Stars of David (3 page)

Hoffman acknowledges he hasn't given the time to his Judaism that he has to his acting. “I have no one to blame but myself, because I could have learned it,” he says. “Every one of my kids that has had a bar or bat mitzvah, I've had to learn my part phonetically; it's uncomfortable for me.” The family observes all Jewish holidays, though Hoffman noticed his son Max didn't go to synagogue on Yom Kippur in Providence, where, at the time we meet, he's just started Brown University. “We called up Max in Rhode Island, and the first thing he said was âGood Yom Tov.' But he didn't go to services. He just said it to say, âSee, I know what today is.'”

Hoffman is, in fact, planning to drive up to Brown after our breakfast: It's parents' weekend. “My son met a girl who we'll probably meet and her name is Brittany from Mobile, Alabama; I don't think that she's Jewish.” He smiles. “But I don't care.” His cell phone rings: It's Lisa wondering when he's coming home. “Can you give me ten, fifteen minutes?” he asks her. “Okay, my dear. I'll hurry.”

He and Lisa were spotted on camera a couple of nights earlier at the Yankee playoff game against the Boston Red Sox. “Because the New York fans are so devout, if the Yankee pitcher strikes somebody out, everybody stands,” he says. “Then they sit down. And then they stand for the next guy. And the next. They sit down, they stand up, sit down.” He demonstrates. “And at one point, Lisa said, âThis is worse than temple.'”

He says Lisa cares deeply about Jewish tradition, while his connection is more unconscious. “I have very strong feelings that

I am a Jew

.” He punctuates the declaration with his fist. “And particularly, I am a

Russian,

Romanian

Jew. I love herring and vodka; I feel it comes from something in my DNA. I do love these things. And I know I have a strong reaction to any anti-Semitism.”

He recounts a story that was clearly disquieting. It happened when he took his family to the premiere of his film

Outbreak

in Hamburg, Germanyâthe hometown of the film's director, Wolfgang Peterson. “I said to my wife before we left, âAre there any concentration camps around there? Because I think these kids are now finally at the age when they can handle it.' We found out that Bergen-Belsen was forty minutes south. That is where Anne Frank was taken.”

They decided to go the morning after the premiere, and Hoffman took an early walk from the hotel to buy some provisions for the drive. “I heard there was a nearby fancy bakery, and I could get wonderful German pastries and sandwiches. And this place had all these little tables, like this,” he gestures around our restaurant, “and against the wall were these beautiful pastries and the waitresses were very attractive German girls in their striped uniformsâit was as upscale as you would come across. And I'm aware of the fact that no one is coming up to meâbecause when you're a celebrity, you're aware of when you're being recognizedâand they were quite respectful.

“I'm waiting in line to pay, and as I start to pay, a man is sitting at a tableâa man in his twentiesâshort haircut, drinking coffee, well dressed. And he starts yelling, â

Juden!

'” Hoffman pauses. “And the place stops. In my memory, it was like a movie: Suddenly everyone stops like this.” He freezes. “And he repeated it: â

Juden!

'” Hoffman is inhabiting this character now, shouting threateninglyâwith an accent: â

Dostin Hovvman! Juden!

' I remember my brain had to do some work, but I had already done

Merchant

of Venice

in London and I remembered that Shakespeare had used the word in the play. So I made the connection: âOh, that must mean Jew.' It was an extraordinary moment. The irony of hearing this when I'm buying German pastries to go to a concentration camp.

“Finally I turned to this guy and he's just with his coffeeâhe's not drunk. And I'm aware of men in overcoats walking over to him,” Hoffman acts this all out, “and they didn't grab him; he just stood up and they followed him out. And I go back to pay, and there was complete, total denial. All of us. Everyone in the room, including me.” He pantomimes paying his bill. “âThank you very much.' And I walked out in a kind of haze. And of course, when I get a block away, I think of what I should have done. I should have gone over to him and said, âYeahâand?

And? What of it?

'”

Hoffman may have drawn a blank in that instance, but he didn't hesitate years earlier, when there was an artistic dispute as to how his character in

Marathon Man

should handle an anti-Semite. “The big sticking point in

Marathon Man

was the ending,” he explains. “I was called on, as the character, to fire point-blank at the Laurence Olivier character, Dr. Szell [a Nazi dentist], and kill him in that last scene. And I said that I couldn't do it. The screenwriter, William Goldman, was quite upset about it, because first of all, how dare I? He wrote the book. âYour job isn't to rewrite; your job is to play it as written.' I think we had an outdoor meeting in L.A. at the home of the director, John Schlesingerâthere was me, Goldman, and Schlesinger around the tableâand it got nasty. I said, âGo hire someone else'âPacino wanted the partââGo get Al.'

“I remember Goldman saying, âWhy can't you do this? Are you such a Jew?' I said, âNo, but I won't play a Jew who cold-bloodedly kills another human being. I won't become a Nazi to kill a Nazi. I won't demean myself. I don't give a fuck what he did. Even though he tortured me, I won't do it.' And we worked it outâit's in the dialogue. Olivier says”âHoffman does the German accentâ“âYou can't do it, can you? You don't have the guts.' So I don't shoot; he comes at me, there's some wrestling or whatever, and I throw the diamonds at him.

That

I wanted to do. That I dearly loved doing because I believed it. I throw the diamonds at him and they're all falling in the grate around him, he is losing them. And I say, âI'm going to keep throwing them at you until you eat them.' I say, â

Essen

,

essen

' [“Eat, eat”]. Because I didn't mind torturing him; but I wasn't going to shoot him point-blank. I wanted to do what felt like the Jew that's in me. I want him to swallow those fucking diamonds for all those people that he tortured and he killedââEat these fucking diamonds because that's what it was all about to you.'”

He describes how Dr. Szell ultimately falls and impales himself, and then Hoffman's character walks to the Central Park reservoir. “There's a great moment for meâI mean it's just a movie, but neverthelessâthere's this music playing, and there's the fence, and I just go,” he reenacts it, “I wind up my arm and throw this gun over the fence into the reservoir. And I just keep walking. And it's the end of the movie.” He pauses. “And that's important to me: that I didn't shoot him in the end. Being a Jew is not losing your humanity and not losing your soul. That's what they were unable to do when they tried to erase the race; they tried to take the soul away. That was the plan.” He gets choked up and excuses himself to go to the bathroom.

When he returns, neither of us refers to the moment before. He asks if I want to walk with him the few blocks to his home and, as we chat, we end up talking again about the Yankee game he attended a few days ago. “I didn't have any identity onâneither a Yankee hat nor a Red Sox hat,” he says, “and this one woman said, âAre you neutral?' And before I could stop myself, I said, âNo, I'm Jewish.'” He chuckles. “That would never have happened a bunch of years ago. Some part of me wants to advertise it now. Finally.”

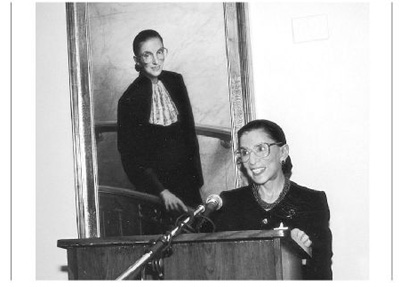

Ruth Bader Ginsburg

JUSTICE RUTH BADER GINSBURG HAS A RUN in her stocking, which, I must admit, puts me at ease. It's my first time in a U.S. Supreme Court Justice's chambersâeven that word, “chambers,” conveys hushed, erudite activityâand it's strangely comforting to see that this tiny woman with the giant intellect gets runs in her hose like the rest of us. “Why don't we just sit here.” She gestures to a couch in her sitting area.

Ginsburg, often described as small and soft-spoken, appears almost miniaturized in her sizable office space, formerly occupied by the late Thurgood Marshall. Dressed all in blackâslacks, blouse, stockings, sandals, a shawl draped around her shouldersâshe looks like a frail Spanish widow rather than one of the nine most powerful jurists in the land.

But it's clear that despite her petite frame, small voice, and a recent battle with colon cancer, Ginsburgâage seventy when we meet, the second woman on the bench in the court's history and its first Jewish member since Abe Fortasâis formidable. She tells one story that illustrates her intrepid style: “My first year here, the court clerk, who is just a very fine fellow, came to me and said, âEvery year we get letters from Orthodox Jews who would like to have a Supreme Court membership certificate that doesn't say

In the year of our Lord

. [She's referring to the certificate lawyers receive when they become members of the Supreme Court bar.] So I said, âI agree; if they don't want that, they shouldn't have it.'

“So I checked to see what the federal courts and circuit courts were doing and discovered, to my horror, that in my thirteen years on the D.C. circuit, the membership certificate has always said

In the year of our Lord

. So I spoke to the chief judges of all the circuits, and some of them had already made the change, others were glad to make the change. Then I came to my Chief and said, âAll the other circuits give people a choice.'” Her “Chief,” William Rehnquist, recommended she raise the issue “in conference” with her fellow justices, which she did. “I won't tell you the name of this particular colleague,” she says, “but when I brought this up and thought it would be a no-brainer, one of my colleagues said, â

The year of our Lord

was good enough for Brandeis, it was good enough for Cardozo, it was good enoughâ' and I said, âStop.

It's not good enough for Ginsburg

.'”

Significant laws have been changed over the last few decades because the status quo wasn't “good enough for Ginsburg.” She is known as a pioneer in the field of antidiscrimination law, a founder of the Women's Rights Project of the American Civil Liberties Union, the first female tenured professor at Columbia University Law School, and the lawyer who argued six women's rights cases before the Supreme Court and won five of them.

She abandoned Judaism because it wasn't “good enough for Ginsburg” either. Its exclusion of women from meaningful rituals was painfully brought home to her at age seventeen, when her mother, Celia Bader, succumbed to cancer a day before Ruth's high school graduation. “When my mother died, the house was

filled

with women; but only men could participate in the minyan [the quorum required for public prayers of mourning].” It didn't matter that the young Ruth had worked hard to be confirmed at Brooklyn's East Midwood Jewish Centerâ“I was one of the few people who took it seriously,” she remarks, or that at thirteen, she'd been the “camp rabbi” at a Jewish summer program. Having a Jewish education counted for nothing at one of the most important moments in her life. “That time was not a good one for me in terms of organized religion,” she says with typical understatement. I ask her to expand on how Judaism made her feel secondary. “It had something to do with being a

girl

. I wasn't trained to be a yeshiva

bucher

.” (She uses the Yiddish word for “boy.”)

Later, she was also turned off by the class system in her family synagogue. “This is something I'll tell you and you know it exists: In many temples, where you sit depends on how much money you give to the shul. And my parents went to the synagogue, Temple Beth El in Belle Harbor, Long Islandâit's right next to Rockaway. When my mother died and my father's [furrier] business went down the drain, he was no longer able to contribute to the temple. And so their tickets for the High Holy Days were now in the

annex

, not in the main temple, although they had been members since the year they married. And I justâthat whole episode was not pleasing to me at all.”

Neither was the time when she tried to enroll her son, James, in Sunday school at Temple Emanu-El on Fifth Avenue in New York City. “The rabbi told me to fill out the application for membership âas though I were my husband,'” she recalls with indignation. “I said, âWell I haven't consulted him; I don't know if he wants to be a member of Temple Emanu-El.'

“The idea was, as a woman, if you were not single, widowed, or divorced, you could not be a member. If you were married, then your husband was the member. I was still teaching at Rutgersâit was 1972. And I remember how annoyed I was. Still, I wanted James to have something of a Jewish education. So I said, âI will make a contribution to the temple that is equivalent to the membership, if you will allow my child to attend Sunday school.'”

I ask her if these bouts with sexism were what kept her from embracing Jewish observance. Again she's not expansive. “Yes,” she answers softly. “Yes.”

Despite giving up synagogue attendance, Sabbath candle-lighting, and fasting on Yom Kippur, Ginsburg did go to her husband's parents' home for Passovers. “That was always a great time for the children,” she says. “I think even more for my children than it was for me.” Her husband, Martin Ginsburg, a respected tax lawyer and an accomplished cook, occasionally dabbled in Jewish ethnic cuisine. “In his very early days he made his mother's chopped liver,” she says with a smile.

Her children were bored with Sunday school, and she didn't urge them to stick it out. “James was not bar mitzvahed,” she says of her younger son, “and that was his choice. He didn't want to do the studying. We were living in California at that timeâwe were at Stanford [where she was a Fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences]. James did not like the Sunday school there, and I didn't want to have one more issue in his life.”

Her daughter, Jane, ducked Sunday school more cannily. “She made a deal with us.” Ginsburg smiles. “We were then going to a much nicer Sunday school at Shaaray Tefilah on East Seventy-ninth Street in New York City, but Jane didn't like it very much. She is ten and a half years older than her brother. One Sunday morning, when he was an infant, I overslept; she took care of him and didn't go to Sunday school. And I was so glad that she did such a good job. So she said that she would make a deal with us: If she didn't have to go to Sunday school anymore, she would take care of James every Sunday morning. That was an offer I could hardly refuse. So that's when she stopped.

“But Jane became very Jewish again when she married a Catholic boy,” Ginsburg continues. “First, she wanted to have a rabbi reassure her that even if her children were baptizedâwhich they were because it was important to my son-in-law's Italian-Catholic motherâthat it could still be a Jewish baby. And I thought that would be easy.” Ginsburg shakes her neatly chignoned head. “But it was very, very hard to find a rabbi who would say that. Ab [Abner] Mikva was my chief judge on the D.C. Circuit Court. His daughter is a rabbi and she said, âNo, I won't tell her that.'”

I remark that this must have been very upsetting. “Yes,” Ginsburg says with a nod, “but I said to Jane, âThis woman [the Italian-Catholic mother-in-law] is thinking that if her grandchild isn't baptized,

this child's soul will

never go to heaven

. So it's just to put her at ease.'”

Did it matter to Justice Ginsburg that her children marry Jews? “No. Jane is married to a very fine man who is perfect for her. And she had anticipated all kinds of difficulties that didn't arise. There was a question of Sunday school and I said, âWait till Georgeâmy son-in-lawâfinds the church that he is going to enroll Paul and Clara in.' And he never didâto this day he hasn't. My granddaughter, who will be thirteen in October, is this summerâfor the second timeâgoing to a Hadassah-run camp on the French side of Lake Geneva. So now she knows more about Judaism than I have forgotten.”

Ginsburg seems comforted by a sense that her grandchildren know what's at the heart of their birthright. “I think they have enough of an understanding that, when you are a Jew, the world will look at you that way; and this is a heritage that you can be very proud of. That this small band of people have survived such perils over the centuries. And that the Jews love learning, they're the people of the book. So it's a heritage to be proud of. And then, too, it's something that you can't escape because the world won't let you; so it's a good thing that you can be proud of it.”

So what does it mean to be Jewish without rituals? “Think of how many prominent people in different fields identify themselves proudly as Jews but don't take part in the rituals,” Ginsburg replies. She adds that even without observance, being Jewish still matters greatly to her. “I'll show you one symbol of that which is here”âshe gets upâ“if you come.” We walk across her office, which is surprisingly ordinaryâno dark paneled walls, inlaid desks, or library lamps. It looks more like a civil service office with gray carpeting, tan puffy leather chairs, and a round glass table (with a stuffed Jiminy Cricket doll sitting on top). The only clue to Ginsburg's personality is the profusion of family photos propped on her bookshelvesâpictures of son, James, who produces classical music recordings from Chicago; daughter, Jane, who teaches literary and artistic property law at Columbia; the two grandchildren; and of course, the requisite Ginsburg-with-Presidents SeriesâCarter, Clinton, Bush Sr., George W.

She guides me to her main office door, where a gold mezuzah is nailed prominently to its frame. “At Christmas around here, every door has a wreath,” she explains. “I received this mezuzah from the Shulamith School for Girls in Brooklyn, and it's a way of saying, âThis is my space, and please don't put a wreath on

this

door.'”

Her barometer for religious insensitivity rises not just around Christmastime, but at the beginning of each court term. “Before every session, there's a Red Mass [in a Catholic Church],” she says. “And the justices get invitations from the cardinal to attend that. And not allâbut a good numberâof the justices show up every year. I went one year and I will never go again, because this sermon was outrageously anti-abortion. Even the Scaliasâalthough they're very much of that persuasionâwere embarrassed for me.” (She and Justice Antonin Scalia are close friends who have celebrated many New Year's Eves together, despite their profound ideological differences.)

Clearly, Ginsburg takes symbolism seriously. Though others might view it as nitpicking, she's always deemed it worth her effort and prestige to challenge small inequities, in addition to working toward large-scale reform. Thus, the changed language in the lawyer's certificate, the jettisoned wreaths, the boycotted Red Mass, and most recently the blacked-out First Monday in October: “We are not sitting on the first Monday in October this year and we will not sit on

any

first Monday that coincides with Yom Kippur,” she says proudly. “Now, this is the

first year

that is happening. The first time Yom Kippur came up, it was an ad hoc decisionâwe were not going to sit that Monday. But now, this is the way it's going to be from now on.” Having her comrade Jew on the court, Stephen Breyer, lobbying alongside her was crucial, she says. “In this great Yom Kippur controversy, it helped very much that there were two of us.”