The Beasts that Hide from Man (32 page)

Read The Beasts that Hide from Man Online

Authors: Karl P.N. Shuker

Nevertheless, the creature depicted in Topsell’s book bears no resemblance to a baboon—even allowing for the fact that medieval illustrations of animals were often notoriously inaccurate. Nor does it look like the Barbary ape

Macaca sylvanus

, a tailless species of macaque monkey native to North Africa (including Libya long ago) but renowned for the largely human-introduced colony on Gibraltar. In fact, Topsell’s picture does not recall any type of monkey.

At present, therefore, verification of the mimiek dog as a baboon remains unproven, but perhaps this is fitting. After all, it would be nothing if not ironic if science quite literally made a monkey out of a creature best known for aping around.

In Madagascar fortunate circumstances have almost enabled us to watch the extinction of the giant fauna of the past, but we have missed our opportunity

.BERNARD HEUVELMANS—

ON THE TRACK OF UNKNOWN ANIMALS

BUT HAVE WE REALLY MISSED OUR OPPORTUNITY? Since the early 1980s, several species of lemur have been newly discovered, or rediscovered after being presumed extinct, on their island homeland, Madagascar. Moreover, there could be some dramatic cryptozoological encounters of the lost lemur kind still to be made here.

TRATRATRATRA

Take, for instance, the

tratratratra

. This mysterious beast was first brought to Western attention by Admiral Etienne de Flacourt in his

Histoire de la Grande Isle Madagascar

(1658). He described it as a very solitary animal: “as big as a two-year-old calf, with a round head and a man’s face; the forefeet are like an ape’s, and so are the hindfeet. It has frizzy hair, a short tail and ears like a man’s.” He also noted that a

tratratratra

had been seen near the Lipomani lagoon, and revealed that the native people and this sizeable creature shared a great fear of one another, each fleeing when catching sight of the other.

No present-day Madagascan mammal fits the

tratratratra s

description, but it does sound very reminiscent of a supposedly long-extinct giant lemur known as

Palaeopropithecus

, which was as big as a chimpanzee and probably spent at least some of its time on the ground because of its large size. In particular, its flattened face would have looked ape-like or even humanoid, thus differing noticeably from the arboreal, dog-faced lemurs predominating in Madagascar today, but readily recalling the

tratratratra. Palaeopropithecus

supposedly became extinct one thousand years ago, due to hunting and habitat destruction, but some zoologists believe that it may have persisted a few centuries longer, explaining reports of the

tratratratra

.

Indeed, it is not impossible that this extraordinary “lost” lemur has actually lingered into the 20th century. As recently as the 1930s, a French forester in Madagascar claimed to have observed at close range an amazing, unidentified lemur unlike any that he had ever seen before. According to his description, it resembled a gorilla, sat four feet high, lacked a muzzle, and possessed “the face of one of my ancestors”! Was it a surviving

Palaeopropithecus?

—TITAN OF THE TREES

Equally controversial is the

tokandia

, which is said to be a huge quadrupedal jumping beast that climbs up into trees and cries like a man, but does not have a man-like face. French cryptozoologist Dr. Bernard Heuvelmans has likened this remarkable mystery beast to a real-life Madagascan monster of sorts,

Megaladapis

, the largest lemur of all time.

Probably weighing over 200 pounds,

Megaladapis

was the size of a small bear, and its skull was rather like that of a rhinoceros but with heavy cow-like jaws. It may have sported a prehensile tapirlike snout too, for pulling tasty foliage towards its mouth. Yet despite its great size, it is believed to have been arboreal, clinging to the trees like a colossal koala.

So could

Megaladapis

and the

tokandia

be one and the same? Like

Palaeopropithecus, Megaladapis

“officially” died out at least a millennium ago, but surely it is more than a coincidence how closely this “lost” lemur compares with the tantalizing

tokandia?

—YET ANOTHER LIVING FOSSIL?

No less fascinating is the

kidoky

. December 1998 saw the publication in the journal

American Anthropologist

of a remarkable scientific paper, by Fordham University biologist Dr. David A. Burney and Madagascan archaeologist Ramilisonina, in which they documented ethnographic data collected by them during late July-early August 1995 at the remote southwestern Madagascan coastal fishing village of Belo-sur-mer. Their paper contained accounts by several local eyewitnesses describing what they claimed were quite recent sightings of two scientifically unidentified creatures. These are known respectively as the

kilopilopitsofy

(“floppy ears”—also termed the

tsomgomby

—which may be a relict representative of one of Madagascar’s two officially extinct species of pygmy hippopotamus) and the

kidoky

. Witnesses were questioned independently of each other, and prompting for specific answers was avoided wherever possible. A measure of how zoologically accurate and trustworthy the knowledge and testimony of each witness were likely to be was ascertained by asking each witness to identify local faunal species from unlabeled color plates. The results obtained generally satisfied the authors that the eyewitnesses were indeed knowledgeable and trustworthy concerning their region’s fauna.

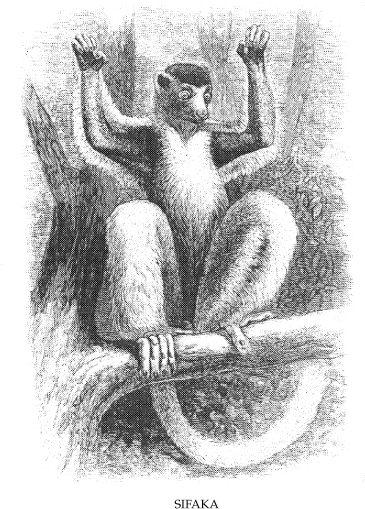

Of the seven major interviewees whose details were tabulated in the paper, the most authoritative and informative was an old villager called Jean Noelson Pascou, who had keen eyesight and was literate. When questioned about the

kidoky

, Pascou, and also some recent woodcutter eyewitnesses, compared it in basic form with those moderately large, primarily arboreal lemurs known as sifakas, but the

kidoky

was said to be much bigger. Based upon a close sighting of one in 1952, Pascou claimed that it has dark fur but a white spot on its brow and another below its mouth. Apparently, the

kidoky

is usually encountered on the ground, and flees by running (via a series of short, forward, baboon-like leaps, instead of via the characteristic sideways leaping gait always adopted by sifakas when on the ground), rather than by taking to the trees. Its long whooping call is like that of the large dog-headed indri, but it has a rounder man-like face, more like a sifaka’s than an indri’s.

As conceded by Burney and Ramilisonina, this description brings to mind two officially extinct genera of giant lemur,

Archaeolemur

and

Hadropithecus

. Both possessed many terrestrial modifications, and have been likened to baboons anatomically and behaviorally Conversely, radiocarbon datings place both as having been extinct for well over 300 years at least, probably longer —but have they?

AND

MANGARSAHOC

—LEMURS IN SHEEP’S CLOTHING?

Also in need of an explanation are the

habéby

or

fotsiaondré

reported from the Isalo range by the Betsileo tribe, and the

mangarsahoc

of Anosy The

habéby

is said to be a nocturnal sheep with long furry ears, a white coat dappled with black or brown, a long muzzle, and large staring eyes. Yet no one has ever reported seeing a horned

habéby

, i.e. a

habéby

ram. In view of this odd omission, and also bearing in mind that whereas sheep are not normally nocturnal and do not have large staring eyes, while many lemurs are and do, zoologists consider it much more likely that the

habéby

was (or is?) an unknown species of large lemur.

This identity can also be applied to the

mangarsahoc

, traditionally described as a very large nocturnal ass or horse but with such enormous ears that they hang down over its face. As with the

habéby

, it is said to bring bad luck to anyone who sees it—and similar superstitions are attached to many of the lemur species known today.

Even the bizarre-looking aye-aye

Daubentonia madagascariensis

, resembling a goblinesque squirrel, may have a cryptozoological counterpart. There was once a larger version, the giant aye-aye D.

robusta

—whose skeletal remains indicate that it was a third bigger than the typical aye-aye. Although the giant aye-aye supposedly died out many centuries ago, there is an intriguing piece of evidence to suggest that this noteworthy species may have still been alive much more recently. A scientific paper from 1934 noted that near the village of Andranomavo in the Soalala District, a government official called Hourcq saw a native hunter holding the skin of an exceptionally large aye-aye—so large, in fact, that some researchers feel that it might indeed have been from a modern-day specimen of the giant aye-aye.

“Lemur” is a Malagasy word meaning “ghost,” but judging from the reports reviewed here, some of Madagascar’s “lost” lemurs may be far more substantial than any ghost!

SEA SERPENT:

No one has counted his geniais and gastroliges yet, nor computed his parietals and described his superaoculars, though there s plenty would like to and pickle him to boot and stick him in a museum for people to peer at

.C

HARLES

G. F

INNEY

—

T

HE

C

IRCUS OF

D

R

. L

AO

OFTEN UTTERED WITH NO LESS VEHEMENCE THAN Salome’s demand for the head of John the Baptist, the title of this chapter reflects the response traditionally elicited from most zoologists when confronted with the suggestion that the vast oceans may contain notably large species of sea creature still unknown to science—and that some such species could explain that most controversial maritime enigma, “the great sea serpent.”

Needless to say, fleeting glimpses of a head and neck (or sometimes merely an ill-defined series of humps) all-too-briefly surfacing before sinking back beneath the waves can hardly substitute for adequate

physical

evidence—a head, or a body!—that can be subjected to formal scientific analysis in order to determine categorically the taxonomie identity of its owner. One might assume, therefore, that if such evidence does come to hand, the end of the mystery must surely then be in sight. But as readily demonstrated by the following selection of cases, the course of true cryptozoology seldom runs quite as smoothly as that!

Possibly the most famous of these cases occurred at Stronsay, one of the Orkney Islands off northern Scotland. On September 26,1808, John Peace was fishing east of Rothiesholm Point when he saw what seemed to be the carcass of a whale, cast up onto the rocks, above which were flocks of circling seabirds. He rowed up to it in his boat and examined it, and found that it was a very peculiar-looking creature which did not resemble anything known to him. At that same time, farmer George Sherar was watching Peace from the shore, and was able to confirm all of this. About 10 days later, moreover, he was able to see it for himself, because it was washed ashore on Stronsay, lying on its belly just below the high tide mark.

When Sherar discovered it there, he measured it, and found it to be 55 feet long. Others also measured it, and obtained the same result. It was very serpentine, almost eel-like in general build, but possessed a 15-foot neck, a small head, and a long mane running along its back to the end of its tail. Most bizarre of all, however, was that it seemed to have three pairs of legs, and each foot had five or six toes. Sherar salvaged some vertebrae and the skull of this extraordinary creature, which became known as the Stronsay beast.

Details of its discovery and description ultimately reached Patrick Neill, secretary of Edinburgh’s Wernerian Natural History Society, and at a meeting of the society on November 19,1808, Neill released some details on this subject. At the next meeting, on January 14, 1809, he gave the Stronsay beast a formal scientific name:

Halsydrus pontoppidani

, “Pontoppidan’s water snake of the sea/’ after Erik Pontoppidan, an 18th century Norwegian bishop who had collected many sea serpent reports.