Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany (28 page)

Read Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany Online

Authors: Julian Stockwin

When Nelson was wounded and carried below, Hardy remained on the quarterdeck directing the battle. It was well over an hour before he could clamber down to see his friend. Hardy was able to tell Nelson that they had taken 12 or 14 of the enemy vessels, and then he returned to his post.

Another hour passed before Hardy could find time to visit Nelson for a second time. They shook hands and Nelson told Hardy to be sure to anchor. After reminding him to take care of ‘poor Lady Hamilton’ he said, ‘Kiss me, Hardy.’ Hardy responded with a kiss on the cheek and then, after a brief reflective pause, a second on the forehead. Nelson’s last words to his captain were ‘God bless you, Hardy’. Hardy then withdrew and returned to the quarterdeck.

Nelson’s life was by now draining fast and he was drifting in and out of consciousness. With his eyes closed he murmured softly, ‘Thank God I have done my duty.’ These were his last words.

WHEN PORT ROYAL

, Jamaica, ‘the richest and wickedest city in the world’, was swept into the sea in 1692, many saw it as retribution for an immoral existence. But the sea is not an agent of revenge, nor is it cruel; it is indifferent, an elemental, primal force. The seaman turned novelist Joseph Conrad once said, ‘If you want to know the age of the earth, look upon the sea in a storm.’ And the poet Lord Byron described the sea as ‘dark-heaving, boundless, endless, and sublime. The image of Eternity…’

Since the early days of sail countless brave souls who have set forth on the bounding main have not returned. It might be supposed that sea battles have taken the largest toll in human life, but this is not the case. During 20 years of war between 1793 and 1813 approximately 100,000 men in the Royal Navy died – 6.3 per cent from enemy action, 12.2 per cent from shipwreck and other disasters and 81.5 per cent from disease or accident.

Fire at sea was particularly feared by sailors. In ships made almost entirely of combustibles – wood, canvas and tarred cordage just waiting for a flame – a small blaze could very quickly become an inferno. One of the unforgettable images of the Battle of the Nile is the fire aboard

L’Orient

, the massive French flagship. Such was the amazement on both sides at the intensity of the conflagration and the resulting explosion that the entire battle actually stopped for a short time. But of all the causes of death at sea one

looms

above all the rest – scurvy. The dreaded affliction was responsible for more deaths at sea than all the other causes combined, and it probably killed two million sailors during the Golden Age of Sail.

‘

‘The Shipwreck’, a nineteenth-century engraving

.

‘A

N ERROR OF HIS PROFESSION’

It should have been a glorious homecoming after successful operations against the French at Toulon, but it became one of the worst disasters in the history of the Royal Navy. In October 1707 the Mediterranean Fleet under Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell in HMS

Association

set sail from Gibraltar bound for England.

As they neared the English Channel bad weather made them unsure of their position. The admiral consulted his navigators, who believed they were west of Ushant (Ile d’Ouessant) off the Brittany peninsula, well south of any hazards – but in reality they were 160 km north. Shortly afterwards

Association, Romney

and

Eagle

were driven on to rocks off the Scilly Isles and sank with the loss of all on board except the quartermaster of

Romney

. Over 1,300 perished, all down to a combination of bad weather and the inability of mariners in those times to determine their position with accuracy.

Many tales have endured over the centuries about this tragic event, ranging from Shovell hanging a seaman who tried to warn him of impending danger to a local woman murdering the admiral when he was washed ashore in order to steal a large emerald ring that he wore on his hand.

Shovell was initially buried in a simple grave at Porth Hellick, a small community on one of the Scilly isles, but his body was later exhumed and reburied in Westminster Abbey. One newspaper of the day commented, ‘It was very unhappy for an admiral, reputed one of the greatest sea commanders we ever had, to die by an error of his profession.’

Some good did come out of this tragedy – the Admiralty instigated a search for a way of calculating longitude. In 1714 they offered a prize of £20,000 for a solution, but it was many decades before a way was found of determining an accurate position with a chronometer (

see here

).

HE PIRATE CITY THAT WAS SWALLOWED BY THE SEA

Port Royal on the southern coast of Jamaica was claimed by England in 1655 and soon earned the title ‘the richest and wickedest city in the world’. Its location in the middle of the Caribbean made it an ideal base for trade, and buccaneers too were attracted to its large harbour, which was perfect for launching raids on Spanish settlements. Among its most notorious pirates was Henry Morgan, who in a seventeenth-century version of poacher turned gamekeeper was appointed lieutenant-governor of Jamaica in 1674.

By the 1660s most of the 6,500 residents of Port Royal were buccaneers, cut-throats and prostitutes. There was one drinking house for every ten residents, along with all manner of merchants, goldsmiths, artists – and even several places of worship.

Outrageous behaviour was rife in Port Royal. Men paid 500 pieces of eight just to see a common strumpet naked. Some bought a pipe of wine, placed it in the street and then obliged passers-by to drink. Prostitutes with names like No-Conscience Nan, Salt-Beef Peg and Buttock-de-Clink Jenny could hold their own in the rough male company – and amassed fortunes. The most famous was Mary Carleton. A contemporary wrote of her: ‘A stout frigate she was or else she never could have endured so many batteries and assaults… she was as common as a barber’s chair; no sooner was one out, but another was in.’

In its heyday there were around 1,000 residences in Port Royal, many of them large houses with multi-storey brick structures. It was said that the splendour of the finest homes was comparable to those in London.

On the morning of 7 June 1692 Port Royal fell victim to a series of natural disasters, beginning with a massive earthquake. The town was built on the sandy Palisades spit, which was intrinsically unstable, and the western side of the settlement was swallowed by sea, along with all the buildings and inhabitants. Then came an enormous tidal wave which swept away more of the town. When the water subsided only 10 hectares of Port Royal remained. Around 2,000 lost their lives instantly, and a further 3,000 succumbed to injury and disease over the next few weeks.

One astonishing tale of survival concerns Lewis Galdy, a French Huguenot who had settled in Jamaica. The inscription on his tombstone relates: ‘He was swallowed up in the great earthquake… and by the providence of God was by another shock thrown into the sea and miraculously saved by swimming until a boat took him up.’

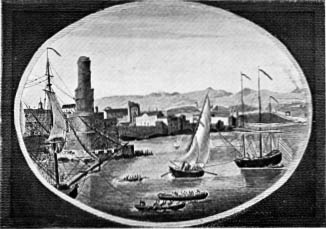

Port Royal, Jamaica

Port Royal, Jamaica.

‘L

IQUID FIRE’

A lightning strike aboard a sailing ship could have horrific consequences – fire, explosion, even the incineration of hapless sailors. Some, who weren’t killed outright, suffered paralysis, terrible burns or blindness. On 21 November 1790 the naval town of Portsmouth in southern England experienced an extraordinary storm. Lightning rolled along the ground ‘like a body of liquid fire’. The 74-gun ship of the line HMS

Elephant

was moored in the harbour and narrowly avoided complete destruction when she was

struck

by the lightning. The maintopmast exploded, but it did not plunge through the quarterdeck, as it was still held by the top ropes.

Lightning could strike anywhere around the world. Because of his command of languages, the Revd. Alexander Scott, who was later to serve as Nelson’s private secretary aboard HMS

Victory

, sometimes undertook duties outside the normal remit of a naval chaplain. In 1802 he was aboard a former French prize

Topaze

in the West Indies, having been sent to St Domingo (now Haiti) to gather intelligence from French officers. While returning from this assignment he was involved in a freak accident.

One evening just after midnight the vessel was struck by lightning during a severe thunderstorm. It split the mizzenmast, killing and wounding 14 men, then descended into the cabin in which Scott was sleeping. He suffered an electric shock and the hooks suspending his hammock melted, flinging him to the ground. Simultaneously the lightning caused an explosion in a cache of small-arms powder stored above him. The resultant blast knocked out several of Scott’s teeth, injured his jaw and affected his hearing and eyesight. For a time he was paralysed on one side of his body. Scott did recover from these injuries, but for the rest of his life he suffered from ‘nerves’.

A study in 1851 of ships in the Royal Navy catalogued the extensive damage caused to the fleet by lightning. One six-year period, from 1809 to 1815, saw 30 ships of the line and 15 frigates disabled. And the merchant marine also suffered; there were vivid reports in the press of the loss of shipping and valuable cargo.