Stars of David (2 page)

I also realized I'd have to work harder to keep my own family Jewish than I would if I'd just married another Jew. I wanted the Jewishness to just be there: in my children's faces, in their food, in their celebrations. I wasn't sure enough of my own faith and history to be confident I could effectively pass it on.

My religious identity used to be informed entirely by my mother: She made the holidays sparkle, she made me feel there was a privilege and weight to being Jewish, she made me feel lazy for not doing more to understand it. But now I'm wading in in my own way, on my own time. And this book felt like one step in that direction.

The specificity of each person's Jewish chronicle was unexpected. The fact that Mike Nichols still feels, at his core, like a refugee; that Edgar Bronfman Jr. initially rejected Judaism because he rejected his father; that Beverly Sills felt uncomfortable enrolling her deaf Jewish child in a Catholic school, chosen because it specialized in educating deaf children; that Alan Dershowitz gave up his Orthodox observance because he couldn't defend it to his children. That Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg spurned Jewish ritual because of its sexism; that Barry Levinson believes Jewish Hollywood executives abandoned his film

Liberty Heights

because it was “too Jewish”; that Mike Wallaceâlong labeled a “self-hating” Jew because of his coverage of the Middle Eastârecites the Shema, Judaism's most hallowed prayer, every night; that Natalie Portman feels ashamed of her Long Island hometown's materialistic Jewish values; that Kati Marton never quite forgave her parents for hiding the fact that she was Jewish; that Kenneth Cole has misgivings about agreeing to raise his children in his wife's Catholic faith. My conversation with Leon Wieseltier upended my approach to Judaism because he challenged my justifications for remaining uninformed about it.

These portraits are micro snapshots: They are private, often boldly candid, idiosyncratic, scattershot, impressionistic. They are not exhaustive, they do not purport to answer the macro questions about assimilation, anti-Semitism, or Jewish continuity. They are highly personal stories from people we feel we kind of knowâstories that hopefully peel back a new layer. I was not investigating how many powerful Americans are Jewish, or how much power powerful American Jews have; what interests me is how Jewish those powerful Jews feel they are.

I intentionally chose not to underscore the commonalities among these voices because I believe they will reverberate differently for each reader. Recurring themes, including the tendency to abandon childhood rituals, the thorny questions of intermarriage, the staunch pride in history, and the ambivalence about Israel, will undoubtedly feel familiar depending on one's experience.

I understand the temptation to turn first to chapters about the people one already admires, but some of the best nuggets lie among the least known. Even if you've never read a Jerome Groopman piece in

The New

Yorker

, it's intriguing to hear this doctor's views on the clash between science and faith. Even if you're not a

Star Trek

fan, it may surprise you to learn how Leonard Nimoy based Spock's Vulcan greeting on a rabbinic blessing. Even if you disagree with every word “Dr. Laura” has ever said on the air, you may feel a pang of sympathy for her once you read about the vitriol she endured from other Jews after her conversion to Judaism.

We are living in a period of heightened religious awareness. Our political leaders cite biblical verses and claim to act in the name of God. Popular magazines run cover stories on spirituality. From Chechnya to Iraq, from Rwanda to Bosnia, we've seen how ethnic loyalties can bring out the worst in people. What I've attempted to probe in this book is how those Jews who are major players on the stages of American politics, sports, business, and culture feel about their Jewish identity and how it plays out in their daily lives. Just as these public Jews have entered our collective consciousness through their outsized accomplishments and celebrity, we can find parts of ourselves in their honest, intimate personal stories.

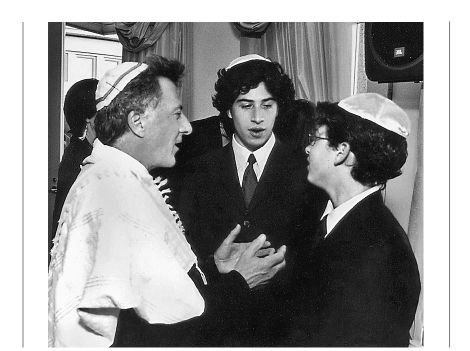

Dustin Hoffman

ALEX BERLINER © BERLINER STUDIO/BE IMAGES

DUSTIN HOFFMAN VIVIDLY RECALLS ONE AFTERNOON, sitting in his apartment on 11th Street in New York City, talking on the phone to Mike Nichols. The director was trying to convince Hoffman to audition for the part of Benjamin Braddock in

The Graduate

. “Mike was asking, âWhat do you mean you don't think you're right for the part?'” Hoffman says. “âBecause you're Jewish?' I said, âYeah.' Mike said, âBut don't you think the character is Jewish

inside

?'” Hoffman reminds me that Braddock was originally written as a thoroughbred WASP. “The guy's name is Benjamin

Braddock

ânot Bratowski,” Hoffman says with a smile. “He's a track star, debating team. Nichols tested everybody for the partâI think he tested Redford, who visually was the prototype of this character.”

Hoffman finally agreed to fly to L.A. to audition. “That day was a torturous day for all of us,” he says. “I think I was three hours in the makeup chair under the lights. And Mike was saying with his usual wry humor, âWhat can we do about his nose?' Or, âHe looks like he has one eyebrow'; and they plucked in between my eyebrows. Dear Mike, who was, on the one hand, extremely courageous to cast me, in the end was at the same time aware that I looked nothing like what the part called for.” Hoffman laughs.

We're having breakfast in a Columbus Avenue restaurant near his apartment in New York City. He arrives in buoyant spirits, dressed in jeans, white T-shirt, and blue blazer. Right away he befriends the waitressâ“Where did you grow up?” She turns out to be from his childhood neighborhood in Los Angeles: Orlando Street. “Oh my God,” he says, “I grew up on Flores!”

He orders very specific “loose” scrambled egg whites with one yoke thrown in, plus onions, salsa, and garlic. “Not too dry, no milk, no butter; a little olive oil.” Hoffman shakes his head when I order my omelet. “Omelets aren't the best way to go,” he advises me. “Scrambled is tastier. But you go ahead with your omelet.”

Back to 1967: Nichols, who had seen Hoffman in an off-Broadway play, invited him to California to audition: “I flew out to L.A. with very little notice, and of course hadn't slept,” says Hoffman. “I was very nervous. And in my memory, it was an eight-page or ten-page scene in the bedroom, and of course I kept fucking it up. I distinctly remember Mike taking me aside and saying, âJust relax; you're so nervous. Have you ever done a screen test before?' I said, âNo.' He said, âIt's

nothing

; these are just crew people here; you're not on a stage. This is just film; no one's going to see it. This isn't going into theaters.' And I nodded and I was so thankful that he was trying to soften me; but then he put his hand out to shake mine, and his hand was so sweaty that my hand slipped out of it.

Now

I was terrified. Because I knew, â

That man is as scared as I am

.'

“I felt, from my subjective point of view, that the whole crew was wondering, âWhy is this ugly little Jew even trying out for this part called Benjamin Braddock?' I looked for a Jewish face in the film crew, but I don't think I sensed one Jew. It was the culmination of everything I had ever feared and dreaded about Aunt Pearl.” He's referring to his Aunt Pearl, who, upon learning that “Dusty” wanted to become an actor, remarked: “âYou can't be an actor; you're too ugly.'” “It was like a banner,” Hoffman continues: “â

Aunt Pearl was right!

' She'd warned me.”

Hoffman reaches into the bread basket to break off small chips of a baguette. “It was probably one of the more courageous pieces of casting any director has done in the history of American movies,” he continues. “And an act of courage is sometimes accompanied by a great deal of fear.”

Obviously the film went on to become a classic and made Hoffman a star. But even after becoming a Hollywood icon, with memorable roles in such films as

Midnight Cowboy, Marathon Man, Kramer vs. Kramer, Tootsie

, and

Rainman

, at the age of sixty-eight, Hoffman says he's still being “miscast”: “Someone told me about a review of this movie I did,

Runaway Jury

, which indicated that I was miscast because the part was a Southern gentleman lawyer. Which must mean to that critic, âHe shouldn't be Jewish.' The unconscious racism is extraordinaryâas if there are no Southern gentlemen Jews. So he implied I was miscast. And I mentioned that to my wife and she said, âWell, you've always been miscast.' And she's right. The truth is that you've got two hundred million people in this country and I don't know the number of Jewsâare there six or seven million? [An estimated 5.7 million.] I think there's thirteen million in the world [13.9]. So in a sense, we're miscast by definition, aren't we? That's what a minority is: It's a piece of miscasting by God.”

Hoffman grew up unreligiousâ“My father later told me he was an atheist,” he says of Harvey Hoffman, a furniture designer. Though they celebrated Christmas, one year he decided to make a “Hanukkah bush” instead. “About the time I realized we were Jews, maybe when I was about ten, I went to the delicatessen and ordered bagels and draped them around the tree.”

But when it came to Hoffman's neighborhood friends, something told him he should deny his Jewishness. “It was so traumatic to me, before puberty, realizing that Jews were something that

people didn't like

. I have a

vivid

recollectionâliterally

sensory

feelingâof the number of times people would say to me (whether they were adults or kids), âWhat are you?'” Hoffman pauses. “It was like it went right through me.” He twists his fists into his belly. “It was like a warning shockâpainful. And I

lied

my way through each instance of that kind of questioning. So here would be the dialogue: You ask me, âWhat are you?'”

POGREBIN: “What are you?”

HOFFMAN: “American.”

He gives me direction: “Now you press.”

POGREBIN: “What kind of American?”

HOFFMAN: “Just American.”

POGREBIN: “What are your parents?”

HOFFMAN: “Americanâfrom Chicago.”

More direction: “Keep pressingâbecause they would. They'd ask, âWhat

religion

are you?' And I'd play dumb.”

So he knew that being Jewish was something to hide? “Oh God, yes,” he replies immediately. “I didn't want the pain of it. I didn't want the derision. I didn't come from some tough New York community where I'd say, âI'm Jewishâyou want to make something out of it?' There was an insidious anti-Semitism in Los Angeles.”

It's one of the reasons he was impatient to move to New York, which he did, at age twenty-one. “I grew up always wanting to live in New York, even though I'd never been here. And what's interesting is that all people ever said to me and still say is, âOh, I always assumed you were from New York!' Even now, if you look Jewish, you're from New York. I didn't know that most of the Jews in America live in New York. But I did know it inside. I flew to New York to study acting in 1958; I took a bus from the airport terminal to New York City and they let me off on Second Avenue. It was summer, it was hot, and I walked out of the bus, and I saw a guy urinating on the tire of a car, and I said, âI'm home.'” He smiles. “The guy pissing on the tire must have represented to me the antithesis of white-bread Los Angeles: New York City was the truth. It was a town that had not had a face-lift, in a senseâthat had not had a nose job.”

Despite the city's ethnic embrace, when it came to open casting calls, Hoffman learned quickly into which category he fell. “Character actor,” he says with a grin. “The word âcharacter' had a hidden meaning: It meant âethnic.' âEthnic' means nose. It meant ânot as good looking as the ingenue or the leading man or leading woman.' We were the funny-looking ones.”

I ask whether it frustrated himâbeing pigeonholed. “Sure. But everything frustrates you when you're not working.” He pauses. “I think I just gave you the glib answer. I think the non-glib answer would be how quickly you accept the stereotype that's been foisted on you: âThey're right; I'm ugly.' You learn that early, before you even think about acting. You learn that in junior high school.”

I assume that changed for him when he became a bona fide movie star whom many considered adorable. “I still don't feel that, by the way.” He shakes his head. One's self-image, he maintains, is indelibly shaped in adolescence. “You're really stuck with those first few years,” he says. “That's what stays with you. It takes a lot of therapy to break through that.”

What about all the women who must have thrown themselves at him at the height of his fame? “It doesn't matter,” he insists. “If you're smart, you know you're interchangeable. It's like people coming up and asking for your autograph; they'll ask any celebrity.” He also says he realized after a while that the shiksa conquest has little staying power. “The cliché from the male point of viewâwhich is another interviewâis the number of times we men in our youth would talk about girls that we had bedded down. And there was often the comment, âWhat a waste; I mean here she isâa model, gorgeousâand she's just a lox.'” He laughs. “I mean, you learn. That outward stereotype only goes so far.”

But the short Jewish guy with the nose did choose the trophy wife for his first marriage. “The first wife was Irish Catholic, five-foot-ten, ballet dancer.” He smiles. “I don't want to discredit this ex-wife, but the grandmother of my current and lasting wife, Lisa, her grandmother Blanche once referred to my first wife as,” Hoffman dons a husky voice, “âHe married a bone structure!'” He laughs. “I mean, that was the prize.”

I wonder if he himself ever thought about changing his appearance? “No, but my mother asked me to. When I was a teenager, when she got

her

nose job, I remember she wanted me to get one, too. She said I would be happier.”

I tell him it's probably a good thing he didn't. “Oh but I did,” he jests. “You should have seen it before!”

He says his first set of in-lawsâfrom Chappaqua, New Yorkâweren't thrilled about their daughter's choice in husbands. “I think there was a certain amount of ambivalence on her parents' part that she was marrying a Jewish guy. I don't think they were tickled about me before I became famous and I think they were a little more tolerant afterwards.”

Didn't he feel some vindication once he became prominentâa kind of “I showed them” to his in-laws, to Aunt Pearl, and to all the casting directors who'd once dismissed him? “I can't say yes because I don't remember that feeling. On the contrary, I tried my hardest after

The Graduate

to defame myself. I was

sent

scripts for the first time, and I just kept saying, âno, no, no.' I did not want to be a part of this party joke that I was now a leading man.” Hoffman is almost never still; he keeps tearing at the baguette, adjusting the sugar packets, the flatware. “None of this is simple,” he says.

His second and current wife, Lisa Gottsegen (“We just celebrated twenty-three years,” he announces proudly), took him on a more Jewish path. “My wife changed everything,” he says. “Two sons bar mitzvahed, two daughters bat mitzvahed.” They have four children together (he also has two children from his first marriage, one of whom was a stepdaughter). Their family rabbi, Mordechai Finley, who Hoffman describes as “a red-headed Irishman with a ponytail”âis someone to whom Hoffman speaks candidly about his misgivings about faith. “I said, âMordechai, can I tell you the truth? I used to live on East Sixty-second Streetâyears ago, when I was still married to my first wifeâand there was the Rock Church (it's still there) across the street. And I'd hear the singing and the clapping and I loved it.' I said to Mordechai, âI always wanted synagogue to be like that.'”