Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany (10 page)

Read Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany Online

Authors: Julian Stockwin

His devotion to the navy and belief in its supremacy was summed up by his statement in the House of Lords when the threat of invasion from France was at its height: ‘I do not say, my Lords, that the French will not come. I say only they will not come by sea.’

Earl St Vincent, naval hero of rigorous self-sufficiency and professionalism

Earl St Vincent, naval hero of rigorous self-sufficiency and professionalism.

KNOW THE ROPES – have skill and experience.

DERIVATION

: it took years to understand the function of, and be able to locate and control, the multitude of ropes (or lines, as most of them were known to mariners) in a man-of-war. This ability was considered so important that a skilled seaman’s discharge papers were marked ‘knows the ropes’.

A

ALL DOWN TO BISCUITS AND A BOULDER

HMS

Pique

, a frigate designed by the famed naval architect Sir William Symonds, left Quebec in September 1835. As she sailed out of the mouth of the St Lawrence River a thick fog descended. The ship hit a reef and was battered relentlessly against the rocks all night. In the morning her captain Henry Rous finally freed her by jettisoning 20 cannon and a large quantity of water to lighten the ship.

As soon as she got into deep sea a gale blew up and she began to take in water badly. To add to her troubles

Pique’s

rudder was carried away and the only way she could be steered was by trimming sails and trailing hawsers. A temporary rudder was eventually fitted, but this too was soon swept off. Unable to go about on the right tack for England she eventually managed to signal a passing French brig who obliged by heaving her bodily around.

Pique

was now taking in 1 m of water an hour and the pumps were manned day and night. Deep below in the bowels of the ship the carpenter worked tirelessly to plug what leaks he could.

The gale continued throughout the whole voyage, and when

Pique

finally limped into Portsmouth a dockyard inspector said he had ‘never seen any ship enter port in such a state’. She was found to have virtually no keel left, and in some places the torn floor timbers were wafer thin. A large hole was discovered to have been plugged by a sack of ship’s biscuits swollen with the sea water, and a huge rock 4 m in circumference was snapped off in the hull, stopping up a monstrous cavity midships.

Rous later told Symonds, ‘Your beautiful ship has had the hardest thumping that ever was stood by wood and iron.’

The very rock that was embedded in

Pique

may be seen today in the grounds of the Portsmouth Historic Dockyard.

Promoted to admiral in 1852, Henry Rous was a lover of horse racing from boyhood. He did much to bring fairness to the sport by devising a weight-for-age scale

Promoted to admiral in 1852, Henry Rous was a lover of horse racing from boyhood. He did much to bring fairness to the sport by devising a weight-for-age scale.

‘W

HERE SHALL I FIND A MATCH FOR THIS?’

Irishman Jack Spratt was a good-looking, high-spirited master’s mate aboard HMS

Defiance

at the Battle of Trafalgar. During the action Captain Durham ordered him to lead a boarding party to take

L’Aigle

, but the ship’s boats were found to be shot through. Undeterred, Spratt called the boarders to follow him, snatched a cutlass and leapt overboard to swim to

L’Aigle

, where he soon found himself in fierce hand-to-hand fighting. He was attacked by several soldiers, and having just fought them off and deflected a bayonet thrust at him by another he was severely injured in the leg with a musket ball.

Meanwhile

Defiance

had managed to come alongside and the boarding party leapt to the deck. Through the smoke one of the first people Captain Durham spotted on

Aigle

was Spratt, his bloody leg dangling over the rail. ‘Captain, poor old Jack Spratt is done up at last,’ he called out, and he was hauled back aboard

Defiance

.

Spratt was taken to the surgeon, who wanted to amputate the leg, but he refused. The surgeon appealed to Durham to intervene and order the operation. The captain tried to reason with Spratt, but he merely held up his good leg and said, ‘Never! If I lose my leg, where shall I find a match for this?’

Spratt was landed at Gibraltar, where he was hospitalised for four months. He kept his leg but was lame for the rest of his life. He achieved the rank of commander and retired to Devon, where he was often seen riding on a small Dartmoor pony. Despite his incapacity Spratt retained his swimming skills and when he was nearly 60 years old he swam a 23-km race for a wager and won.

THE FIRST EUROPEAN

sea voyages that impelled the West into an unparalleled age of world discovery and trade were launched by Portugal’s Prince Henry the Navigator in the early fifteenth century. Before that voyages had been coastal, keeping always within sight of land. Other nations quickly followed the Portuguese, notably the Spanish, the Dutch and the English. For the often illiterate sailors crewing the ships, these voyages were frightening journeys into the unknown. Many had fears that they would perish horribly in the infamous Green Sea of Darkness, a terrifying place of lurking monsters and boiling seas.

But more than a century before Christopher Columbus set sail, China mounted seven great exploration voyages under Zheng He, the Admiral of the Western Seas. He sailed to western Asia, Africa and Arabia, visiting some 40 countries. Zheng He’s voyages heralded a momentous period of exploration and trade for China.

In the Golden Age of Sail inventive minds were tackling every kind of problem, from how to plot your position to ship-to-shore rescue. One of the most poignant of their achievements was Henry Winstanley’s lighthouse on the Eddystone reef, the first to be built in the open sea. It was a true feat of human invention and withstood a fiercely unforgiving environment for five years. During the titanic storm of 1703 Winstanley was on it with his men. When the tempest abated he and his lighthouse had completely vanished.

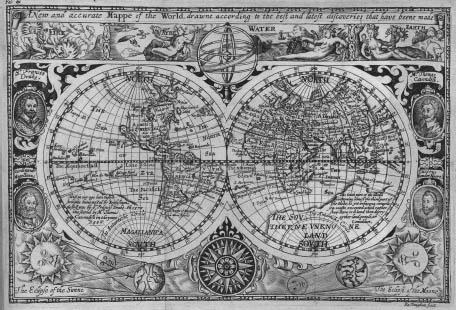

Engraved world map, from a book printed in 1628 compiled by Francis Drake’s nephew

Engraved world map, from a book printed in 1628 compiled by Francis Drake’s nephew.

A

DMIRAL OF THE WESTERN SEAS

Zheng He was a Muslim born in China’s mountainous province of Yunnan in 1372. The Ming Dynasty had been established in 1368, bringing to an end Mongol rule. At the age of 11, Zheng He was captured and castrated when Ming forces were sent to Yunnan to destroy the last stronghold of the old regime. His reputation for bravery had been noted, however, and he was assigned to a royal household where over time he became very powerful. As an adult he was described as brave and quick-witted, a tall, heavy man with clear-cut features, long earlobes and a stride like a tiger.

When his master seized the Peacock Throne and became Emperor Yong Le, he made Zheng He ‘Admiral of the Western Seas’. Over the next three years an incredible flotilla of sailing ships was built under his direction, ushering in a golden period of exploration and trade for China, and making her the most advanced seafaring nation in the world.

Seven great exploration fleets commanded by Zheng He set

sail

between 1405 and 1433; they were the mightiest the world had ever seen. The first carried 28,000 people in around 300 vessels, including the treasure ships which were of extraordinary size. Nine-masted, 120 m long and 49 m wide, each ship could carry more than 1,000 passengers.

Nina

,

Pinta

and

Santa Maria

, the three ships of Columbus built more than a century later, would all fit easily inside a

single

Chinese treasure ship.