The Mapmaker's Wife (17 page)

Read The Mapmaker's Wife Online

Authors: Robert Whitaker

Tags: #History, #World, #Non-Fiction, #18th Century, #South America

A panoramic view of the plain of Yaruqui.

From Charles-Marie de La Condamine

, Journal du voyage fait par ordre du roi à l’équateur

(1751)

.

T

HROUGHOUT THIS PERIOD

, everyone in Quito was keeping up with the progress of the French expedition, even though they were not quite sure what the visitors were up to. Their presence even stirred a passing fancy for things French. Ever since Spain had come under the rule of a Bourbon king, the elite in Quito, influenced by a steady stream of Crown-appointed administrators who came to the town, had come to think of French customs as superior to their own, and now, with the French scientists nearby, the wealthy residents of Quito could more easily imagine being part of that elegant world. The women practiced their curtsies and memorized a few French phrases, and, according to one account of the times, no party was complete unless the host could provide a bottle of French wine.

Pedro Gramesón and his family became personally acquainted with the French mapmakers. The general spoke passable French, having learned it from his father, and his house, one Ecuadorian historian has noted,

“was always open for all the French men.” In fact, he could boast that his brother-in-law had played a small role in making the expedition happen. When the French had first proposed it to King Philip V, Spain’s Council of the Indies, which oversaw all colonial matters, had sought advice from several notables in Peru, one of whom was José Augustín Pardo de Figueroa, the Marqués de Valleumbroso. Pardo had a keen interest in science, and he had given his whole-hearted approval. He particularly liked the idea that two Spaniards would be assigned to this expedition, although not because they would keep tabs on the French. Instead, he saw their presence as a way that Spain could participate in this endeavor and learn

“the practice of astronomy and trigonometry.” After the academicians had arrived, Pardo and La Condamine had quickly become friends, La Condamine writing in his diary of how impressed he was “by his [Pardo’s] knowledge and how well read he was.” There were other ties as well that brought the Gramesóns closer to the expedition. The Gramesóns and Jean Godin’s family

shared mutual close friends, the Pelletiers from Lignieres, a village near Saint Amand. Members of the Pelletier clan living in Cadiz, Spain, shared business interests with the Gramesóns there, while in France the Pelletiers and the Godins had known each other for at least three generations. The connection may have been a distant one, but it made Jean Godin feel welcome at the Gramesóns, and he became a regular guest.

Although Isabel was still in a convent school, she heard all about the French men from her father and through other gossip that filtered into the cloister. The school had not turned out to be such a dismal place. She and the other girls had learned to read and write, and they all enjoyed singing in the choir. Occasionally, the nuns even hosted small fiestas, having musicians and singers in to entertain. And every day, visitors were allowed into the convent parlor to call on the girls, enabling them to keep up with all that went on in Quito. Often they wondered whether it was true, as had been whispered, that the French men had shown the women of Quito a Parisian dance step or two. That was a deliciously scandalous thought, and it naturally caught Isabel’s fancy. She had particular reason to be fascinated by this world—her grandfather, after all, was French, and her family personally knew the scientists—and this interest was starting to blossom into an unusual ambition for a Peruvian girl. She had yet to turn nine years old, but—as would later become evident—she had already begun to dream of one day seeing France for herself.

*

A plumb line points to the center of the earth, and thus the French academicians could move their sawhorses up or down along a vertical axis.

W

ITH THE BASELINE MEASURED

, the French academicians thought that they could complete their mission within eighteen months. Bouguer was even more optimistic. He believed that they might finish by the end of 1737, and he wrote to his colleagues in Paris that he now had “hope of seeing France once more.” But in January of 1737, the French academicians began to realize that they were being overly optimistic, their efforts certain to be delayed by a lack of money, the upside-down world of colonial politics, and their own internal squabbling.

Although it was now twenty months since they had left La Rochelle, they had yet to receive any letters from France. Nearly everyone had sold personal goods to keep the expedition going—even a telescope had been peddled—but in the absence of any new letter of credit, they were, as a group, once again nearly broke. The Peruvian viceroy, the Marqués de Villagarcía, had denied Louis Godin’s request for an advance beyond the 4,000 pesos already given to the expedition. To further complicate matters, Alsedo was

no longer the president of the Quito Audiencia. He had been replaced on December 28, 1736, by Joseph de Araujo y Río, a small-minded man who immediately began harassing the French academicians and the two Spanish officers accompanying them. Without any money or political support in Quito, La Condamine decided to travel to Lima, 1,200 miles distant, in order to make a personal appeal to the viceroy. If that failed, he hoped to cash a personal letter of credit that he had brought with him from a French businessman in Paris.

La Condamine left Quito on January 19, 1737, and on his way to Lima, he stopped in Loja to investigate the famous cinchona tree that grew nearby in the tropical rain forest, on the eastern slopes of the Andes. The bark of this tree was in great demand in Europe as a treatment for fever, particularly when the fever was accompanied by terrible sweats and chills (an illness soon to be named malaria.) It was sold there as “Jesuits’ bark” or as “the countess’s powder,” the latter name arising from a story that Francisca Henriquez de Ribera, the Condesa de Chinchón, wife of a Peruvian viceroy, had been miraculously cured of a high fever by a preparation from this tree in 1638. Indians in the Loja area referred to it as

quina quina

(the bark of barks), and on February 3, La Condamine spent a night with a

cascarillero

, an Indian skilled in stripping the bark from the trees.

The opportunity to learn more about this tree could easily have justified an entire expedition. While a dose of the countess’s powder often worked wonders, the preparations varied widely in their efficacy. The problem was that there were many species of cinchona, and not all had the same therapeutic value. The Indians of Peru used the same name,

quina quina

, to describe a balsam tree, and its bark, which regularly showed up in European apothecaries, was worthless. Old World merchants and pharmacists were eager to know how to separate the good from the bad, and La Condamine, after his three-day stay in Loja, wrote a scientific treatise, “Sur l’arbre du quinquina,” on the tree, complete with a drawing of its leaves. He noted that the inner bark came in three colors,

white, yellow, and red, and the red one, which was more bitter than the others, appeared to be the most potent against fevers. No one had ever published a detailed botanical description of cinchona, and when the treatise was published by the French Academy of Sciences in 1738, it caused a sensation.

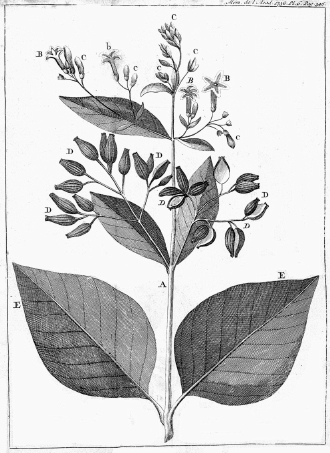

La Condamine’s sketch of

Cinchona officinalis

.

The Wellcome Trust Medical Photographic Library

.

La Condamine arrived in Lima on February 28, only to find that it was an inopportune time to be seeking a loan. Funds were scarce in the capital. Nearly all of the gold and silver from the mines had recently been loaded on a frigate for shipment to Spain. Even if the viceroy had been willing to lend the expedition money, there was little in the royal coffers. Three weeks later, La Condamine received more bad news: The new president of the Quito Audiencia, Araujo, had filed criminal contraband charges against him and sought his arrest. Authorities in Lima searched his belongings thoroughly, and while nothing illegal was found in his possession, his motives were now seen as suspect. All of Lima was

buzzing over this scandal when Juan unexpectedly showed up in the capital, with an even more salacious tale involving the new president.

The viceroy’s appointment of Araujo had been unusual, for Araujo was a Creole, a native son of Lima. The relationship between Creoles and

chapetones

, as those born in Spain were called in Peru, was contentious throughout the viceroyalty, and particularly so in Quito, which was known for being thoroughly dominated by the chapetones. The Creoles disliked the chapetones for their superior airs, and they had been quick to make fun of Ulloa and Juan, too, referring to them as the

caballeros del punto fijo

(knights of the exact)—men who preferred the pencil to the sword, a put-down that nobody could miss. But the disdain was mutual. The chapetones complained that the Creoles were spoiled and lazy, living off the labor of slaves and Indians and devoting all their energies to frivolous affairs. They have

“no employment or calling to occupy their thoughts, nor any idea of intellectual entertainment,” Ulloa and Juan observed. Instead, they said, the Creoles spent most of their time drinking, gambling, and going to “balls and entertainments.” Alsedo, during his term as president, had exacerbated the bad feelings between the two groups by excluding Creoles from the local cabildo, and when Araujo had replaced him, the Creoles had danced with joy, eager to see the tables turned.

Araujo did not disappoint them. Even though he himself had arrived with a mule train of goods to sell in Quito, which was forbidden, he immediately launched an investigation into La Condamine’s contraband activities, confident that it would embarrass Alsedo.

*

He also found a way to needle Ulloa and Juan, repeatedly addressing them with

usted

, the common form for “you,” instead of the more formal

usía

. Given the diplomatic protocol of

the day, this was the rankest kind of insult. Ulloa and Juan were members of the Guardias Marinas, in Peru as representatives of the king, and, just as Araujo had hoped, they were outraged. A Creole was acting as

their

superior, and doing so in public for all of Quito to hear? When Araujo ignored several admonishments to stop, Ulloa reached his breaking point. He charged into the president’s house one morning, brushed aside servants who tried to stop him, and confronted Araujo in his bedroom.

Usted?

He told off the president with a few choice words of his own, then turned on his heel and left, returning home—as a biographer later wrote—a much “happier man.”

Naturally, Araujo escalated the battle. He sent out armed officers to arrest Ulloa and Juan. The two Spaniards, however, refused to be taken into custody and instead drew their swords, badly wounding one of Araujo’s men before fleeing to the Jesuit church where La Condamine had holed up the previous summer. Enraged, Araujo ordered his men to surround the church. He swore he would starve them out, by God, and he promised bystanders that if the two cowards dared to show their faces, he would have them killed. All of Quito found this a spectacle not to be missed, but the show ended a few nights later when Juan slipped out under the cover of darkness and hurried to Lima to seek relief from the viceroy, whom he had befriended on his trip across the Atlantic.