The Mapmaker's Wife (19 page)

Read The Mapmaker's Wife Online

Authors: Robert Whitaker

Tags: #History, #World, #Non-Fiction, #18th Century, #South America

The problems they encountered were numerous, and one that slowed both groups was that they could not keep intact the wooden pyramids they were using as markers. Each pyramid was covered with a light-colored cloth to make it more visible, and to work, the academicians would set up a quadrant atop this pavilion, sighting through the instrument’s telescope similar markers off in the distance. But when the pyramids were not being “carried away by tempests,” Bouguer reported, they were being taken by Indians, who had other uses for the timber and ropes. Jean Godin was not always able to watch over the pyramids until the others arrived, and even when the main party arrived at a camp, the local Indians were apt to creep in at night and grab what they could. After La Condamine and Bouguer rebuilt one of their stations seven times, they grew so frustrated that they decided to start using the smaller tents as markers.

“Mr. Godin des Odonais preceded us,” La Condamine wrote, “and had these [tents] placed on the two mountain ranges, at designated points, according to the agreed location of the triangles, leaving an Indian to guard them.” While this procedure

worked better than erecting the pyramids, the tents also disappeared more than once, stirring the academicians to lash out in their journals against the Indians, whom they disparaged, in the manner of the times, as slovenly “beasts.”

A field camp in the Andes.

From Charles-Marie de La Condamine

, Mesure des trois premiers degrés du méridien dans l’hémisphere austral

(1751)

.

With every camp they set up, they had new mishaps and close calls to write about. As they worked on the slopes of towering Mount Cotopaxi, Juan fell into a twenty-five-foot-deep ravine with his mule, luckily escaping with only a few cuts and bruises. Bouguer regularly complained about the nasty conditions, and La Condamine, while riding between two camps, was caught in a fierce storm and had to spend two days in a snow-covered tent without food or water. At last, he used the lens of his glasses to focus the sun’s rays on a pot of snow, which provided a few drops of water that saved him

“from this sad situation.”

Despite these hardships, the team members explored their world in every way imaginable. They did not limit themselves to their triangulation work, difficult as it may have been. Through their experiments with a pendulum clock, they discovered—just as Newton had predicted—that the earth’s gravitational pull weakened with altitude. They needed to make the seconds pendulum about one-twenty-fourth of an inch shorter at an altitude of 10,000

feet than it was at sea level, which led La Condamine and Bouguer to calculate that a body that weighed 1,000 pounds at the seashore would weigh one pound less atop Pichincha. They also dragged a barometer to the top of Mount Corazon, a volcano 200 feet higher than Pichincha. Atop the summit, their

“clothes, eyebrows and beards covered in icicles,” they figured that no humans had ever “climbed a greater height.” They “were at 2,470 toises [15,794 feet] above sea level,” La Condamine wrote,

“and we could guarantee the accuracy of this measurement to four or five toises.”

*

Their experiments with the barometer were paying off, as Bouguer had come up with a “very simple rule” for using barometric pressure to calculate altitude. Air pressures at higher elevations, he had concluded,

“alter in a geometrical progression, while the heights of places are in arithmetical progression.” His method for determining the height of a mountain involved taking a reading at its base and at its summit, and then applying the logarithmic rule he had devised.

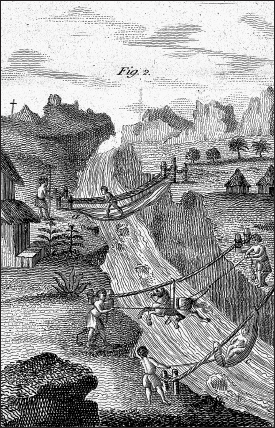

The French scientists were men of the Enlightenment at play. They investigated the climate of the Andes, the expansion of metals in response to variation in temperature, the speed of sound at high altitudes, the rocks and plants, and Inca ruins. Ulloa, meanwhile, was fascinated by some of the clever methods the Indians had devised for navigating this landscape. The road south of Quito regularly crossed ravines several hundred feet deep, and at several of these the Indians had built a “cable car” of sorts, known as a

tarabita

. Men and animals alike were winched across the ravine, riding in a leather sling attached to the cable, which was a rope made from twisted strands of leather. One such tarabita they came upon was strung at a height of more than 150 feet, the river below charging through a boulder-strewn gully.

As might be expected, all of this activity stirred a great deal of gossip among the locals. The behavior of these visitors was so

strange

. They climbed to absurd heights on the mountains, peered into odd-looking instruments, and furiously scribbled away in their notebooks. Their three-week stay atop Pichincha had earned them the reputation of being “extraordinary men,” La Condamine noted, and there were whispers among some of the Indians that these strangers were superior beings, shamans of a sort. At a camp near Latacunga, a group of four men even got down on their knees to pray to them. Could they use their powers to help them locate a lost mule? When Ulloa told them they had no such knowledge, the Indians refused to believe him.

“They retired with all the marks of extreme sorrow that we would not condescend to inform them where they might find the ass, and with a firm persuasion that our refusal proceeded from ill nature, and not from ignorance.” Others, Ulloa added, were convinced that they were prospectors looking for gold. Wasn’t Mount Pichincha rich in minerals? Hadn’t Atahualpa buried his treasure there? And wasn’t that the reason that everyone came to this land, to get rich?

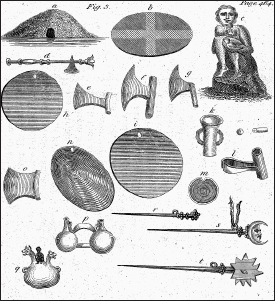

Inca artifacts.

From Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa

, Relación histórica del viage a la América Meridional

(1749), from the 1806 English translation

A Voyage to South America.

Bridges in eighteenth-century Peru.

From Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa

, Relación histórica del viage a la América Meridional

(1749), from the 1806 English translation

A Voyage to South America.

Even those of the best parts and education among them were utterly at a loss what to think. … Some considered us little better than lunatics, others more sagaciously imputed the whole to covetousness, and [said] that we were certainly endeavoring to discover some rich minerals by particular methods of our own invention; others again suspected that we dealt in magic, but all were involved in a labyrinth of confusion with regard to the nature of our design. And the more they reflected on it, the greater was their perplexity, being unable to discover any thing proportionate to the pains and hardship we underwent.

Indeed, as the months passed, the physical hardships began to wear the men down. They moved steadily from one camp to another, their daily lives, Ulloa noted, marked by “continual solitude and coarse provisions.” Their only respite from this difficult life came when they were passing between camps, when they might have time to spend a day in a little town, everyone so starved for the

comforts of civilization that

“the little cabins of the Indians were to us like spacious palaces, and the conversation of a priest, and two or three of his companions, charmed us like the banquet of Xenophon.” Loneliness was now creeping into their writings, and by mid-October it was clear they needed a respite. Ulloa fell gravely ill and had to be taken to the nearby city of Riobamba. Louis Godin suffered a similar bout of sickness and returned to Quito to recuperate. The expedition was once again short of funds, supplies were low, and Riobamba, a city of 16,000, offered them a civilized place to rest. They had also recently received a cache of letters from France that had delivered an emotional blow and left them wondering how to proceed.

T

HE DIFFICULTY IN CORRESPONDING

with colleagues in France had led La Condamine, at one point, to complain that he had nearly given up on ever hearing from Paris. The first letter the expedition received arrived in late 1737, shortly after they had come down from Pichincha. In it, Maurepas—the minister who had promoted their expedition to the king—had sought to resolve the ongoing dispute between Godin and Bouguer over the merits of measuring a degree of longitude. Each of the academicians had written Paris to argue his case, and the academy, Maurepas wrote, had agreed with Bouguer’s opinion that it would be a

“completely imprudent enterprise.” While Godin had not immediately given up on the idea, his own subsequent experiments on the speed of sound, which he had completed in July 1738, supported the academy’s decision. Godin had determined that sound at this altitude traveled between 175 and 178 toises a second, but that imprecision—of three toises per second—was too great to allow them to use a sound, such as the noise of a cannon being fired, to synchronize watches at two spots along a line measured at the equator. The margin of error would be greater than any difference in distance between degrees of longitude and latitude at the equator, Bouguer noted, and thus

“one might even come to believe that the

earth is flattened or oblong when in fact it may have a completely different shape.”

So that issue had been resolved, but now, as a result of letters they had just received, they had to question the merits of proceeding even with their latitude measurements. Maupertuis, they had learned, had already returned with his results from Lapland.

The Maupertuis expedition had not lacked its own controversies. Maupertuis was a committed Newtonian, as were the other leaders of the expedition, such as Alexis Clairaut. As a result, many in the academy were ready to dismiss their results even before they left, certain that Maupertuis and Clairaut were too biased to do the work fairly.

“Do the observers have some predilection for one or the other of these ideas?” asked Johann Bernoulli, the Belgian mathematician who was a supporter of the Cassinis. “Because if they believe that the Earth is flattened at the poles, they will surely find it so flattened. … [T]herefore I shall await steadfastly the results of the American observations.” Despite such skepticism, Maupertuis and six others had gone to Lapland in April 1736 and returned seventeen months later with an answer. They had determined that a degree of latitude in Lapland was 57,437 toises, which was 477 toises longer than a Parisian arc, as measured by the Cassinis in 1718. Thus, Maupertuis told the academy,

“it is evident that the earth is considerably flattened at the poles.” Newtonians naturally pounced on this news, Voltaire gleefully praising Maupertuis as the

“flattener of the earth and the Cassinis.”

But as Bernoulli had predicted, the Lapland results did not end the dispute. Many of the old guard in the academy were outraged, Jacques Cassini complaining that Maupertuis was trying to destroy in one year the work his family had taken fifty years to create. He and others criticized Maupertuis’s work as sloppy and snidely suggested that the expedition members had all taken mistresses in Lapland, evidence that they were moral degenerates. Maupertuis was so disheartened that he hurried away to Germany, where he became president of the Berlin Academy of Sciences.

“The arguments

increased,” he wrote bitterly, “and from these disputes there soon arose injustices and enmity.”