Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany (17 page)

Read Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany Online

Authors: Julian Stockwin

Sometimes, as the political map changed over the years, foreigners who signed on when their countries were neutral later found themselves transformed into the enemy.

In 1808 the captain of HMS

Implacable

recorded in the ship’s books that 14 per cent of the men were non-British. He did not find this exceptional, reflecting that if anything it was a bit lower than in other ships he knew of. In King George’s navy as a whole there were sailors from England, Ireland, Wales, the Isle of Man, Scotland, Shetland, Orkneys, Guernsey, Canada, Jamaica, Trinidad, St Domingo, St Kitts, Martinique, Santa Cruz, Bermuda, Sweden, Denmark, Prussia, Holland, Germany, Corsica, Sicily, Minorca, Ragusa, Brazil, Spain, Madeira, USA, West Indies and Portugal.

Even at the Battle of Trafalgar, where an all-British crew might have been expected, around 10 per cent were non-British. In fact there were 108 Frenchmen in the British fleet, four of whom were in

Victory

. Most of the best French seamen came from Brittany and Normandy, areas that had many Royalist sympathisers.

Spinning a yarn to messmates

Spinning a yarn to messmates.

W

ATCH YOUR HEAD!

It was almost impossible for an officer to stand upright in the wardroom in many men-of-war, and only those seated in areas without beams directly overhead could get to their feet with some semblance of dignity. In those ships with a pronounced ‘tumble-home’, steeply sloping sides, this was even more of a challenge.

One concession to this is that in the Royal Navy the Loyal Toast to the monarch is drunk seated. William IV, the ‘sailor king’, was sent to sea at the age of 13 and saw active service in America and the West Indies. He reputedly bumped his head so many times toasting his father that he vowed that when he became king no officer would suffer a similar fate.

As well as the Loyal Toast, a number of others were popular in the wardroom:

Sunday: | ‘Absent friends’ |

Monday: | ‘Our ships at sea’ |

Tuesday: | ‘Our men’ |

Wednesday: | ‘Ourselves, as no one else is likely to concern themselves with our welfare’ |

Thursday: | ‘A bloody war or a sickly season’ |

Friday: | ‘A willing foe and sea room’ |

Saturday: | ‘Sweethearts and wives – may they never meet’ |

The Thursday toast is a reference to the opportunity for promotion via a dead man’s shoes, in peacetime often the only way to get ahead.

RED CHECKED SHIRT AT THE GANGWAY

’

To our modern sensitivities discipline at sea in the age of sail appears very harsh, but it has to be seen in the context of the times – ashore a person could be sentenced to death at the gallows for a minor misdemeanour.

The Articles of War provided the legal basis for discipline in the Royal Navy, but the severity of punishment varied greatly from ship to ship, depending on the captain. Admiralty regulations allowed a maximum of 12 lashes with the cat-o’-nine-tails, but this was often ignored on the grounds that the man had offended in several ways at once.

A captain was not limited to the formal offences as specified in the Articles of War. He could punish ‘according to the laws and customs and in such cases used at sea’, and the punishments meted out could include flogging, an admonishment, the stopping of grog or the disrating of a petty officer.

On punishment day, at six bells in the forenoon watch, the order was given, ‘All hands to witness punishment.’ The master-at-arms presented the offender to the captain, who questioned the man about his alleged offence and then delivered a verdict. The officer of the offender’s division was asked if he had anything to say in mitigation. If this did not satisfy the captain he ordered the man’s punishment. For a flogging the man was stripped to the waist and tied to a grating. The bosun’s mate then extracted the cat-o’-nine-tails out of a baize bag. Some of the tougher seamen took pride in receiving ‘a red checked shirt at the gangway’ without crying out.

However, the captain’s jurisdiction was limited; he did not have the power of life or death and could not order some of the more extreme punishments. The most serious crimes, such as mutiny, arson and cowardice, were dealt with by court martial, which had to consist of at least five and not more than 13 captains and admirals. If a sailor was sentenced to death by a court martial he was hanged, whereas an officer was shot. The last capital punishment carried out in the Royal Navy was the execution of John Dalliger in 1860 on board HMS

Leven

.

Flogging around the fleet was one of the punishments that could only be ordered by a court martial. It involved being rowed from ship to ship with the victim bound to a triangle of spars and receiving a set number of lashes while alongside each. Incredibly, some survived the ordeal, including William Mitchell (500 lashes), who went on to achieve a King’s commission and eventually the rank of admiral. The terrible punishment of keel hauling, in which a man was dragged under the ship’s keel to the other side, his flesh torn by barnacles in the process, was permitted in the Dutch navy, but never used in the Royal Navy.

A midshipman who committed a misdemeanour was usually mastheaded. This meant being sent to the cross-trees at the top of the mainmast. There he had to sit exposed to all weathers until he was allowed to return to the deck.

A number of punishments could be awarded by the junior officers or petty officers without the formality of trial by a captain. The most common were ‘starting’, which meant hitting the man on the back with a knotted rope’s end; ‘gagging’, tying the mouth open with an iron bolt between the teeth; and ‘spreadeagling’, securing him with limbs outstretched up in the shrouds.

Some punishments were carried out by the men themselves, ‘running the gauntlet’ for theft, or being turned out of a mess for objectional behaviour.

The Royal Navy officially suspended flogging in 1879, and to this day it is still suspended, not abolished…

Mastheaded

Mastheaded.

RUN THE GAUNTLET – attacked or threatened with attack, physically or metaphorically, from all sides.

DERIVATION

: in the age of sail ‘running the gauntlet’ was a punishment for thievery which obliged the accused sailor to make his way between two rows of his shipmates, each of whom was armed with a knotted rope to beat him. The master at arms went in front of the unfortunate man walking backwards with a cutlass drawn to prevent him getting through too quickly.

T

THE BAND OF BROTHERS

Nelson used this phrase on a number of occasions. It is from Shakespeare’s play

Henry V –

‘We few, we happy few, we band of brothers.’ Nelson’s original Band of Brothers were all captains at the Battle of the Nile in 1798 and they were the élite of the navy. Fifteen in number, they had known Nelson for a number of years and there was a unique trust and understanding between them.

Not all of the Nile captains were equally close to Nelson; he had an inner circle that he consulted regularly, and they then conveyed the results of these meetings to the remainder. But this inner circle was not static. Of the original Nile captains only Thomas Hardy served in all of Nelson’s later battles. Alexander Ball became governor of Malta, and Ralph Miller was killed in an accidental explosion at the siege of Acre.

Captain George Westcott was the only one of the celebrated band to die at the Nile. He was born of humble origins and left a widow and daughter. Nelson made a point of visiting them and presented Mrs Westcott with his own Nile medal saying, ‘You will not value it less because Nelson has worn it.’

The phrase ‘band of brothers’ later came to mean any captains who were close to Nelson.

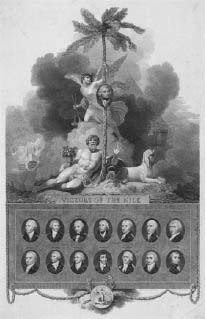

The Nile captains

The Nile captains.

R

IGHT GOOD STOCKHOLM TAR

A true man-of-war’s man was said to be:

Begotten in the galley and born under a gun

Every hair a rope yarn

Every tooth a marline spike

Every finger a fishhook

And his blood right good Stockholm tar

The rich aroma of pine tar has long pervaded sailing ships. Its use as a preservative for wood and rigging dates back at least 600 years. Stockholm tar (sometimes known as Archangel tar) is the most valued and derives its name from the company which for many years had a monopoly on its production in Sweden.

International politics influenced supplies of tar. In the eighteenth century England was cut off from Scandinavian supplies by Russia’s invasion of Sweden–Finland. By 1725 four-fifths of England’s tar and pitch came from the American colonies. This changed again with the American Revolution.

Stockholm tar with its distinctive resinous tang was used by a sailor to dress his queue, his clubbed plait of hair – hence his familiar name of Jack Tar. Not to be confused with this, pitch from the tar lakes of Trinidad, and sometimes called asphaltum, was used for caulking, the process of waterproofing the seams between planks on deck.