The Beasts that Hide from Man (23 page)

Read The Beasts that Hide from Man Online

Authors: Karl P.N. Shuker

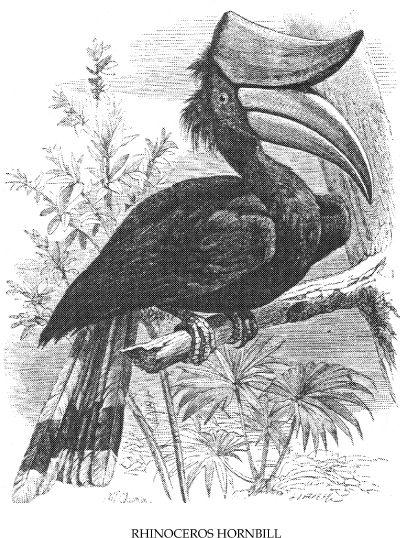

Although I think it exceedingly unlikely that the

kusa kap

, at least in the form of the above description, will ever prove to be anything more than an inhabitant of the imagination, it is worth noting that the rhinoceros hornbill

is

known to produce a sound with its wings that has been likened by listeners to the noise of a chugging steam train. Perhaps, then, the

kusa kap

is an undescribed relative of this species, still awaiting official discovery on one of the Torres Strait’s islets, and whose dimensions have been greatly exaggerated in local traditions. It would not be the first time that an impossibly flamboyant animal of native legend has been shown to conceal at its core a much more sober but indisputably real species in need of formal scientific recognition.

The same may be true of the superficially improbable bird spied by a Mr. Sporing in the 18th century on New Zealand’s Jubolai Island. According to a record of this sighting in the journal of Joseph Banks (Captain Cook’s Botany Bay naturalist) for October 1769:

While Mr. Sporing was drawing on the island he saw a most strange bird fly over his head. He described it as being about as large as a kite, and brown like one; his tail, however, was of so enormous a length that he at first took it for a flock of small birds flying after him: he who is a grave thinking man, and is not at all given to telling wonderful stories, says he judged it to be yards in length.

Were it not for the fact that there are no such species native to New Zealand, it would be tempting to identify this form as one of those excessively long-tailed birds of paradise known as astrapias, indigenous to New Guinea. The most spectacular of these, the ribbon-tailed bird of paradise

Astrapia meyeri

, was not even discovered until 1938; the male has only a tiny body, but sports an extraordinary tail composed of two enormous white feathers—each of which is at least a yard long.

New Zealand was once home to two very impressive eagles reminiscent of the formidable South American harpy eagle

Harpia harpy ja

, but with longer limbs. Known respectively as

Harpagornis moorei

and

H. assimilis

, and believed from the evidence of various incomplete remains to have been stronger and more heavily built than any of today’s eagles, with a wingspan of around seven feet, these mighty raptors were once thought to have died out as long ago as the 12th century. However, Maori legends tell of two gigantic, terrifying birds referred to as the

hokioi

and the

poua-kai

(this latter was supposedly a man-eater, according to South Island’s Waitaha tribe), whose descriptions tally closely with reconstructions of the

Harpagornis

species from fossils. In fact, many ornithologists now consider it possible that one or both of these eagles persisted until as recently as the 17th century—and that if it had not been for the extermination by humans of their likely prey, the smaller species of moa, they might have survived even longer.

There is no doubt that they must have been a breathtaking sight in life, but a quite recent discovery showed that they were even more spectacular than hitherto suspected. At the beginning of 1990, it was announced that the first

complete

skeleton of a

Harpagornis

eagle had been found, concealed deep inside a cave of Mount Owen, near Nelson, South Island

(Daily Telegraph

, January 17,1990). From this extremely important find, an adult

H. moorei

, scientists were able to deduce that in life its species would have weighed about 35 pounds, and had a wingspan of up to 10 feet. Little wonder, then, that

Harpagornis

has been preserved in the Maoris’ memories—the sight of a predatory bird soaring overhead on wings spanning 10 feet across is not one to be readily forgotten!

In another part of the world, moreover, such a sight can still be made today—at least according to the natives of the Peoples Republic of the Congo, who firmly believe in the existence of an enormous type of monkey-devouring eagle called the

ngoima

. During his searches in the 1980s for this country’s most famous mystery beast, the swamp-dwelling dinosaur-like

mokele-mbembe

, cryptozoologist Dr. Roy P. Mackal also received details of the great

ngoima

bird, from one of its most eminent eyewitnesses—André Mouelle, the country’s political commissar. Mouelle stated that it had a huge wingspan of nine to 13 feet, preyed upon monkeys and goats, dwelt within the dense forests, and was armed with talons as large as a man’s hands, legs as big as a man’s forearms, and a downward-curving hooked beak. Its plumage was blackish-brown above, with somewhat paler underparts.

As Mackal discusses in his book

A Living Dinosaur?

(1987), the

ngoima

corresponds quite closely both in appearance and in prey preference to the martial eagle

Polemaetus bellicosus

(if we assume that the upper limit of the

ngoima s

wingspan as given by Mouelle is an overestimate); but whereas the

ngoima

is reputedly a forest dweller, the martial eagle is a bird of open country. In contrast, there is another, albeit slightly smaller species that shares not only the

ngoima’s

morphology and prey preference but also its forest-dwelling habitat. This is the crowned eagle

Stephanoaetus coronatus

, the most powerful (yet also the least-observed) eagle in Africa. Indeed, it corresponds so closely with the

ngoima

on every count other than the latter bird’s immense wingspan that Mackal considers the search for the

ngoima s

identity to be at an end, with the dramatic dimensions of its wings merely the product of human exaggeration (when confronted unexpectedly by the daunting presence of this rarely spied species), rather than any legitimate manifestation of nature.

Nevertheless, as revealed in this chapter, there are plenty of other ornithological oddities still in need of satisfactory explanations—enough, in fact, for even the most adventurous birdwatcher to get into a flutter about!

Forth from the dark recesses of the cave The serpent came; the Hoamen at the sight Shouted; and they who held the priest, appall’d, Relaxed their hold. On came the mighty snake, And twined in many a wreath around Neolin, Darting aright, aleft, his sinuous neck, With searching eye and lifted jaw, and tongue Quivering; and hiss as of a heavy shower Upon the summer woods. The Britons stood Astounded at the powerful reptiles bulk, And that strange sight. His girth was as of man, But easily could he have overtopp d Goliath’s helmed head; or that huge king Of Basan, hugest of the Anakim. What then was human strength if once involvd Within those dreadful coils! The multitude Fell prone and worshipped

.R

OBERT

S

OUTHEY

—

M

ADOC

. T

HE

C

URSE OF

K

EHAMA

ALL THAT GLITTERS IS NOT GOLD. AND ALL THAT slithers is not snake—or is it? Peruse the following pentet of limbless—or near-limbless—cryptids, and judge for yourself!

Sometimes, the briefest words attract the greatest interest. So it was when, in the closing section of my book

In Search of Prehistoric Survivors

(1995), I included the following line: “I have on file reports of a mysterious jumping snake reported from the environs of Sarajevo.” Since then, I have received numerous communications from readers requesting further details—more, in fact, than for almost any other mystery beast noted by me anywhere. So here, at last, is what I know about the Sarajevo jumping snake.

In reality, this mystifying serpent has been reported widely across the old, pre-fragmented Yugoslavia, but I first learned about it from a chapter on alleged jumping snakes in Dr. Maurice Burton’s book

More Animal Legends

(1959). Burton quoted a lengthy letter from Mr. M.R Kerchelich of Sarajevo, which included the following important excerpts:

We have in Yugoslavia a dreaded specimen [species] of jumping snakes called locally ‘poskok’, meaning ‘the jumper’…found mainly in Dalmatia along the east coast of the Adriatic and the mountainous regions of Hercegovina [sic] and Montenegro. In fact, there exists an island near Dubrovnik called ‘Vipera’, which is a well-known breeding place of ‘the jumper’. The average size of this snake is between 60 and 100 cm, though considerably larger specimens were seen. The colour seems to vary, according to environment, from granite grey to dark reddish brown. The snake is dreaded for its poison and aggressiveness when disturbed, though it will usually hide on approach of man…1 can vividly remember three cases of meeting the ‘poskok’, the first was in Montenegro, when on a trip I stopped the car to stretch my legs. It was lying in the middle of the road, some 100 metres ahead of the car, sleeping in the sun. After watching it for some time it must have felt my presence, curled up and jumped into a dry thorn bush at the kerb of the road and disappeared. The jump was at least 150 cm long and some 80-90 cm high. On the second occasion I was driving a jeep in southern Dalmatia and, coming round the corner, I could just see a snake about to cross the road. The car must have frightened it and quite suddenly it jumped at the front mudguard and was killed by the rear wheel. The third time I met a ‘poskok’ was when I was fishing a small stream in Croatia and leaning against a dry tree trunk. Suddenly I noticed a hissing sound above me, and, having been warned of snakes, scrutinised my surroundings more carefully. It took me quite a time to discover that one of the dry branches was not a branch at all but a ‘poskok’ watching me intently…All three specimens I have seen were not more than about 3 to 4 cm in diameter at the thickest point.

Burton gave reports of jumping snakes from elsewhere, too, including his own sighting of a grass snake leaping across a ditch that was one foot deep and two feet wide, and his experience of another grass snake apparently leaping with lightning speed over the wall of a vivarium, by stiffening its body in a vertically erect position. Burton concluded: “the ability [of snakes] to progress in vertical jumps becomes at least feasible. All that is needed is the stimulus.”

Thus, Burton did not consider the

poskok’s

disputed jumping ability to be zoologically impossible. However, he offered no opinion whatsoever regarding its taxonomie identity.

I later mentioned the

poskok

to London University zoologist Professor John L. Cloudsley-Thompson, an expert in reptilian behavior. In a paper titled “Reptiles That Jump and Fly/’ published by the

British Herpetological Society Bulletin

in 1996, he commented: “cryptozoologists have reported a mysterious jumping snake from the environs of Sarajevo. Could this be

Coluber viridiflavus

, the western whip snake?”

Unfortunately, this species’ distribution only extends into the northwestern section of the former Yugoslavia. However, three of its close relatives—the Balkan whip snake C.

gemonensis

(which greatly resembles it), the large whip snake C.

jugularis

, and Dahl’s whip snake C.

najadum

—all occur much more widely in Yugoslavia. Exhibiting quite a range of colors, including those reported for the

poskok

, these species are of similar size to it too, and the large whip snake can also attain the larger sizes sometimes claimed for it. Moreover, all are very slender, fast-moving, aggressive when captured, and given to biting hard. In stark contrast to the

poskok

, conversely, they are not venomous.

Coupling its venom with the name of the Dubrovnik island— Vipera—where the

poskok

is said to breed, I favored one of Europe’s several species of viper as a more likely candidate (always assuming, of course, that it does not comprise a hitherto undescribed species). Three vipers are known to occur widely in the former Yugoslavia—Orsini’s viper

Vipera ursinii

, the common viper (adder)

V. berus

, and the nose-horned viper

V. ammodytes

. Moreover, one of these—the nose-horned viper—is highly venomous.

In August 1998, I was contacted by Marko Puljic, of Yugoslavian descent, who had read my brief snippet in

Prehistoric Survivors

, and had afterwards communicated with Croatian herpetologist Dr. Biljana Janev. In her reply to Marko, Dr. Janev stated that the

poskok

was indeed the nose-horned viper, continuing: “Its name [poskok—‘jumper’] comes from the belief that it can jump [far], which is not accurate. Rather, it is able to jump like many other snakes (maybe 0.5 metre, and that is the ‘lunging’ during an attack). Maybe the reason is that the snake, particularly in autumn, climbs on shrubs and low trees where it can hunt young birds. Believably [Presumably], if it attacks, it looks like it has jumped quite a way”