The Beasts that Hide from Man (28 page)

Read The Beasts that Hide from Man Online

Authors: Karl P.N. Shuker

In his book

The Dragons of Eden

(1977), eminent Cornell University scientist Prof. Carl Sagan contemplated a still closer link between fictional dragons and factual giant reptiles, speculating that perhaps some prehistoric reptiles survived into more recent times than currently accepted by science, and that mankind’s myths and legends of dragons may therefore stem from ancient, inherited memories of our long-distant ancestors’ encounters with

living dinosaurs

.

Whereas many continental European dragons were of the classical winged, quadrupedal, fire-disgorging type, most British dragons are of the worm variety, with lengthy, elongate bodies, but limbless, wingless, and emitting poisonous vapors rather than fire. One of the most famous of these vermiform horrors was described as follows:

Ane hydeous monster in the forme of a Wörme…in length three Scots yards and somewhat bigger than an ordinary man’s leg, with a head more proportionable to its length than to its greatness, in forme and colour like to our common muir adders.

This is a medieval description of the Linton worm, a monstrous creature that issued forth from a tributary of Scotland’s River Tweed in the 12th century, to begin a reign of terror within the surrounding countryside. Making a den for itself on Linton Hill, in Roxburghshire, it preyed upon the farmers’ livestock, asphyxiating them with its poisonous breath and sunbathing upon the hill after a heavy meal. In desperation, the local populace offered a huge reward to anyone who would free them from this loathsome beast, and in 1174 their plea was answered by a valiant nobleman, the Laird of Lariston, believed to be a member of the Somerville family.

In the Apocrypha, there is a story of how Daniel killed a dragon by forcing lumps of pitch, fat, and hair into its mouth. The Laird of Lariston adopted a similar means of dispatching the Linton worm, by thrusting down the creature’s throat a lump of burning peat dipped in red-hot sulphur and pitch, attached to the tip of his lance. This dynamic scene is portrayed in a handsomely sculptured tympanum in Linton’s parish church.

Many of Britain’s dragon tales are believed to be wholly fictitious, but there may be at least a core of fact at the base of the Linton worm’s legend. The description of its appearance recalls a very large snake, as does its sunbathing behavior following a meal, and its poisonous breath (like other carnivorous animals, large snakes have foul-smelling breath). It could well have been a python or some other exotic big snake that had escaped from one of the many menageries popular in medieval times. Such cases are far from unknown.

The Wormingford “corkindrill” killed in 1405 on the border of Essex and Suffolk, for instance, was certainly an escapee crocodile from the Tower of London, where it had been maintained since its arrival in England from the Crusades.

In Europe, limbed but wingless dragons were known as lindorms, and several preserved or stuffed specimens of supposed lindorms have been documented over the years. The journal

Notes & Queries

(December 28,1850, and January 18,1851), for instance, mentions a Moravian example suspended in an arched passage leading to Brünn’s town hall; another one hanging from the roof of Abbeville Cathedral, Picardy; and also an example in the church of St. Maria delle Grazie, near Mantua, northern Italy. Such exhibits are generally large lizards or—in the case of the Moravian specimen—crocodiles. However, the “lindorm skull” discovered at Klagenfurt, southern Austria, after being found here in 1335, and which was the inspiration for this town’s impressive sculptured fountain of a lindorm, completed in the late 16th century, was unmasked by zoologist R. Pusching in 1935 as that of a woolly rhinoceros!

It is well known that the many specimens of hideously ugly “taxiderm mermaids” in existence have been skillfully manufactured by sailors and others seeking to part gullible travelers from their money by sewing together the upper parts of monkeys and the lower parts of fish.

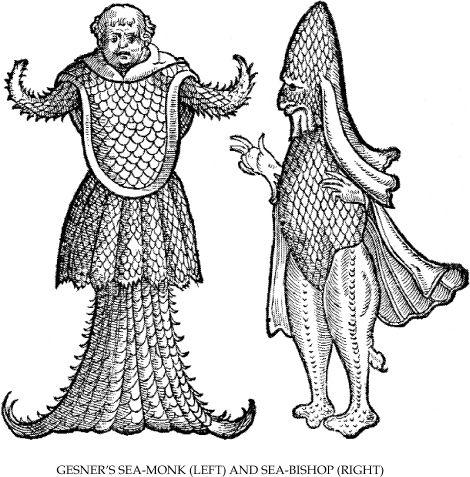

Even more plentiful, however, and equally bizarre in appearance is a multifarious assemblage of preserved marine monstrosities variously dubbed sea-monks, devil-fishes, and Jenny Hanivers. In medieval times, their reality was widely accepted, and hence they were frequently portrayed in bestiaries, alongside sea life of a much more reputable nature.

Thus, on page 174 of Conrad Gesner ‘s

Nomenclator Aquatilium Animantium

(1560), we find two extraordinary engravings. One is of a sea-monk, supposedly caught off the coast of Norway during Gesner’s own lifetime, but which bears a recognizable if somewhat distorted likeness to a large squid (giant squids have often been washed ashore around Scandinavia).

The other is of a so-called sea-bishop, which was allegedly spied in 1531 off the coast of Poland. This too could conceivably be a rather imaginative illustration of a squid, and was possibly the engaging if erroneous outcome of an artist attempting to illustrate a creature known to him only from second-hand descriptions.

Moreover, judging from various suspiciously octopus-like renditions on ancient Greek vases and other depictions from that age and locality, one of Heracles’s most formidable opponents, the multiheaded hydra, was either a monstrous octopus or a colossal squid.

And in a fascinating article published by the American magazine

Natural History

in June 1941, cryptozoological writer Willy Ley put forward an interesting argument in favor of accepting Homer’s description of another, equally terrifying monster of Greek mythology—Scylla, a hideous sea-dwelling entity with six heads on six long necks, and twelve misshapen feet—as the earliest documentation of a giant squid.

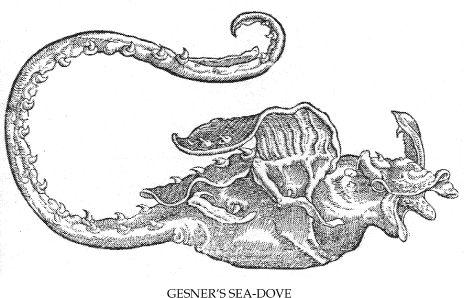

Even more grotesque than Scylla, however, is an engraving on page 166 of Gesner’s aforementioned bestiary, portraying an Indian sea monster that was somehow found in Milan. And on page 33 of the supplement (named

Paralip omena)

of Gesner’s

Historia Animalium Liber IV. Qui est de Piscium et Aquatilium Animantium Natura

, 2nd edition (1604), there can be found an engraving of a truly hideous monstrosity perversely labeled a sea-dove. Looking at both of these freakish fish, however, it is not difficult to discern that they are nothing more than artfully modified, dried specimens of rays or skates. So too are devil-fishes, which can still be bought in curio shops in many a seaside resort in Europe, and also in America, where, keeping up with the times, they are often sold to unsuspecting tourists as the earthly remains of dead extraterrestrials. But that, as they say, is another story!

Most elaborate of all are Jenny Hanivers. Works of art in their own right, these are rarely seen nowadays, but once again originated as dead rays or skates, whose broad lateral fins had been carefully cut, molded, and dried into the shape of curving limbs, thus creating all manner of realistic if decidedly fishy (in every sense!) forms of water dragon.

Perhaps the most surprising relics of a mythical beast, however, are those of the thunder horse. According to Oglala Sioux tradition in Nebraska, Wyoming, and South Dakota, this is a huge, terrifying creature that leaps down from the skies to the earth during storms, and whose sonorous hoofbeats are the origin of thunder. Predictably, scientists initially discounted this as fantasy, until 1875, when the Sioux showed American paleontologist Prof. Othniel C. Marsh some enormous bones that they claimed were from a thunder horse, and which were unlike those of any animal species known at that time! Greatly intrigued, Marsh studied them, and revealed that they were the fossilized remains of a hitherto unrecorded rhino-like relative of horses that had lived about 35 million years ago. Commemorating its links with legend, Marsh dubbed it

Brontotherium

—”thunder beast”—the most famous member today of a totally extinct family of ungulates known as titanotheres.

Everyone is familiar with the age-old legend of the phoenix, in which this exquisitely plumaged Middle Eastern bird, the only one of its kind, dances in the midst of its burning nest until it is entirely consumed by the flames, yet is afterwards miraculously resurrected. But did the phoenix really exist, and how did its extraordinary legend originate?

For centuries, scientists have sought to identify the phoenix with a real bird, such as the peacock, golden pheasant, golden eagle, purple heron, various parrots, and even one or more of New Guinea’s crow-related birds of paradise. This last-mentioned possibility has attracted especial interest, as there are several different birds of paradise that correspond very closely to ancient descriptions of the phoenix’s reputed appearance.

Morphological similarity, however, is not sufficient in itself. After all, how could a bird of Middle East mythology have been based upon any species native to a land as far away from Asia Minor as New Guinea? This remained a seemingly insoluble problem, until 1957, when a team of Australian zoologists, investigating the bird of paradise skin trade in New Guinea, made some extraordinary discoveries.

They learned that although Western science only became aware of these spectacularly beautiful birds’ existence in the 16th century AD, some New Guinea tribes had been exporting their exquisitely plumed skins for untold centuries before this—as far back, in fact, as 1000 BC, when this island was visited by Middle Eastern seafarers from Phoenicia, home of the phoenix legend! The team also learned that to ensure that the fragile skins remained intact during the long, arduous sea voyage back home from New Guinea to Phoenicia, the tribespeople used to wrap them in myrrh, molded into an egg-shaped parcel, and then sealed this inside a second parcel composed of burned banana leaves.

This vividly recalls the phoenix myth, in which the reborn phoenix preserves its nest’s ashes in a package of myrrh, wrapped in turn within aromatic leaves fashioned into the shape of an egg, which it then leaves as a tribute on the altar of the sun god’s temple at Heliopolis. The most startling correspondence between myth and reality, however, is still to come.

To obtain the highest prices for these skins, the tribespeople would naturally have ensured that they were from the most sumptuously plumaged species, and it just so happens that one of these is also one of the most abundant—thereby guaranteeing its plentiful representation in any consignment of skins for export. This species is Count Raggi’s bird of paradise

Paradisea raggiarla

, the male of which is adorned with two lavishly profuse sprays of bright scarlet feathers cascading flamboyantly from beneath its wings. During its pre-mating display, it performs a sensational courtship dance, quivering animatedly and repeatedly elevating its fiery plumes; to a human observer, the visual effect is uncannily like a bird dancing amid a blazing inferno of flame! Descriptions of this extraordinary spectacle retold back home in Phoenicia by maritime voyagers returning from New Guinea, and substantiated by the egg-molded parcels of skins from the exotic species performing this dramatic ritual, would have been more than adequate to inspire the phoenix legend.

Moreover, the celebrated Russian firebird may also have been based upon birds of paradise. In 1961, Soviet scientist V. Kiparsky discussed this thought-provoking concept when contemplating the possibility that their skins had first reached Eastern Europe far earlier in history than previously assumed.

According to the traditional mythology of the Annamite people in central Vietnam, the four corners of Space are ruled by four celestial tigers. The Black Tiger is the ruler of the North, and his empire incorporates winter and water. The Red Tiger rules the South, and governs summer and fire. The White Tiger, ruler of the West, controls autumn and metals. And the Blue Tiger, reigning in the East, is the monarch of spring and plants.

Remarkably, all four of these highly unusual tigers may well have a basis in reality. It is well known that several species of wild cat sometimes produce freak, all-black (melanistic) specimens, due to various mutant genes. The black panther, for instance, is merely a melanistic mutant of the leopard, and melanistic jaguars are also very common. Moreover, although no specimen has so far been made available for formal scientific examination, there are many reports by reliable, experienced eyewitnesses on file of all-black tigers, and in the 1970s, a partially melanistic specimen was born at Oklahoma City Zoo. Genetically, there is no good reason why melanistic tigers should not arise occasionally, and it is quite conceivable that such distinctive specimens inspired the Annamese belief in the celestial Black Tiger.