Stars of David (31 page)

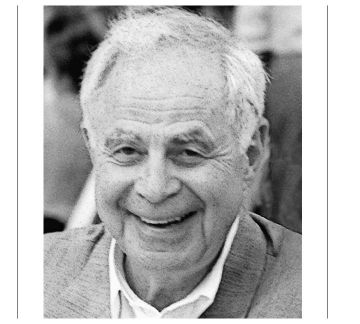

Max Frankel

MAX FRANKEL PHOTOGRAPHED BY BILL CUNNINGHAM/NY TIMES

DESPITE THE FACT that Max Frankel, former executive editor of the

New York Times

, barely escaped Hitler's Germany at the age of eight; despite his clear recollection of Nazi guards terrorizing his father's dry goods store and preventing his familyâand so many othersâfrom going to the movies, sitting in a coffeehouse, or swimming at the public beach, Frankel, now seventy-five, harbors no bitterness. “The only explanation I have for that is that it's a survival mechanism,” he says, sitting in the Upper West Side apartment he shares with his wife of sixteen years,

Times

Metro columnist Joyce Purnick. “My survival mechanism is a kind of cockeyed optimism. It's not a lack of caring; it's âI'm bigger than they. I can outlast this.'” He traces his lack of vengeance to his mother, Mary. “My father was more the angry type.” But he wasn't around to influence young Max. “He was gone for a long time.”

Eight years, to be exact. Frankel's family was arrestedâalong with other Jews of Polish originâin late October 1938, and they were taken to Poland. Max and his mother got permission to return to Germany to pick up visas for the United States, but Max's father, Jakob, who was supposed to join them two months later, was arrested in Poland by the Soviets. He ended up being sent to a Siberian labor camp, where he almost died. After the war, in 1946âeight years after he'd last seen his wife and sonâhe managed to join his family in New York.

During the interim, the young Max endeavored to become an American as quickly and completely as possible. “Assimilation as a refugee kid was a total escape from the unpleasantness of the past,” Frankel says, “and total immersion in the uncritical acceptance of everything American. This was a great country: You could breathe, you had total opportunity. I remember fiercely debating my elders in the neighborhood up in Washington Heights who were complaining about this or that in this country, and I just wouldn't hear of it. I never even realized how far my assimilationist tendencies went; I mean, I wouldn't speak German back to my mother, even though she would talk to me in German because she wanted me to be able to communicate with my father when he eventually joined us. And I never even dated a German girlâa refugee girl. I was hell-bent to get out of the neighborhoodâto go to a different school than all the neighborhood kids. Now that's assimilation with a vengeance.”

Frankel sits in an easy chair with his arms folded and the remains of yesterday's February blizzard visible behind him between wooden Venetian blinds. His carpeted study is muted except for the computer's hum and its occasional chime signaling an incoming e-mail. Frankel is wearing Mephisto sandals over gray socks.

I wonder if his mother felt wounded by his hunger to assimilate. “I think my father found it harder to accept,” he says. “My lack of dependence on his counsel.”

Still, he had made a pact with his mother that when his father finally joined them, they would let him reassume his role as head of the family. “It rankled,” Frankel recalls. “He and I had our blowups.” But the son sympathized with the father's displacement. “I understood why my mother wanted it that way, how hard it was to reinsert him into the family.”

Frankel's childhoodâabsorbing hatred so young, being without siblings and for years without his fatherâclearly accounts for his early independence and his lack of sentimentality. “I not only learned to be alone as a very young kid, but in one sense, I invented my own cheering section. I'm sure it made me fiercely competitive. My form of retribution and vengeance was the feeling I had when I finally returned to my hometown in Germany with an American passport: âTake that, you bastards.'”

Still, there was never generalized hatred. “To me there were no such things as âGermans': There were Bad Germans and Good Germans. I only saw them as people, trapped in a ghastly system.” When Frankel hears people write off an entire population because of the Holocaust, he has no patience for it. “I consider it stupid and unthinking and ultimately a lack of experience,” he says in a clipped tone. “You see it repeated in people now thinking that there's something unique or special about Muslims or Arabs.

“I have a Hobbesian view of humanity,” he goes on. “I think our worst instincts are terrible and the beauty of our Jewish ancestry is that they invented the concept of law to inhibit the worst human instincts.” It is that contribution that moves Frankel. “Jews codified a set of values and laws, synthesized in the Ten Commandments, that form the roots of our culture as I see it,” he says. “There is ultimately no way of explaining the American Declaration of Independence, the Bill of Rights, and the concept of the Constitutionâno way of divorcing that from the ethical precepts that are embodied in ancient Jewish religion. They were

preserved

in Christianity. But it is the concept of

law

, as opposed to

love

âwhich is the Christian contribution, in my viewâwhich permits the peace. It's romantic and it's lovely to love one another, but my observation is that we don't. And so we better just restrain those other instincts with laws. And that's an incredible contribution to thought. So if I have pride as a Jew, it's because of that contribution. But our own people have betrayed it so often that I cannot claim any other kind of superiority.”

When have Jews betrayed it? “Most obviously in Israel today. I think we're tone-deaf to the needs of other people for law, order, stability, and equal rights. I just don't think Jews are any better than any other group; that's all I'm saying.”

Frankel knows firsthand why Jews needed Israel as a refuge, but finds great fault with the country's end result. “I'm beginning to wonder now whether the imperative of those years, and of that generationâof those survivors of Hitlerâwhether it was ultimately wise to have yielded to that need and to create this artificial state and implant it in the midst of such hostility. I was all for it, because these people had no place to go. And the whole notion that we could finally write our own passport and have our own flag and our own jails for our own criminals I thought was crucial. In this horrible world, I guess it is still crucial and still important. But nationalism is also the curse of our time. And the Israelis are proving the twosidedness of that proposition.

“So yes, I have an emotional feeling toward Israel, the extreme of which I felt when that business was going on in the U.N. about defining Zionism as racism. I personally stoppedâeven broke offârelations with a couple of diplomats that I knew whom I had fond relations with, and who, out of a sense of loyalty to their own governments, were supporting that movement. But I really felt it so offensive, that if they insisted on defending it in private to me, I said, âI don't want to have anything to do with it anymore.' Not because I was a Zionist, but because I felt they were just defining the people who had found a haven in Israel as inhuman.”

I want to clarify his comments, because readers may take from them that he fundamentally questions whether the establishment of the state of Israel was a mistake. “History is history,” he says. “Maybe Texas shouldn't belong to the United States either and maybe the Mexicans have a right to keep on complaining about it. And maybe half of Poland shouldn't have been moved into Russia and half of Germany back into Germany; no, I don't play those games. I'm a hardheaded realist. What is, is, and every people has to deal with the hand they're dealt. I just think that Israel happened as an accidental response to Hitler. It would have never become what it became and Zionism would have never succeeded if it hadn't been for the guilt of the rest of the world. I understand that. So in that purely emotional sense, I understand the resentment of some of the Palestinians and other Arabs. But, tough. They have enough territory in which to make do. And maybe Puerto Rico should have been, like Cuba, independent. But it isn't. I have no patience for people who want to undo history; it can't be done.”

Frankel's opinions on Israel roiled some readers when he wrote for the

Times

editorial page and later became its editor. “The attacks didn't sting,” he says, “I just felt, âHow stupid these people were,' saying that I didn't know who Hitler was, that I was a self-hating Jew. That just proved the total incoherence and the stupidity.” He corrects himself: “It's wrong to call people stupid; they weren't stupid, they were just unthinking.”

I tell him that Mike Wallace and Don Hewitt related a similar story: They were assailed as being lesser Jews when their

60 Minutes

reports were perceived as anti-Israel. He explains why those journalists and he as well were considered traitors. “The first rule of the shtetl is you don't let the goyim see you divided,” Frankel says. “You fight like hell among yourselves, but you must present a united front to the rest of the world.”

I ask him if his willingness to be a Jew who criticized Israel affected his Jewish friendships. “I wouldn't say that, no. But it's probably kept me away from certain circles. You know, we sent our kids to Hebrew school, but I protested vigorously when the school was being corralled into protest marches downtown on various political issues. I not only wouldn't let the kids go, but I really argued strenuously at the synagogue. Because it was âIsrael all for one; they can do no wrong.' It was propagandizing the kids in a way that I thought harmful. It made them unthinking Jews, which I used to think was something of a contradiction, but it isn't. Regarding my friendships, I guess it's fair to say that I was never attracted to the all-out Zionist circles. So it's not only that it disrupted friendships, I never gave myself the opportunity for friendship.”

Would he say his closest friends are Jewish? Frankel pauses, clearly running the names through his head. “Yeah, they are,” he replies. He doesn't see that as significant. “I think it's just a function of New York and the media.”

Frankel's dispassion when it comes to Israel and to German guilt carries over to his lack of spirituality. “I can't pray,” he says simply. “After my bar mitzvah, I went to synagogue for my parents' sake,” he says, “and then I went for my first wife's sake [Tobi Frankel died of brain cancer in 1987], and then for my children's sake, because I did want them to be exposed.” His son David is a film and television director; his daughter, Margot, a graphic designer; and his son Jon a former network correspondent who now has his own business making video biographies; all three have children of their own. “I couldn't very well push my kidsâI was a bad enough example at home for being unreligious and got hell for thatâso I went along with it and tolerated it. I'd go to temple once a year, and we'd have good seders. We did these things out of kind of a feel-good emotional sense of identification; âkeep the candle in the window' kind of thing. But at synagogue per se, I do not find it psychologically important. So I don't pray.”

He did, however, give his children a Jewish education, and hopes they do the same for theirs. “I wanted my kids to be able to feel emotionally that they belong to this diverse group of people known as Jews. And if I suddenly had to, God forbid, care for my grandchildren, I would do the same thing. I think it gives them a sense of belonging and the knowledge to understand what it is they're rejecting, without hating themselves.

“I still think they need that feeling of âwhere do I come from and what is it that I'm saying

no

to in this society'?

I

at least know what I'm

not

doing. The fact that I can walk into any synagogue anywhere in the world and open the book and know where they are and what they're doing and why they're doing it, even though it doesn't touch me emotionally at all, I think that makes me a better rejecter of religion than if I were somehow on the outside looking in.”