The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (13 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

Honorius refused, and Alaric fulfilled his threat, marching straight back to Rome. This time the siege dragged on a little longer, until Rome was hungry, exhausted, and beginning to suffer from plague. Alaric refused to leave, promising that he would see the city starve to death unless he was given a place to settle.

No help came from Honorius, safely holed up in Ravenna. He had already received a message from the Roman soldiers left in Britannia after Constantine III’s departure, begging for relief, and had sent them back a curt order to cope on their own. He had no soldiers to send either to Britannia or to Rome.

So the Roman Senate offered Alaric a deal. The Roman people would never accept Alaric as emperor, but the Senate would declare one of its own, the senior senator Attalus, to be emperor in place of Honorius. Alaric could then become his

magister militum

, his top military official; like Stilicho before him, he would become ruler in all but name.

To seal the deal, the Visigoths and the senators exchanged hostages, a strategy meant to ensure that each side kept its bargain for fear of its hostages losing their lives. One of the hostages sent by the Romans was a fourteen-year-old boy named Aetius, the son of a high Roman official; he would grow to adulthood among the Visigoths.

15

Now there were three emperors in the west: Honorius in Ravenna, Attalus in Rome, and Constantine III in Gaul. Not long after, a Roman official in Hispania declared himself to be an emperor as well. Any hope that Christian faith would bind the whole disintegrating mess together had entirely disappeared. Conquest was the only hope that any of the four emperors had of reunifying the western empire.

Very soon, the cardboard emperor Attalus and his

magister militum

Alaric fell out with each other. When the Senate suggested putting a joint army of Visigoths and Romans under the command of a Visigoth officer, Attalus refused indignantly. He argued that putting a Visigoth commander in charge of Roman soldiers would be a disgrace. Incensed at this antibarbarian sentiment, Alaric ordered Attalus to meet him at Ariminum, on the northeastern Italian coast. There, he took Attalus’s purple robe and diadem away by force and imprisoned him in his own camp.

16

Alaric then marched back to Rome. In August of 410, he arrived at the city’s gates and forced his way in without difficulty. He was angry; he had been trying for years to get recognition from the traditional leaders of Rome, some sort of admission that his skill and his power compensated for his barbarian ancestry, but the recognition always receded away from him. In his bitterness, he told his soldiers that they could plunder the city, taking by force what they had not been given by right. The Visigoths broke into treasuries, stole coins and riches, and set fire to whatever took their fancy (although Alaric told them to spare the churches). Alaric himself took Placida, Honorius’s sister, as his personal captive. The 410 incident became known as the Sack of Rome, even though it didn’t destroy all that much of the city, and even though Rome had suffered much worse attacks. But for the far-flung citizens of the empire, both east and west, it served as a jolting revelation. The Eternal City, the Rome they had assumed would stand forever, was so diminished that a band of Visigoths could overrun it with almost no effort. No band of foreigners had entered the city for almost eight centuries, not since 387

BC

, when the city was not yet part of an empire. Jerome, the young secretary to the bishop of Rome, was now a hermit in his fifties, living in the eastern empire near Bethlehem and still working on his translation of the Scriptures into Latin for the use of the west. “My voice sticks in my throat,” he wrote later, recalling the dreadful news, “and sobs choke my utterance. The City which had taken the whole world was itself taken.”

17

In North Africa, Augustine too mourned. And in response to Rome’s fall, he began to write his great work of history, the

City of God

. It was clear that Rome was no longer—if it had ever been—the Eternal City. It was merely an earthly kingdom that had served the purposes of God in its time, and its time was now past. But what of the bishop of Rome? Did the city’s fall mean that the Christian church too would fade?

It took Augustine thirteen years to work out the answers. Once again he drew on the idea of double existence and dual authority. Rome, he wrote, was a city of man; and in all times, at all places, the cities of men exist side by side with the city of God, the true Eternal City, the unseen spiritual kingdom. Men choose which city they will occupy, and although the goals of the two cities may occasionally intersect (and their citizens may find themselves able to cooperate with each other), the ultimate purposes of their citizens diverge. The city of man seeks power; the citizens of God’s city seek only the worship and glory of God. Rome had fallen, but the city of God would endure forever.

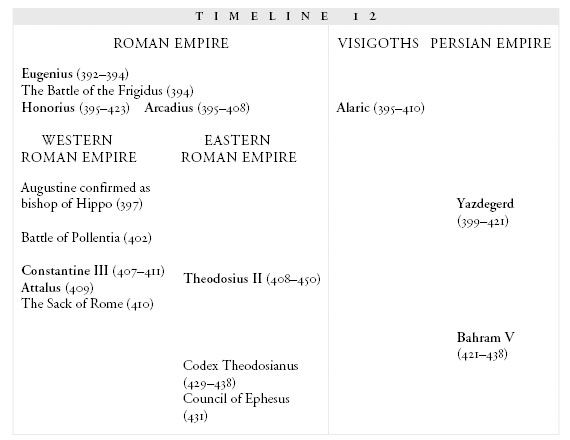

TIMELINE

11

ROMAN EMPIRE | VISIGOTHS | PERSIAN EMPIRE |

Theodosius | | |

Magnus Maximus | | Shapur III |

Theodosian Decrees | | |

Eugenius | | |

The Battle of the Frigidus (394) | | |

Honorius | Alaric | |

WESTERN EASTERN ROMAN EMPIRE ROMAN EMPIRE | | |

Augustine confirmed as bishop of Hippo (397) | | |

| | Yazdegerd |

Battle of Pollentia (402) | | |

Constantine III | | |

Attalus | | |

The Sack of Rome (410) | | |

Between 408 and 431, the Persian emperor makes himself unpopular by protecting the eastern Roman throne, and a quarrel over theology reveals deeper divisions

T

HE EASTERN

R

OMAN EMPEROR

Arcadius had expected to die a violent death, but in the end illness brought him down. He died of natural causes in 408, leaving the crown of the eastern empire to his seven-year-old son, Theodosius II.

Thanks to the guardianship of the Persian king Yazdegerd I, Theodosius II ruled in peace. Yazdegerd took the job of preserving the little boy’s power seriously. He provided an accomplished Persian tutor for the child; he sent the eastern Senate a letter detailing his intentions to keep Theodosius II safe; and he threatened war on anyone who attacked the eastern empire. “Yazdegerd reigned twenty-one years,” the eastern Roman historian Agathias tells us, “during which time he never waged war against the Romans or harmed them in any other way, but his attitude was consistently peaceful and conciliatory.”

1

This attitude did him little good with his own people. The Persian noblemen at his court resented his peaceful policies. By extension, they also loathed his tolerance for Christianity within his domain; to them, Christianity was less a religion than a symbol of loyalty to the Romans. Yazdegerd earned praise from the Christian historians of the Roman empire, but the Persians gave him the nickname “Yazdegerd the Sinner,” and he gets a universally black portrayal from Arab historians. The Muslim writer al-Tabari says, “His subjects could only preserve themselves from his harshness and the affliction of his tyranny…by holding fast to the good customs of the rulers before his period of power and to their noble characters.”

In other words, the Persians looked back with longing at the good old days when they had fought the Romans for dominance. They resisted Yazdegerd’s policies and his decrees until he was driven to more and more drastic enforcement of his own orders. This only justified their bad opinion of him: “His bad nature and violent temper made him consider minor lapses as great sins and petty slips as enormities,” al-Tabari writes, censoriously.

2

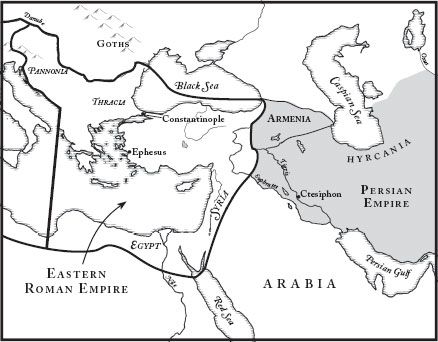

12.1: Persia and the Eastern Roman Empire

Finally, Yazdegerd buckled. When an overzealous Christian priest in Ctesiphon tried to burn down the great Zoroastrian temple there, Yazdegerd sanctioned a full-fledged persecution of the Persian Christians.

This drove a wedge between Yazdegerd and the eastern Roman court—particularly Theodosius II’s sister Pulcheria, two years older than the emperor and a devout Christian. At fifteen Pulcheria, already formidable, had talked the Roman Senate into naming her empress and co-ruler. In 420, when Pulcheria was twenty-one and Theodosius II was nineteen, she convinced him to declare war on his former guardian.

3

Nor did the persecution do enough to mollify the Persian aristocracy. In 421, Yazdegerd died while travelling through Hyrcania, southeast of the Caspian Sea. The official story was that he had been struck by sudden illness, but an old Persian story suggests a more violent end: Yazdegerd was travelling when a spirit-horse rose from a nearby stream, killed him, and then disappeared back into the water. The horse was the symbol of Persian nobility;

something

undoubtedly was lying in wait for the king.

4

The crown prince of Persia, raised by Yazdegerd to carry on his policies, was murdered by courtiers almost at once. The king’s second son, Bahram, came from Arabia, where he had been exiled by his father, to be crowned Bahram V in his brother’s place. Al-Tabari writes that when Bahram came into sight of the palace, Yazdegerd’s former chancellor came out to greet him and was so awe-stricken at his handsomeness that he forgot to perform the ritual prostration with which Persians greeted their rulers: the story reflects the Persian belief in the Avesta, the divine “aura” of the appointed king, the “royal glory” that proved he had the right to hold power. Bahram’s rule was legitimized, just as Theodosius’s had been, by the will of the divine.

5

Avoiding his father’s mistakes, Bahram V carried on the persecution of Christians. He also mounted an aggressive defense against Theodosius II’s declaration of war, assembling an army of forty thousand to march against the frontiers of the eastern Roman empire. It was a short war. Within a year, both Theodosius II and Bahram had decided it would be more prudent to swear a truce instead. Neither empire was dominant, and a war would be long and painful. Both sides agreed to refrain from building new frontier fortresses, and also to leave the Arab tribes on the edges of the desert alone (each empire had been actively wooing the loyalty of the Arab tribes, Persia with offers of friendship, the Romans with Christian missionaries).

“When they had concluded this,” Procopius sums up, “each side attended to its own affairs.”

6

For Theodosius II, this meant getting married to a wife chosen by his sister Pulcheria; all three, brother, sister, and wife, lived together in the royal palace.

Thanks to the Persian-enforced peace of his early years, Theodosius’s court had now achieved the sort of stability that made the eastern Roman realm capable of functioning like an actual empire, rather than like a military encampment whose generals were busy killing each other (the current state of the western empire). Theodosius now had the luxury of actually ruling, instead of just fighting for survival. In 429, he appointed a commission to synthesize all the irregular and competing laws in his part of the empire into a single coherent law code, the Codex Theodosianus.

*

He took credit for the new walls that now protected Constantinople, the Theodosian Walls. And he founded a school in Constantinople for the study of law, Latin, Greek, medicine, philosophy, and other advanced subjects—a school that would eventually gain the name “University of Constantinople,” making it one of the oldest universities in Europe.

This university was designed to take the place of the Roman university of Athens, the last remaining bastion of the old state religion. The intellectual center of the empire had begun to shift to the east, a movement bolstered by the relative peace of the east and the chaos in the west. Furthermore, in the University of Constantinople, there were a total of thirteen “chairs,” or faculty positions, for teachers of Latin, and fifteen for teachers of Greek—a small but significant gain in Greek language and philosophy over the Latin which, thanks to Jerome’s translation of the Bible, continued to be used in the western part of the empire.

7

In 431, Theodosius also had to deal with another theological controversy, one that came to full blaze at the Council of Ephesus.

Arianism (the doctrine that Christ was created by the Father, rather than coexisting with him from eternity) was still alive, but it had been shoved away from the core of the empire, towards its edges: it was the religion of barbarians, a sign of incomplete assimilation to the Roman identity. But the matter of Christ’s exact nature was far from settled. Among those who were orthodox in their adherence to the Nicene Creed, a new division arose: given that Christ was God and also man, just how did these two natures

relate

to each other? There were two schools of thought. The first held that the two natures had become mystically one, united in the person of Christ in a way impossible to tease out by reason; the second, more rational school held that two separate natures, divine and human, were both present but separate, like two different colors of marbles in a jar.

8

The assertion of a single nature became known as monophysitism, while the argument that Christ had two natures mixed together became known as Nestorianism, after Nestorius, bishop of Constantinople and its most ardent supporter.

*

Theodosius II himself was a Nestorian, but when the Council of Ephesus met to hash out the issue, it finally rejected Nestorianism and condemned Nestorius as a heretic. Theodosius II was forced to bow to pressure and exile Nestorius to an Egyptian monastery.

This was a defeat for him, and he felt it. The argument was not just theological hairsplitting. For one thing, there were always political dimensions to the theological debates. This particular controversy was partly about the power centers of the empire: the two-natures-mixed school of theology was centered in the city of Antioch while the more mystical one-nature school was centered in Alexandria. The influence and importance of these two cities were at stake. So was the relative power of ambitious men: Cyril, the bishop of Alexandria, was a one-nature man (as was the bishop of Rome), while the bishop of Constantinople, Nestorius, was a two-nature man. Nestorius’s condemnation made clear that the bishop of Rome still sat at the top of the ecclesiastical heap.

Fear of Persian influence sharpened the argument further. Zoroastrianism, the religion of the Persians, was a monotheistic religion like Christianity; nevertheless it was the religion of the enemy, and the Christians of Rome and Alexandria were suspicious of any Christian doctrines that sounded a little too Zoroastrian. Since Zoroastrianism denied that there could ever be any mixing of divine and earthly substances, Nestorius’s two-nature theology fit into the Persian schema in a way that the mystical one-nature theology never could. This tainted it further, in the eyes of the bishops farther from the border; they suspected that Nestorius had been influenced by Persian philosophies.

9

But the theological debates over the nature of Christ’s divinity cannot be reduced to politics or nationalism. They were the flashpoint of a bigger war, the symbol that two entirely different ways of thinking were about to come into full conflict.

The arguments over Christology were, in fact, not unlike the modern American debates about creationism. A whole complex of ideas is at stake in the defense of a literal creation: a worldview that has some room in it for the supernatural and inexplicable; the fear that conceding this point will lead to the destruction of a moral code; resentment over the superiority and condescension of what are seen as overeducated intellectuals. On the other side, the sharp rejection of

all

creationist assertions (one thinks of the rhetorical excesses of a Richard Dawkins or Sam Harris) also reveals fears: that accepting a mystical explanation of the earth’s beginning will lead to the triumph of irrationality and violence; that concession will boost the earthly power of a particular political group.

And so it was in the fifth century as well. The men who quarrelled over Christology in Alexandria and Rome and Constantinople were also fighting over the place of mysticism and the power of rationalism, the fear of Persian influence and the rejection of all Persian culture—as well as the suspicion that one half of the empire might manage to gain political and practical power over another.