The Mapmaker's Wife (12 page)

Read The Mapmaker's Wife Online

Authors: Robert Whitaker

Tags: #History, #World, #Non-Fiction, #18th Century, #South America

The bay of Cartagena had been discovered by Spaniards in 1502, and its geography made it ideal for a military port. From the sea, ships could reach the city only by sailing through a narrow straight, which in 1735 was guarded by two forts. Even so, pirates and other foreigners had attacked Cartagena numerous times in its 200-year history. Its worst moment had come in 1586, Ulloa and Juan noted, when the Englishman Sir Francis Drake had set the town on fire and extracted a ransom of 120,000 silver ducats from its inhabitants.

As was the Spanish custom, the streets of Cartagena were laid out in a grid, with a

plaza mayor

in the center, where the administrative buildings, including the Court of the Inquisition, could be found. Well-to-do whites lived in fine houses with wooden balconies, and their homes, Ulloa and Juan observed, were “splendidly furnished.” During the midday heat, the women of these homes

could usually be found “sitting in their hammocks and swinging themselves for air,” and everyone, men and women, stopped for a brandy each morning at eleven. Nature and commerce provided a daily feast for their dinner tables. The wealthy of Cartagena dined on rice, grains, fish, meats from animals of every kind—cows, hogs, geese, deer, and rabbits—and a cornucopia of New World fruits, such as pineapples, guavas, papayas, guanabanas, and zapotes. Chocolates filled their cravings for sweets, and nearly everyone, including the women, enjoyed a good smoke.

But these pleasures were reserved for the well-to-do. The other inhabitants of Cartagena, Ulloa and Juan noted, “are indigent, and reduced to mean and hard labour for subsistence.” There was a leper colony in the town, and many of the poor—mostly mestizos and freed Negroes—resided in miserable straw huts, where they lived “little different from beasts, cultivating, in a very small spot, such vegetables as are at hand, and subsisting on the sale of them.” The street markets where such produce was sold had a distinct African tone, the Negro women wearing “only a small piece of cotton stuff about their waist” and caring for their infants in a way that amazed the two Spaniards:

Those who have children sucking at their breast, which is the case of the generality, carry them on their shoulders, in order to have their arms at liberty; and when the infants are hungry, they give them the breast either under the arm or over the shoulders, without taking them from their backs. This will perhaps appear incredible; but their breasts, being left to grow without any pressure on them, often hang down to their very waist, and are not therefore difficult to turn over their shoulders for the convenience of the infant.

As was true throughout Peru, the bringing together of three races—whites, Negroes, and indigenous groups—had produced a multihued population in Cartagena, and the colonial city went to great lengths to identify the amount of “impure blood,” whether

black or Indian, that tainted those who were not 100 percent white. The result was a very complicated caste system. When a white mated with a Negro, Ulloa and Juan reported, the child was deemed a mulatto, and it took several generations of marrying back into white families for the mulatto blood to be washed out. The offspring of a mulatto and a white was deemed to be a

terceron

, and if a terceron married a white, their children were considered

quarterones

. A mix of quarteron and white produced a

quinteron

, and the child of a quinteron and a white was considered to have made it all the way back to being a “Spaniard, free from all taint of the Negro race.” When a Negro married an Indian, their offspring were known as

sambos

, and when a quarteron married a terceron or a mulatto, their children were called

salto atras

, or “retrogrades, because, instead of advancing towards being whites, they have gone backwards towards the Negro race.” This was a racial ladder of many steps, and everyone knew where he or she stood on it, “so jealous of the order of their tribe or cast that if, through inadvertence, you call them by a degree lower than what they actually are,

they are highly offended, never suffering themselves to be deprived of so valuable a gift of fortune.”

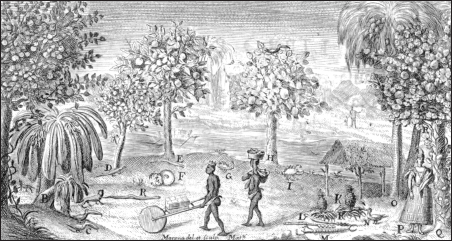

Daily life in Cartagena.

From Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa

, Relación histórica del viage a la América Meridional

(1749)

.

Ulloa and Juan observed the wildlife of Cartagena with equal diligence. There were tigers, foxes, armadillos, lizards, monkeys, and colorful snakes to be described. At dusk, vampire bats flew in such great numbers that they covered the sky and made their way into homes, where “if they happen to find the foot of any one bare, they insinuate their tooth into a vein, with all the art of the most expert surgeon, sucking the blood till they are satiated.” The two Spaniards identified “four principle kinds” of mosquitoes that tormented the inhabitants of Cartagena, described the life cycle of a parasitic worm called the

cobrilla

that was about the “size of a coarse sewing thread,” and dwelled at great length upon the

nigua

, a flea that would pester them for the rest of their days in Peru. This insect liked to bury itself in “the legs, the soles of the feet or toes” and make its nest there, depositing its eggs and eating the host’s flesh for sustenance, all of which caused a “fiery itching.” Removing the insect and its nest often caused extreme pain, because sometimes “they penetrate even to the bone, and the pain, even after the foot is cleared of them, lasts till the flesh has filled up the cavities they had made.” To ward off infection, the wounds were “filled either with tobacco ashes, chewed tobacco, or snuff.”

Cartagena was only the first stop on their journey, but already Ulloa and Juan were proving to be keen observers and able writers, busily compiling notes for the first chapter of a travelogue that would, upon its publication in 1748, become a best-seller throughout Europe.

I

T WAS NOT UNTIL

early November that the French academicians obtained permission to depart for Cartagena. The governor of Santo Domingo, unable to provide them with a ship, at last allowed them to sail in a French vessel, the

Vautour

, captained by a Mr. Hericourt. On November 16, the two groups finally met, and while the French were initially a bit resentful of this intrusion into their

expedition, the friendliness of the two Spaniards quickly put everyone at ease, La Condamine remarking that

“the knowledge and the personal merit of these two officers showed the high level of the guards of the Spanish Navy.” With everyone together now, they debated the best way to proceed. Several in the group favored heading overland to Quito, a journey that would involve poling up the Magdalena River for 400 miles and then proceeding on mules through the Andes for another 500 miles. “Ordinary travelers” took nearly four months to make this trek, and La Condamine was adamantly opposed to this route. Their equipment and delicate instruments would all have to be repacked, and with the large amount of baggage they carried, the journey could be expected to take much longer than usual. All this, he said, would cause

“great fatigue, time and expense.” The forceful La Condamine won this argument—indeed, he rarely lost such battles—and on November 24, they all boarded the

Vautour

for Porto Bello, where they would disembark in order to cross the Isthmus of Panama. Their group numbered twenty-six: Ulloa and Juan had two servants and the French now had twelve, the governor of Saint Domingue having provided them with five or six slaves.

Porto Bello was well known throughout the Spanish Empire as a dreadful place to visit. It was a hub for the Peruvian export trade, the market open forty days each year. All of the goods exported from Quito and points south in Peru came through this port, having been shipped up along the Pacific coast to Panama City and then packed across the isthmus by mule. The mule train would reach Porto Bello at the same time as a convoy of trading ships from Spain, the

Galeones

, arrived bearing luxury items to be imported into Peru. Tents filled with merchandise crowded the

plaza mayor

and slaves were sold; with so many traders in town, rent for a single house for the six weeks could fetch

“four, five, six thousand crowns,” Ulloa and Juan reported. But the swampy port was also a hotbed of disease. Low mountains surrounded the town, blocking winds that might have refreshed the air or blown away the mosquitoes, and rain pounded down incessantly. The illness of

Siam and “fever,” soon to become identified as malaria, often claimed the lives of half the crew of a visiting ship, earning Porto Bello the nickname “the tomb of Spaniards.”

As the

Vautour

neared the port on November 29, it encountered a storm that stirred all their misgivings. Gale winds tossed the ship about so fiercely that it was unable to enter the harbor, and the men had to wait until the following day to go ashore. Jussieu arrived with a fever, and several others fell sick during the next several days. Local bureaucrats also took to heart King Philip’s order that their baggage be closely inventoried.

“These verifications were so precise,” La Condamine complained, “that we were unable to prevent the customs officials from discovering a metal mirror which formed part of a catoptrical telescope, which we feared the humidity in the air of Porto Bello might damage.” A scorpion’s sting deepened La Condamine’s foul mood. He treated the bite with a poultice of his own making, which, he reported, relieved the pain so well that it could replace “all of the ridiculous and disgusting remedies used in the country.”

The men were stranded in Porto Bello for nearly a month. The route across the isthmus to Panama City had been made impassable by rain—La Condamine called it “the worst road in the world.” Their only alternative was to travel up the Chagres River, and that required waiting for the governor of Panama to send them river-boats. They spent the time doing what experiments and good deeds they could. After Jussieu recovered from his fever, he provided medical care to the local populace; Godin and Bouguer measured the length of the seconds pendulum; and Ulloa, Juan, and Verguin mapped the town. But most days were gray and damp, so gloomy that even the two Spaniards concluded that the town was

“cursed by nature.” The incessant croaking of frogs kept them awake all night, and in the morning, if it had rained, the streets would be so blanketed with toads that the men could barely walk

“without treading on them.”

The vessels that arrived for them on December 22 were flat-bottomed barges known as

chatas

. Each had a cabin at its stern for

the comfort of passengers, and a crew of “eighteen to twenty robust Negroes” manning the oars. The forty-three-mile trip up the Chagres turned out to be an unexpected joy. For the first two days, the flow of the river was such that they could proceed by rowing, but then the river’s speed quickened and its depth lessened, so they poled their way along. The surrounding wilderness, Ulloa wrote, was so glorious that

“the most fertile imagination of a painter can never equal the magnificence of the rural landscapes here drawn by the pencil of Nature.” Alligators sunned themselves on the riverbank, turtles floated by on drifting tree limbs, and everywhere they looked they could see the colorful plumage of peacocks, turtle-doves, and herons. Monkeys diverse in size and color swung from every tree, and each night, the boat’s crew would gather food from the forest for their supper, plucking pineapples from trees and hunting pheasants and peacocks. Monkey was also served, and this meal, Ulloa confessed, initially made some of the group uneasy:

When dead, [the monkeys] are scalded in order to take off the hair, whence the skin is contracted by the heat, and when thoroughly cleaned, looks perfectly white, and very greatly resembles a child of about two or three years of age, when crying. This resemblance is shocking to humanity, yet the scarcity of food in many parts of America renders the flesh of these creatures valuable, and not only the Negroes, but the Creoles and Europeans themselves, make no scruple of eating it.

As they ascended the Chagres, La Condamine mapped its winding route, and Jussieu, at every possible occasion, urged them to stop so that he could gather plant specimens. It took them five days to reach Cruces, a small village at the head of the river, and from there it was a short fifteen miles by mule to Panama City, where they arrived late in the afternoon on December 29. Here they spent the next seven weeks making arrangements for a boat to take them south to Peru, and except for the fact that La Condamine, Bouguer, and Godin continued to quarrel over money and plans for measuring

the arc, the respite was welcome. All of the French members of the expedition studied Spanish, and the three academics performed various investigations

“of the thermometer, the barometer, and variations of the magnetic needle,” La Condamine reported. Jussieu explored the local vegetation, going out alone on walks each day with a bag on his back to gather botanical specimens.

“I see that this trip,” he wrote in a letter to his brothers on February 15, 1736, “which shall after all have but one (stated) purpose, will in fact collect knowledge of geographic, historical, mathematical, astronomical, botanical, medicinal, surgical and anatomical subjects, etc. As we go along we collect instructive reports, which shall make up a comprehensive and fascinating body of work.”