Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany (15 page)

Read Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany Online

Authors: Julian Stockwin

In 1580 Drake became the first English sea captain to circumnavigate the globe. By the time he returned to Plymouth in September of that year he had rounded Cape Horn through the strait named after him, sailed up the coast of Peru, ballasted his ship with Spanish gold and silver, landed on the shore of California, crossed the Pacific, reached the East Indies and the Spice Islands and sailed back via the Cape of Good Hope.

So vast was the treasure that he brought back with him that it was reckoned to meet the cost of an entire year’s government. It was destined for the royal coffers, but Queen Elizabeth privately told Drake to take £10,000 for himself and the same for his crew.

Drake devoted much time to civic affairs and politics, but whenever he could he returned to sea. He boasted of ‘singeing the King of Spain’s beard’ after an audacious raid on Cadiz in 1587 and a year later played his part in the defeat of the Spanish Armada, after coolly completing a game of bowls on Plymouth Hoe.

at the Bar

When in London Drake

was

sometimes a visitor to the Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, one of the inns of court. The high table in the hall consists of three 8.8-m planks of a single oak, reputedly a gift from Elizabeth I, cut down in Windsor Forest and floated down the Thames. The members of the inn still dine there as they did one evening in August 1586 when Drake, just back from a successful expedition against the Spaniards, was rapturously congratulated by all around the table. The hatch cover of his galleon

Golden Hinde

was later used to make the present ‘cupboard’, the table on which new barristers sign the roll book after being called to the Bar

.

Drake captures a Spanish treasure-ship

Drake captures a Spanish treasure-ship.

DELIVER A BROADSIDE – give a forceful rebuke that ends all further discussion.

DERIVATION

: a broadside was the simultaneous firing from one side of the ship of every cannon that could be brought to bear on the enemy. In a three-deck ship of the line with 50 guns or more this meant a considerable weight of ironmongery!

ATHER OF METEOROLOGY

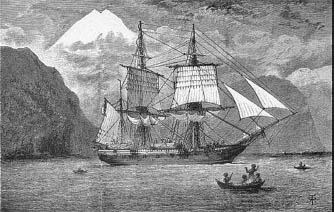

Robert Fitzroy captained the famous second survey voyage of HMS

Beagle

in which Charles Darwin developed his revolutionary theory. This association with one of the world’s most influential men has somewhat overshadowed the contributions Fitzroy made to weather science.

During the first voyage Captain Pringle Stokes committed suicide at sea and Lieutenant Robert Fitzroy was appointed as

Beagle

’s captain. In February 1829, the new commanding officer found his ship blown on her beam-ends by a sudden violent squall. Only great skill in seamanship saved the day, but two crewmen had been swept from the rigging and drowned.

There had been a sharp drop in barometric pressure just before the squall, and Fitzroy’s traumatic experience prompted him to wonder if a more systematic means could be devised to forecast bad weather. In 1843 he suggested that barometers be distributed along the coast of Britain to provide early warning of storms, but nothing came of this.

In 1854 the Board of Trade created a Meteorological Department and Fitzroy was made its superintendent. In 1857, by now an admiral, Fitzroy designed a simple robust ‘Fishery Barometer’ (which soon became known as the Fitzroy barometer) on which were inscribed weather lore rhymes such as ‘When rise begins after low, squalls expect and clear blow’. With the financial assistance of a number of philanthropists he distributed 100 of the barometers to various seafaring centres and lifeboat stations.

Despite his efforts, in 1859 a well-found ship, the iron-clad steam clipper

Royal Charter

, sank in a storm off the Welsh coast resulting in nearly 400 deaths. The tragedy led to calls for the Meteorological Department to extend its activities by not only collecting weather statistics but also using the new telegraph network to send storm warnings to coastal centres, albeit the storms were probably already in progress. Fitzroy went further and developed his department into a unit for producing ‘weather forecasts’, a term he had coined in 1855.

By 1861 Fitzroy had in place a comprehensive system for getting out weather information and storm warnings which he coordinated from his London office. He then went on to produce a daily weather forecast, something no one had ever seriously attempted to do, which was published in

The Times

. However, the forecasts inevitably attracted attention when they were wrong and Fitzroy was subjected to public ridicule and condemnation in the House of Commons.

Fitzroy worked himself into the ground in his efforts to improve the quality of his forecasts. Going deaf and suffering from exhaustion and

depression

, on 30 April 1865 Admiral Fitzroy committed suicide at his Surrey home. It was a tragic echo of the fate of the captain of HMS

Beagle

from whom he took over.

In 2002, when the shipping forecast sea area ‘Finisterre’ was renamed to avoid confusion with the Spanish sea area of the same name, the new name chosen by the Meteorological Office was ‘Fitzroy’ in honour of their founder.

HMS

HMSBeagle

in the Straits of Magellan

.

W

HERE ARE WE

?

Since the early days of sail mariners had been able to calculate latitude (their north–south position) by measuring with instruments the angular height of a star or the sun above the horizon. But a reliable way of calculating longitude (their east–west position) remained elusive until the late eighteenth century. As vessels undertook longer voyages this became an increasing problem. The loss of some 2,000 seamen in October 1707 when Sir Cloudesley Shovell’s fleet sailed to disaster on the Scilly Isles brought clamours for a solution.

In 1714 the government of Great Britain offered a prize of £20,000 to anyone who could provide a solution to the problem of how to calculate longitude at sea. To administer and judge it a Board of Longitude was set up. The task was to invent a means of finding longitude to an accuracy of 30 nautical miles after a six-week voyage to the West Indies.

John Harrison was a Yorkshire carpenter by trade. He had only a limited education but developed a keen interest in machinery. Legend has it that at the age of six he was confined to bed with smallpox and was given a watch to amuse himself. He spent hours listening to it and carefully studying its moving parts. Harrison set out to tackle the problem of longitude in the most direct way – by attempting to produce a reliable clock that would not be affected by temperature, humidity and the rigours of being at sea. The idea was to be able to compare local time to that of Greenwich time, to which the chronometer would be set, and thus find the ship’s longitudinal position. It would take him 30 years of development and experimentation.

In 1735 Harrison completed the first of his timepieces, T1. It was heavy and cumbersome, but he continued his work, encouraged by an award of £500 from the Board, and fired by the gritty determination of a Yorkshireman. After two more versions, T2 and T3, Harrison completed his fourth timepiece in 1759, and with T4 he hoped to claim the prize. This was demonstrated to fall well within the accuracy range specified by the contest. However, there was disagreement within the Board and delays for further testing.

Harrison began work on T5, which he sent to George III to test, whose interest in science was well known. The king was pleased with its accuracy and appealed to the Prime Minister on Harrison’s behalf. In 1773 Harrison was awarded £8,750, but the Board insisted this was a bounty, not the prize.

In 1772 James Cook had taken one of Harrison’s ‘sea clocks’ with him on his second voyage. When he returned in 1774 he pronounced it completely satisfactory, having been able to make the first accurate charts of the South Sea Islands. Cook took the timepiece with him again on his third and final voyage.

Harrison died in 1776. The Board of Longitude was disbanded in 1828, and although the main prize was never actually awarded, Harrison had been the main winner with disbursements over time in effect totalling the amount of the prize money offered.

Harrison’s first four sea clocks are preserved in working order today in the National Maritime Museum.

John Harrison

John Harrison.

T

HE BUCCANEER WITH AN ENQUIRING MIND

William Dampier was born in Somerset, England, in 1652. He was orphaned while a teenager and started his sea career apprenticed to a ship’s captain on a voyage to the Newfoundland fisheries. He so hated the cold, however, that he made sure the rest of his travels were to the tropics, first as a sailor before the mast on an East Indiaman to Java.

When he returned he served in the Royal Navy for a time. He then worked as a sugar plantation manager in Jamaica, after which he found employment with the logwood cutters in Campeachy, Mexico. The dye of the logwood was highly prized for textiles but it was arduous work. The area was the nursery of English buccaneers at the time and Dampier found himself attracted to their free-wheeling lifestyle.

Much of his life at sea from then on was as a buccaneer. Dampier circumnavigated the globe three times, visiting all five continents and taking in regions of the world largely unknown to Europeans.

When not engaged in plunder he took careful notes of the places he visited – their geography, botany and zoology and the culture of the indigenous peoples. He carried his journal with him in a joint of bamboo sealed with wax at both ends. It was published in 1697 as

A New Voyage Around the World

and was followed by several other popular books. As a result Dampier was taken up by London society and he came to the notice of the British Admiralty. In 1699 he was sent on a voyage of discovery around Australia in HMS

Roebuck

. Unfortunately he lost the ship when it was wrecked at Ascension Island, which ruled out any further employment with the Royal Navy. He went back to buccaneering.

Future navigators benefited from Dampier’s geographic surveys and observations, especially his ‘Chart of the General and Coasting Winds in the Great South Ocean’, 1729. This was the world’s first integrated pattern of the direction and extent of the trade-wind systems and major currents around the earth.