The Beasts that Hide from Man (26 page)

Read The Beasts that Hide from Man Online

Authors: Karl P.N. Shuker

Nevertheless, Richard believes that the

naga

may have some basis in reality. First evolving in the Cretaceous Period, the madtsoids were a group of primitive but huge snakes that were primarily aquatic, killed by constriction, and, in certain areas of the world, such as Australia, survived until only ten or so millennia ago. The most famous mythical entity of Australian aboriginal Dream-Time belief is the giant rainbow serpent. Although traditionally deemed to be fictitious, it may have been based upon a real creature after all.

In 2000, Queensland University zoologist Dr. Michael Lee, Dr. John Scanlon from New South Wales University, and colleagues proposed that the rainbow serpent might have been inspired by preserved memories of bygone encounters between early aboriginal settlers Down Under and a now-extinct genus of Aussie reptile comprising two species of extremely sizeable python-like madtsoid, the wonambi. Measuring 10 to 16 feet long, with a cross-section the size of a large dinner plate, it would have been big enough to swallow very large creatures, and thus could have readily given rise to legends of immense, all-consuming rainbow serpents. So perhaps the wonambi did survive long enough to have coexisted for a time with the first humans to reach Australia. And what of the Thai

naga—

could this be a living, modern-day Asian madtsoid?

Lastly, but no less intriguingly, Myanmar (formerly Burma) may have its very own version of the

naga

. Zoologist Dr. Alan Rabinowitz’s recent book

Beyond the Last Village

(2001), featuring his explorations of this country, contains some tantalizing details of a hitherto-unpublicized mystery reptile:

In Putao [a northern Burmese village], there were stories about a giant water snake, the bu-rin, 40 to 50 feet long, that attacked swimmers or even small boats. Sounding somewhat like a larger, aquatic version of the Myanmar python, this snake was considered incredibly hostile and dangerous. No one had firsthand knowledge of the creature, yet because of it, children were often discouraged from spending long periods of time in the water.

Is the

bu-rin

merely a fictitious, serpentine bugbear utilized by parents to frighten their children away from dangerous stretches of water, or could it simply be an extra-large, or exaggerated, normal python? Or is it something very different—an undisclosed living fossil? Perhaps yet another slithery surprise is lurking in a far-off region of the world, resolutely unknown to science but only too well known to the local people sharing its remote terrain.

The galagos, or bush-babies, would materialize magicalh), like fairies, ana sit among the branches, peering about them with their great saucer-shaped eyes, and their little incredibly human-looking hands held up in horror, like a flock of pixies who had just discovered that the world was a sinful place

.G

ERALD

D

URRELL

—

E

NCOUNTERS

W

ITH

A

NIMALS

THE VU QUANG OX

PSEUDORYX NGHETINHENSIS

, the giant muntjac

Megamuntiacus vuquangensis

, the Taingu civet

Viverra tainguensis

, and the Panay cloud rat

Crateromys heaneyi

are just a few of the remarkable number of major new mammals described from Asia during the 1990s. Yet none has a more controversial pedigree than the very mysterious mini-mammal supposedly rediscovered during the mid-1990s in southeastern China.

The tangled tale of the Chinese ink monkey (also called the pen monkey) hit the media headlines on April 22,1996, when the

Peoples Daily

newspaper published an account based upon information supplied to it by the official New China News Agency (Xinhua). According to these sources, this amazing little animal was no larger than a mouse, weighed only seven ounces, and had recently been discovered alive in the Wuyi Mountains of Fujian Province after having been dismissed as extinct by Chinese scientists for several centuries. Strangely, however, no additional details concerning its resurrection—precisely when, by whom, the number of specimens recorded, whether any had been photographed or collected, etc.—were given. Nor was its zoological species identified, or any extensive morphological description supplied.

In contrast, details of its “pre-extinction” history were as profuse as they were perplexing. Supposedly known in China since at least 2000 BC, the ink monkey was so named because it was the traditional pet of scholars and scribes—and for good reason. Despite its tiny size, the ink monkey was very highly intelligent—so much so that a writer would frequently train one to prepare his ink for him, turn the pages of a manuscript that he was working on or reading, and pass brushes to him as required. Ever the practical, diligent pet, a writer’s ink monkey would even sleep in his master’s desk drawer or brush pot. Zhu Xi (AD 1130-1200), a famous Neo-Confucian philosopher, allegedly owned one of these obliging little helpers, yet sometime later the species seemed to have become extinct (an unexpected occurrence for so useful a beast, I would have thought) until its belated reappearance during the mid-1990s.

Those, then, were the “facts” of a very odd cryptozoological case—but they served only to enhance rather than to elucidate the mysteries encompassing this extraordinary animal.

First and foremost of these was its identity—what exactly

was

—or

is

—the ink monkey? The world’s smallest known living primate is itself a recent revival, the western rufous mouse lemur

Microcebus myoxinus

of Madagascar, measuring a mere 7.75 inches long, and weighing just over one ounce. This tiny species was first described by science back in 1852, but was subsequently believed to have died out until its rediscovery in 1993. Could it be that the ink monkey report was a confused retelling of this lemur’s reappearance? In view of the historical background details presented above, this seemed highly unlikely.

Turning from lemurs to monkeys, however, shed little light on the problem either. The world’s smallest formally recognized species of monkey is the pygmy marmoset

Cebuella pygmaea

of the Upper Amazon Basin, with a total length of around 10 inches. Yet mainstream zoology knows of no species of Chinese monkey as small as a mouse, nor, as far as I am aware, are there any reports of such a beast in the cryptozoological literature either. Nevertheless, the ink monkey is not entirely unknown to Westerners.

I am greatly indebted to Steve Moore, a renowned specialist in Oriental Fortean-related literature, for bringing the following excerpt to my attention, which appeared in a book of Chinese lore by E.D. Edwards,

The Dragon Book

(1938), page 149:

THE INK-MONKEY

This creature is common in the northern regions and is about four or five inches long; it is endowed with an unusual instinct; its eyes are like cornelian stones, and its hair is jet black, sleek and flexible, as soft as a pillow. It is very fond of eating thick Chinese ink, and whenever people write, it sits with folded hands and crossed legs, waiting till the writing is finished, when it drinks up the remainder of the ink; which done, it squats down as before, and does not frisk about unnecessarily.

Edwards obtained these engrossing snippets from a Chinese author called Wang Ta-Hai, writing in 1791, whose work was translated into English as a two-volume tome titled

The Chinese Miscellany

(1845,1849).

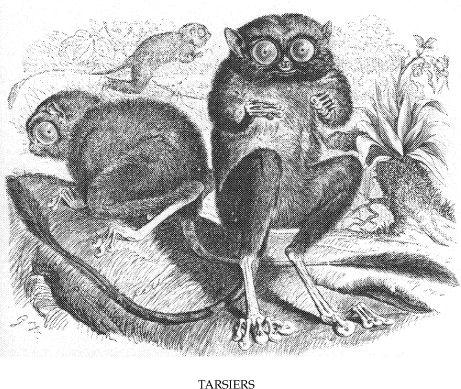

Whereas Edwards’s description may initially conjure forth bizarre images of a red-eyed pixie with an insatiable ink lust, it also calls to mind certain real-life creatures, such as the bushbabies or galagos, and, especially, those real-life goblins of the golden eyes, the tarsiers. These tiny arboreal primates weigh only a few ounces and have brown or grey bodies measuring no more than six inches. Tarsiers are distantly related to bushbabies and lemurs, and are characterized by their large ears, enormous orb-like eyes, very long tarsal bones, flattened sucker-like discs at the tips of their fingers and toes, and a long thin tail.

Traditionally comprising a trio of species indigenous to Borneo, Sumatra, the Philippines, and Sulawesi, in recent times at least three more species have been recognised from Sulawesi and its offshore islets—the pygmy tarsier

Tarsius pumilus

in 1987, Diana’s tarsier T.

dianae

in 1988, and the Sangir tarsier T.

sangirensis

in January 1996. Could the ink monkey be yet another lately revealed tarsier? During a radio interview broadcast on April 24,1996, concerning the ink monkey in which he expressed the view that it may possibly be a tarsier, veteran British wildlife broadcaster Sir David Attenborough noted that tarsiers did exist in southern China a long time ago, and that such secretive, nocturnal creatures as these might conceivably have succeeded in surviving in small numbers amid this region’s thick forests right up to the present day while remaining undetected by science.

Conversely, during the same interview, Cyril Rosen of the International Primate Protection League favored the slow loris

Nycticebus coucang

as a plausible contender, whose southeast Asian distribution range may indeed extend into southeastern China.

Yet even if one or other of these identities were correct, how could such an animal be trained to prepare ink? Back in the centuries when the ink monkey allegedly assisted writers in this manner, ink was normally compounded from a precise array of precious materials, such as sandalwood, musk, gold, pearls, and rare herbs or bark, yielding a stick of ink. Consequently, it was suggested in Western media accounts that perhaps the ink monkey was trained to grind the stick in an inkstone with pure water until the correct shade was obtained. Nevertheless, such valuable constituents as those listed above are hardly the types of material that most people would entrust to a monkey (or tarsier) for handling.

Moreover, aside from Edwards’s curious contribution that the ink monkey not only prepares but also consumes ink, there were no details as to its dietary preferences. Tarsiers, unlike most other primates, are entirely carnivorous. So if the ink monkey is indeed a tarsier, what might we expect its favorite food to be? When a colleague’s enquiries at the news agency in Xinhua that released the original press information concerning the ink monkey revealed that the agency had no record of where they had actually received their own details(!), I began to suspect that fillet of red herring—or perhaps even a tasty canard?—may well prove to be the answer.

In other words, it seemed likely that the whole episode of the Chinese ink monkey was either a bizarre hoax from start to finish, or, more probably, simply the benighted product of confused reporting. Quite possibly, for instance, a Chinese media report had somehow been erroneously translated by Western journalists so that its true subject, one of China’s lesser-known non-existent beasts of fable and folklore, had falsely “become” a real-life animal that had been rediscovered after several centuries of supposed extinction.

And in case this hypothesis seems too implausible, I recommend readers to peruse an entire chapter devoted to several comparable cases of monstrous misidentification exposed in all their glorious folly, within one of my earlier books,

From Flying Toads to Snakes With Wings

(1997).

Nevertheless, it would be reassuring if the original source of such confusion could be traced. For a time, I was unable to do this, but eventually, when resurveying zoological reports from April 1996, I came upon a short piece that had not attracted anywhere near as much attention as the Chinese ink monkey story, and which I had not seen before, yet which assuredly presented me with the missing piece of this extraordinary cryptozoological jigsaw.

The report was a short but succinct item published by London’s

Times

newspaper on April 5,1996 (three weeks before the ink monkey reports). It recorded the discovery in China’s Yellow River basin of fossil jaw remains from a mouse-sized primate dubbed

Eosimias centennicus

, which had lived 40 to 43 million years ago, and weighed a mere three to four ounces. Needless to say, this description tantalizingly echoes the sparse details available in the subsequent reports dealing with the Chinese ink monkey.

Consequently, the most reasonable explanation for this entire episode is as follows. Somewhere in the early portion of the chain of journalistic communication ultimately giving rise to the ink monkey media stories in the West, details of the discovery of the

Eosimias

fossils, documented correctly in

The Times

, became distorted elsewhere, and were mistakenly combined with the traditional Chinese ink monkey folklore—until the tragi-comical result was the rediscovery of a creature that had never existed.