The Beasts that Hide from Man (12 page)

Read The Beasts that Hide from Man Online

Authors: Karl P.N. Shuker

Several authorities have boldly attempted to equate the

olitiau

with a pterodactyl, in preference to a giant bat. Interestingly, in parts of Zimbabwe and Zambia a creature supposedly exists whose description vividly recalls those long-extinct flying reptilians. It is known to the natives as the

kongamato

, and has been likened by them to a small crocodile with featherless, bat-like wings—a novel but apt description of a pterodactyl!

In the case of the

olitiau

, however, Sanderson remained adamant that it was most definitely a bat of some kind, albeit one of immense dimensions—which is why he was so interested by Bartels’s account of the

ahool

, which indicated that undiscovered giant bats were by no means limited to Africa. In fact, it is now known that similar animals have also been reported from such disparate areas of the world as Vietnam, Samoa, and Madagascar. Madagascar’s version is known as

thefangalabolo

(“hair-snatcher”), named after its alleged tendency to dive upon unsuspecting humans and tear their hair (a belief reminiscent of the Western superstition that bats can become entangled in a person’s hair).

If giant bats do exist, how much bigger are they than known species, and to which type(s) of bat could they be related? The answer to the first of these questions is simple, if startling. The largest living species of bat whose existence is formally recognized by science is the Bismark flying fox

Pteropus neohibernicus

, a fruit bat native to New Guinea and the Bismark Archipelago; it has a total wingspan of five and a half feet to six feet. Assuming that eyewitness estimates for the wingspan of the

ahool

and the

olitiau

are accurate, then both of these latter creatures (if one day discovered) would double this record. The question of their taxonomie identity is a rather more involved issue.

Known scientifically as chiropterans (“hand-wings” because the greater portion of their wings are membranes of skin extending over their enormously elongated fingers), the bats are traditionally split into two fundamental but quite dissimilar suborders.

The megachiropterans, or mega-bats for short, comprise the fruit bats. Often called flying foxes as many have distinctively vulpine (or even lemur-like) faces, these are a mostly large, primarily fruit-eating species, and rely predominantly upon well-developed eyes for avoiding obstacles during night flying.

The microchiropterans, or micro-bats for short, comprise all of the other modern-day bats. Often small and insectivorous, but also including some vegetarian and fish-eating forms, as well as the notorious blood-sipping vampires of tropical America (certain micro-bats are very large too, almost as big as the biggest fruit bats), these emit ultrasonic squeaks for echo-location purposes when flying at night.

Descriptions of the

ahool

and

olitiau

are similar enough to suggest that they belong to the same suborder—but which one?

In view of their size, it would be reasonable to assume, at least initially, that they must surely be mega-bats, and with the

olitiau

in particular there are certain correlations that seem on first sight to substantiate this.

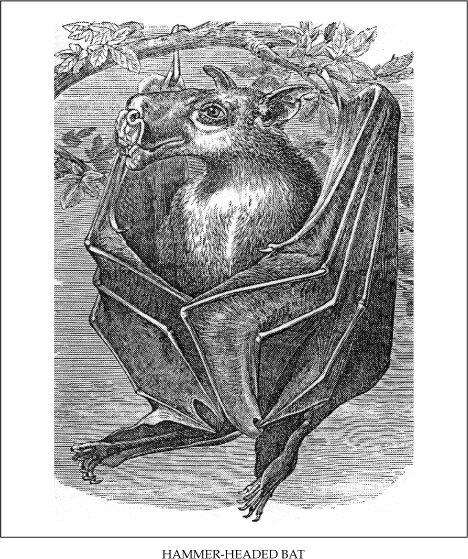

Paul du Chaillu is best remembered as the (in)famous author of grossly exaggerated, lurid descriptions of the gorilla, as encountered by him during his mid-19th century expeditions to tropical Africa. Less well known is that he was also the discoverer of this vast continent’s largest species of bat—a hideous yet harmless fruit bat with a three-foot wingspan known scientifically as

Hypsignathus monstrosus

. On account of its grotesquely swollen, horse-shaped head and an oddly formed muzzle that ends abruptly like the blunt end of a hammer, it is referred to in popular parlance as the hammer-headed or horse-headed bat, and is native to central and western Africa, where it can be commonly found along the larger rivers.

This is particularly true during the dry seasons, when the males align themselves in trees bordering the riverbanks and saturate the night air with an ear-splitting Babel of honking mating calls and loud swishing sounds generated by the frenetic flapping of their 18-inchlong wings. A human traveler unsuspectingly intruding upon such a scene as this might well be forgiven for fearing that he had descended into one of the inner circles of Dante’s Inferno!

In truth, this hellish gathering is nothing more fiendish than the communal courtship display of the male hammerheads—each male hoping to attract the attention of one of the smaller, less repulsive females, which select their mates by flying up and down these rows of rowdy suitors, evaluating the potential of each male performer.

On account of its fearsome appearance, large size, and preference for riverside habitats,

H. monstrosus

has been proposed on more than one occasion as a contender for the identity of the

olitiau

. Yet even under the dramatic circumstances surrounding their Cameroon visitation, it is highly unlikely that Sanderson and Russell could have mistaken a bat with a three-foot wingspan for one with a 12-foot spread, especially as they were both very experienced wildlife observers. Moreover, it just so happens that only a few minutes before their winged assailant made its sinister debut, Sanderson had actually shot a specimen of

H. monstrosus

, so the singularly distinctive physical form of this species was uppermost in his mind. Hence, if the mystery beast that appeared just a few minutes later had genuinely been nothing more than a hammer-headed bat, Sanderson would surely have recognized it as such.

Another problem when attempting to reconcile the

olitiau

with this identity is the

olitiau s

belligerent attitude—for in stark contrast, the hammer-headed bat has a widespread reputation as a harmless fruit-eater with a commensurately tranquil temperament. Having said that, however, I must point out that this ostensibly mild-mannered monster does have a lesser-known, darker side to its nature too, one that is much more in keeping with its gargoylesque visage.

As divulged by American zoologist Dr. Hobart Van Deusen

(Journal of Zoology

, 1968), in startling violation of the fruit bat clan’s pledge of frugivory

H. monstrosus

has been exposed on occasion as a clandestine carnivore—because it has been seen to attack domestic chickens, alighting upon their backs and viciously biting them, and it will also carry off dead birds.

Could the

olitiau

therefore be an oversized, extra-savage relative of the hammer-headed bat? In short, an undiscovered giant member of the mega-bat suborder?

Thought provoking though this identity may be, when documenting the subject of giant bats in his book

Investigating the Unexplained

(1972) Ivan Sanderson disclosed that there is also some arresting evidence in support of the converse explanation— namely, that these gigantic forms are in reality enormous micro-bats. This radical notion, which is particularly convincing when applied to the

ahool

, is substantiated by several independent, significant features drawn from these creatures’ morphology and lifestyle.

For example, whereas the flattened man-like or monkey-like face of the

ahool

and

olitiau

contrasts markedly with the long-snouted face of most mega-bats, it corresponds well with that of many micro-bats. The presence of both forms of giant mystery bat near to rivers, and the

ahool’s

reputedly piscivorous diet, also endorse a micro-bat identity as many species of micro-bat are active fish-eaters, but there is none among the mega-bats. When the

ahool

has been spied upon the ground, or perched upon a tree branch, its wings have been closed up at its sides; a micro-bat trait again— mega-bats fold their wings around their bodies.

Perhaps the most curious, but also the most telling (taxonomically speaking), of the statements by the Sundanese natives concerning the

ahool

is that when observed upon the ground it had stood erect, with its feet turned backwards. To someone not acquainted with bats, all of this may seem nonsensical in the extreme—after all, whoever heard of bats that can stand upright, and which come equipped with back-to-front feet? Yet, paradoxically, these are the very features that vindicate most emphatically the opinion of Sanderson that this mystery creature not only is a bat (rather than a bird or some other winged animal) but is specifically a giant form of micro-bat.

To begin with: although not widely known, micro-bats are indeed capable of standing virtually erect (even though they

mostly

run around on all fours when on the ground); mega-bats, however, never attempt this feat. And switching from feats to feet: those backward-pointing appendages of the

ahool

are worthy of special note too.

There are a few species of bird that habitually hang downwards from branches in a manner reminiscent of bats. These include Asia’s

Loriculus

hanging parrots (also called bat parrots for this reason); and, during their courtship displays, the males of New Guinea’s blue bird of paradise

Paradisaea rudolphi

and the Emperor of Germany’s bird of paradise

P. guilelmi

. If these birds are observed from the front when hanging upside-down, their feet can be seen to wrap around the front portion of the branch, i.e. their toes (excluding the hind ones) curl

away

from the observer, toward the back of the branch.

With bats, however, the reverse is true—their feet wrap around the rear portion of the branch, with their toes curling

towards

the observer. This is because bats’ feet really do point backwards— and so, in the event of a bat standing on the ground, its feet would indeed be projecting backwards, precisely as the

ahool’s

Sundanese observers have described.

Combining the

ahool’s

rearward-oriented feet with its ability to stand upright when on the ground, its identification as an immense micro-bat is thereby lent credence by noteworthy anatomical correspondences—correspondences, moreover, that its native eyewitnesses are unlikely to have appreciated (in terms of their taxonomie implications), and which they would therefore not have incorporated purposefully into their

ahool

accounts if they had merely invented the beast as a hoax with which to fool gullible Westerners.

The possible existence of any type of giant bat with an 11-to12-foot wingspan, let alone one that is most probably a micro-bat rather than a mega-bat, is bound to raise many an eyebrow and inspire many a derisory sniff within the zoological community The prospect, furthermore, that there are other such species, in Africa, Madagascar, and elsewhere, too, all successfully evading official discovery and description, may well stimulate even more profound manifestations of incredulity and disdain.

Perhaps, then, these skeptics should pay a visit to western Java and listen for the eerie cry that the wind and good fortune wafted in the direction of Bartels’s startled ears; or to western Africa and stand by a silent river to see whether Sanderson’s night-winged visitor will swoop out of the evening shadows and into the zoological history books. All of this has happened before — why should it not happen again?

Whereas the previous mystery bats were distinguished by their huge size, the next one is of notably diminutive dimensions—indeed, this is the very characteristic that enables it to indulge in the bizarre day-roosting activity that has incited such scientific curiosity.

It all began in 1955, when John G. Williams, a renowned expert on African avifauna, was taking part in the MacChesney Expedition to Kenya, from Cornell University’s Laboratory of Ornithology. In June of that year he encountered Terence Adamson, brother of the late George Adamson of

Born Free

fame, and during a conversation concerning the wildlife inhabiting the little-explored forests of Mount Kulal, in northern Kenya, Adamson casually mentioned a peculiar little bat that had attracted his interest—by virtue of its unique predilection for spending its days snugly concealed inside dry piles of elephant dung, of all things.

Bats are well known for selecting unusual hideaways during the daylight hours, requisitioning everything from birds’ nests to aardvark burrows, but there was no species known to science that habitually secreted itself within the crevices present in deposits of elephant excrement. As a consequence, Adamson had been eager to discover all that he could regarding this extraordinary creature.

He had first encountered one of its kind during a walk through Kenya’s Marsabit Forest (of which he was warden). After idly kicking a pile of elephant dung lying on the path he was strolling along, he saw a small grey creature fly out of it and alight upon a tree nearby. Expecting it to be nothing more notable than some form of large moth, Adamson was very startled to find that it was an exceedingly small bat, with silver brownish-grey fur, paler upon its underparts. He was especially surprised by its tiny size— its wingspan was even less than that of the familiar pipistrelles, which are among the smallest of bats. Unfortunately, he was only able to observe it for a few moments before it took to the air again and disappeared, but his interest was sufficiently stirred for him to make a determined effort thereafter to seek out other specimens of this odd little animal.