with Jussieu gathering bags full of seeds and plants to bring back to France. They were making observations on the social mores and customs of colonial Spain. They were newly curious about earthquakes and volcanoes, and a volcano to the southeast of Riobamba, Mount Sangay, was threatening to erupt even as they convalesced in the city. A few months earlier, La Condamine and Bouguer had climbed to a height never before reached by Europeans, and perhaps by no one on earth. Their stay in Riobamba was giving them an opportunity to nurse their tired spirits and heal their bodies, and soon they could appreciate that they had been set loose in a savant’s playground. Even Bouguer, so often grumpy about the rigors of this trip, was ready to change his tune.

“Nature,” he wrote, “has here continually in her hands the materials and implements for extraordinary operations.”

I

N MID

-J

ANUARY

1739, they returned to the countryside. Their destination was Cuenca, 100 miles distant, and to get there, they had to map their way through a mountain range that intersected the valley and crossed between the two cordilleras, like a rung on a ladder. In this region, known as the Azuays, they no longer enjoyed the clear lines of sight that had made it possible to bounce their way south from Quito, with signal points set up on mountains on each side of the plain. Instead, they had to triangulate their way

through terrain filled with “sandy moors, marshes and lakes,” and they had to do so during the rainy season.

As had been the case in the past, Jean Godin and Verguin went ahead to mark the triangulation points, and the others followed close behind. Everyone was battered as they struggled through this wilderness. La Condamine was robbed at one camp, thrown by his horse and injured at another, and rendered tentless by fierce winds at a third.

“I spent eight days wandering around the moors and marshes, without finding any shelter other than caverns in the rock,” he wrote. Bouguer suffered a grave fall in these mountains, and he complained that at night his

“sleep was continually interrupted by the roarings of the [Sangay] volcano,” a “noise that was so frightful.”

There were a few moments when the weather cleared and they enjoyed amazing vistas. To the north, the great Andean valley stretched out, with Mount Corazon visible 125 miles away. It was

“the most beautiful horizon that one can imagine seeing,” La Condamine enthused. And on March 24, they were treated to the spectacle of an eruption on Sangay.

“One whole side of the mountain seemed to be on fire, as was the mouth of the volcano itself,” La Condamine wrote. “A river of flaming sulfur and brimstone forged through the snow.”

But such moments were rare. Their work was hampered at every step by fog, rain, and sleet. In the final days of April, they were blasted by hail and snow. The raging winds destroyed three of their tents, their Indian servants deserted them once again, and they were forced to huddle together in a breach in the rocks. Twenty miles away, in the town of Cañar, a priest led a prayer vigil for them, the people of that town fearful that they “had all perished” in the horrible storm. All seemed hopelessly grim, until, a few days later, a messenger arrived at their newly established camp with a letter that offered some comic relief. Their colleagues in France, it seemed, were worried that with the expedition taking place so close to the equator, they might be

“suffering too much from the heat.”

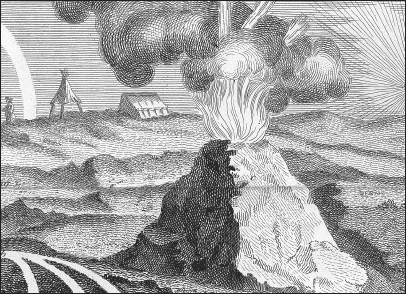

A volcano erupts.

From Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa

, Relación histórica del viage a la América Meridional

(1749), from the 1806 English translation

A Voyage to South America.

By mid-May, they had finally punched their way through the Azuays. The worst was now behind them, and with the terrain becoming gentler, they were able to rapidly make their way down to Cuenca. They arrived there in early June, and over the course of the next month, both groups, La Condamine’s and Godin’s, mapped the last of their triangles. La Condamine and Bouguer determined that they had measured off a meridian that was 176,950 toises long (214 miles). Godin and Juan had measured one that was slightly longer.

The final step in the triangulation process involved proofing their work. To do so, each group used a toise and wooden rods to measure the last side of their last triangle. This was known as a second baseline, and the logic of the proof was simple. Since this line was part of a known triangle, its length could be mathematically deduced. Physically measuring this distance would verify the calculated result. If the two were not equal, it would mean that unacceptable error had crept into their triangulation work, and much of it would have to be redone.

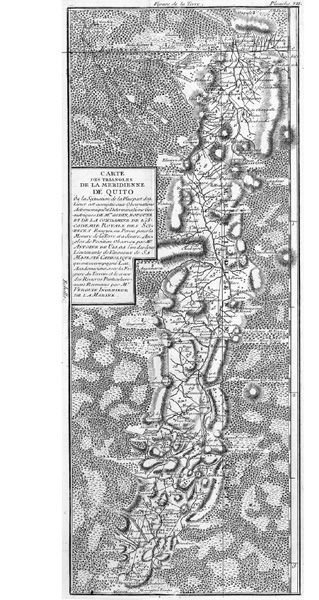

Bouguer’s map of the triangulation area in Peru.

By permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University

.

Each group had its own second baseline to measure. Although they had shared triangles part of the way, they had mapped out separate finishing triangles in the Cuenca region. Neither of the sites they had picked for this work was ideal. Godin and Juan had selected a plain that was bisected by a broad river; La Condamine, Bouguer, and Ulloa had chosen a spot a little further south, known as the plain of Tarqui, where they had to measure across a shallow pond one-half mile across. There they worked for days on end in the waist-deep water, tying the floating rods to stakes and then moving them forward in the same manner as on land.

As the men placed their final rods, they grew noticeably anxious. Two years of effort would be wasted if their results did not match up. They would have to retrace their steps and recheck all of their measured angles to find the source of the error. But both groups were able to breathe a sigh of relief: Their results were stunningly good. Godin and Juan determined that their baseline, as physically measured, was 6,196.3 toises long, which was only three-tenths of a toise—about two feet—less than its length as mathematically calculated. La Condamine and Bouguer achieved similar results. Their numbers for their second baseline—as measured and as mathematically calculated—differed by only two-tenths of a toise. The two groups had marked off meridian lines stretching more than 200 miles, through mountainous terrain and in miserable weather, and their proofs were accurate to within a couple of

feet

. At last, La Condamine wrote with understandable pride,

“our geometric measurements were completely finished.”

All they needed to do now was measure the height of a star from both ends of their measured meridians, and their work in Peru would be done. This would give them the difference in latitude of their meridians’ endpoints, and with this information in hand, they could precisely calculate the length of a degree of latitude at the

equator. Although they would need to build observatories, this would take six months at most. Their results put them in a festive mood, and so they retired to Cuenca, where they hoped to enjoy themselves for a few days before their final push. They would—or so they thought—be on their way home soon.

*

When Araujo’s investigation revealed that Alsedo had been one of La Condamine’s customers, Alsedo responded by accusing Araujo of selling contraband, a much worse offense. This set off a court battle between the two that dragged on for years. In many ways, the case typified the legal wrangling that strangled colonial Peru in the eighteenth century.