The Mapmaker's Wife (23 page)

Read The Mapmaker's Wife Online

Authors: Robert Whitaker

Tags: #History, #World, #Non-Fiction, #18th Century, #South America

From Charles-Marie de La Condamine

, Mesure des trois premiers degrés du méridien dans l’hémisphere austral

(1751)

.

In early October, both groups began making measurements, training their sights on a star in the Orion constellation. However, bad weather slowed their progress. Clouds obscured the night sky for weeks on end, and with Senièrgues’s murder so fresh in their minds, the constant rains cast a pall over the whole enterprise. It was a

“series of sad and difficult observations” they were trying to make, La Condamine wrote in his journal, and they were having to conduct them in a “lonely place.” By December, they were still not finished, and it seemed certain that 1739 would close with their spirits flagging. But their gloom was lifted by an unlikely group: Indians and mestizos holding a festival at Tarqui. The brightly costumed Indians, mounted on horseback, performed choreographed dances, and during an intermission, a group of mestizos put on a pantomime that, for the moment anyway, washed away their grief:

They had the talent of mimicking anything they saw and even things they did not understand. I had seen them observing us several

times while we took the measurements of the sun to adjust our pendulums. This must have been for them an impenetrable mystery to see a man on his knees at the base of a quadrant, head facing upwards in an uncomfortable position, holding a lens in one hand and with the other turning a screw on the foot of the instrument, and alternately carrying the lens to his eye and to the divisions to examine the plumb line and from time to time running to check the minutes and seconds on the pendulum and jotting some numbers down on a piece of paper and once again resuming the first position. None of our movements had escaped the observations of our spectators and when we least expected it they produced on stage large quadrants made of painted paper and cardboard which were rather good copies and we watched as each of us was mimicked mercilessly. This was done in such an amusing manner that I must admit to not having seen anything quite as pleasant during the years of our trip.

In early January, both groups completed their celestial observations in Cuenca. All they had to do now was perform similar observations in the plains north of Quito, and they would be done. After two long years in the mountains, they looked forward to the relative comforts of that city, where, they knew, friends like Pedro Gramesón would welcome them once again. Jean Godin in particular thought happily about returning to the Gramesóns. Indeed, he went to their home the minute he reached Quito, and he heard from the general this news: Isabel had turned twelve years old, the age when girls in Peru began to wed.

*

A plumb line is used to determine the point directly overhead. Gravity will cause a plumb line to point toward the earth’s center, and the extension of that line in the opposite direction identifies the point directly overhead.

T

HE LIFE COURSE THAT WAS PLOTTED

for upper-class girls in Peru sent them down one of two paths. After six or seven years of convent school, they were expected to “take a state.” Either a girl would prepare to marry a man, or, by becoming a nun, “marry God.” This moment of decision usually came at around age twelve, the age when Catholic doctrine deemed girls to be physically capable of intercourse. However, families who did not want to wait that long to arrange a favorable union for their daughters could obtain a dispensation from the church. Child brides nine and ten years old were not uncommon in colonial Peru.

Although Creoles and Spaniards wrangled endlessly in the political arena and often confessed their loathing for one another, the parents of a Creole daughter typically put aside such feelings when it came to marriage. A Spaniard was viewed as a superior choice. Everyone understood that Creole men did not have the same access to political power that Spaniards did, and Creole men, by and large, had a reputation for being lazy, spoiled, and vain.

“Creole women,”

Ulloa wrote, “recognize the disaster of marrying those of their own faction.” A Spanish groom would also be certain to have

limpieza sangre

(clean blood), and thus a white Creole family could be assured that the offspring of such a union would enjoy the many privileges that came with being white in colonial Peru. Those of pure Spanish blood were exempt from many colonial taxes and had a privileged claim on civil and ecclesiastical positions.

Most elite families would pick older men for their young daughters to marry. Six to twelve years of age difference was the norm. At times, however, a father would contract with a forty-year-old man to wed his twelve-year-old daughter, even though this was an age difference that the girls found loathsome. They would sing:

Don’t marry an old man

For his money

,

Money, money disappears

But the old man remains

.

However, Peruvian girls did want to marry, and at an early age. A girl who passed through puberty and turned twenty years old without marrying risked being thought of as an old maid, and rumors would likely fly that she was no longer a virgin, which would make it impossible for her to ever find a husband. And while elite families looked upon an arranged marriage as a business transaction, the girls naturally had their romantic fantasies. Courtly love was part of the same knightly tradition that prompted their seclusion.

The Amadís novels that were so popular in sixteenth-century Spain were, first and foremost,

romances

. Although the beautiful maiden may have been locked away in her castle, kept from the world by bars on her windows, such sequestration was necessary precisely because she pined so for her knight, and did so in a feverishly physical way. These books, lamented one sixteenth-century bishop,

“stir up immoral and lascivious desire.” Yet another priest lamented that “often a mother leaves her daughter shut up in the

house thinking that she is left in seclusion, but the daughter is really reading books like these and hence it would be far better for the mother to take the daughter along with her.” Indeed, Spanish girls devoured the books. Saint Teresa de Jesus of Ávila confessed in her autobiography that as a child she had been

“so utterly absorbed in reading them that if I did not have a new book to read, I did not feel that I could be happy.”

In Peru, this vision of romance found a real-world outlet in the amorous liaisons between men of Spanish blood and lower-caste women. As seventeenth-century visitors noted in their travelogues, Spanish men in Peru thought of mulattos and mestizos as their “women of love.” The woman who was the object of such affection was a recognized type in Peruvian society, known as a

tapada

. She was, American historian Luis Martín has noted, the “sex symbol of colonial Peru.”

She was always dressed in the latest fashions, and her clothing was made of the most expensive, imported materials. She favored lace from the Low Countries, exquisite silks from China, and exotic perfumes and jewelry from the Orient. The length of her gown was shortened several inches to reveal the lace trim of her undergarments, and to draw attention to her small feet covered with embroidered velvet slippers.

While upper-class girls in the convent schools were taught to assume a different role, to be honorable and chaste in their thoughts, they still were greatly influenced by this culture. Rare was the Peruvian girl, one historian wrote, who did not fancy sneaking away at night for

“an amatory conversation through the Venetian blinds of the window of the ground floor.” The girls’ seclusion, which allowed their imaginations to run rampant, only reinforced this feeling. Their “frantic desire to marry,” a Peruvian scholar noted, was “aggravated still more by the ban on speaking to men, except cousins.” Moreover, even in the convents, there was an ever-present undercurrent of sexuality. All of the girls would giggle

in private over the nicknames that locals gave to the pastries and candies that the nuns produced and sold—the sweets were known as

“little kisses,” “raise-the-old-man,” “maiden’s tongue,” and “love’s caresses.”

As Isabel reached this moment in her life, she was by all accounts quite fetching. Petite and with delicate features, she had the slender fingers and tiny feet that men in colonial Peru so fancied. While she had the usual dark hair of the Spanish, her skin was milk-white, and in this regard, she looked very much a daughter of Guayaquil, for the women of that port city were known to be “very fair” in complexion. Those who knew her spoke of her “good soul” and of how “very pretty” she was, and of her obvious intelligence. She could speak both French and Quechua, having learned this latter language as a child, when she had had an Indian wet nurse. Even La Condamine, usually so discrete in his comments, pronounced her “delicious” upon meeting her, and remarked that she had a “provocative” mouth. He was, in the manner of the times, simply stating what everyone saw: Isabel Gramesón, who was both pretty and from a prosperous family, was going to be quite the catch.

T

HE

F

RENCH ACADEMICIANS

finished their astronomical observations around Quito in April 1740, prompting La Condamine to triumphantly declare their work complete.

“After four years of a traveling life, two of which had been spent on mountains, we were ready to calculate the degree of the meridian which was the purpose of so many operations.” Yet even at this apparent moment of success, they were gnawed by doubt. Their measurements of stars in the Orion constellation had consistently varied “8 to 10 seconds” from one night to the next. Although this was a small discrepancy, it still prevented them from feeling secure about the precision of their work. They had not quite reached the ambitious goal that they had set for themselves, and as they mulled over this problem, they concluded that the fault must lie with their zenith sectors. If the long telescope flexed by so much as one-sixth

of an inch between viewings, a star’s apparent position would shift by twenty seconds. Everyone glumly realized what they must do: Hugo would have to make the instruments more stable or build new sectors altogether, and then they would have to repeat their celestial observations.

While waiting for Hugo to do his work, the others busied themselves in various ways. La Condamine, for his part, returned to Cuenca, intent on bringing Senièrgues’s killers to justice. He wrote to the viceroys in both Lima and Santa Fe de Bogotá,

*

collected statements from witnesses to the murder, and even mounted a legal case against the priest whose sermons had helped spark the riot.

“I love my country,” La Condamine wrote in his journal. “I believe that I have an obligation to defend the honor and interests of my sovereign, of my nation, and of my academy.” That case seemed to stoke his appetite for other legal battles as well. La Condamine sued three individuals who had not returned goods he had loaned them, and then he got into an argument with Ulloa and Juan that also headed to court.

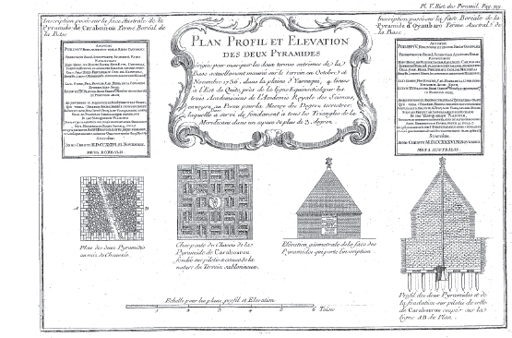

The dispute with Ulloa and Juan was over how the French planned to commemorate the expedition’s work. Even before they departed from France, they had decided to build monuments at the ends of their first baseline. This had been thought out in such detail that the academy had written the inscription that was to be used. La Condamine had taken charge of this task, and he had decided to build pyramids, rather grand in size—twelve feet by twelve feet at the base and fifteen feet tall—to mark their Yaruqui baseline. There was a scientific rationale for putting up markers, as it would enable other geodesists to check their work. But the pyramids would also serve to glorify those who performed the deed, and therein was the problem: La Condamine, as he fiddled with the

wording of the inscription prepared by the academy, sought to describe the two Spanish naval officers as “assistants.”