Stars of David (6 page)

“There's an extraordinary resonance in the journey that the Jewish people have endured. It is prophesied in the Torah that âThe Jews over time will be scattered among nations, will always be few in number,' and our prophets wrote that we will always be âa light unto nations.' . . . The prophecy as to the breadth of the Jewish nation has so far proven to be true, we know that the Jewish nation is the only one to have experienced and survived in exile twice (the second time for almost two thousand years), and few would doubt that the Jewish world (however small it remains, as dispersed as we know it is) has also had an extraordinarily positive impact on the morality of the entire civilized world.

“We've survived this long despite so much adversity and there is an immense depth in the lessons we have learned along the way. My hope individually is that my daughters can get as much as there is to offer from that. And our hope collectively, Maria and I, is that in the end, they will be thoroughly enriched by both faiths.”

I ask him what he thinks his children will say, down the line, if someone asks if they're Jewish: “I hope they'll say . . .” He pauses. “I mean right now they define themselves as being religiously Christianâbecause the Jews and the Christians all believe that the child is affiliated in the womb from the mother, and so, unless Maria's going to convert, which isn't going to happen . . .” He begins again: “My hope is that they'll make clear that there is a part of them that is Jewish. And there

is

. And to the degree it positively manifests itself in their lives, the more comfortable they will be embracing it.”

He is also conscious of steering them away from Jewish stereotypes, which he fears can sometimes be self-inflicted. “I hate the term JAP. Hate it. But I think I know how it's fueled. We tend to want to give our children everything. We want to give everything we had plus everything we didn't have. And in the end, we probably do indulge them and enable them to have a sense of entitlement.”

Though Cole has spent the last decade exploring his heritage, he hasn't wanted his Jewishness to classify him. “I rarely accept invitations to speak or make an appearance somewhere because I'm Jewish. I just haven't done that. I've accepted invitations because of what I do and why. And the fact is I'm a Jewish person doing it, for which I'm proud, but I'm reluctant to make the case that the reason I'm doing it is because I'm Jewish.”

Is he comfortable being an emblem of success for “The Jews” in general? “I've been uncomfortable doing that,” he acknowledges. “I don't know if the success I've had (to the degree you call it that) is because I'm Jewish, or despite the fact. Also, it doesn't feel right for anyone to just assume that mantle. One should keep in mind that if they do choose that course, they might at one point stumble, or even worse, fall (maybe to get up again or maybe not), and then what?” He then qualifies this: “I'm certainly not quiet about being Jewish.”

Ever since his third trip to Israel, however, he has been “coming out”âor inching outâas a Zionist. In 2002 he returned with his brother-in-law, Andrew Cuomo. “It was a day after the Passover massacre [when nineteen Israelis were gunned down at a communal seder], and I got a call from Andrew, who was running for governor of New York. He said, âLet's go to Israel tomorrow.' Just when the State Department was putting out an announcement saying that all unnecessary government officials should return home and a warning to all Americans to stay away.”

Cole says the people close to him told him not to go. “

Nobody

was supportive of this trip,” he says. “They said, âAndrew has to go, it's good for him politically, but you're a lunatic, you're out of your mind, who do you think you are?' But I thought this was an important time and that the effort we could make at that moment would have so much more significance than the same gesture made at another time. Israel's existence seemed as much in jeopardy as it had ever been; there was this little island of about five million Jews amongst a nation of six million people, surrounded by over a billion Muslims in the world, many of whom were united by a single common goal: the annihilation of the state of Israel and the Jewish people.

“What is frighteningly noteworthy is that somehow over the last several years, Israel, in the world's eye, has gone from being viewed as the vulnerable David to the intrusive and aggressive Goliath. Upon our arrival in Tel Aviv, I should add, beyond even our greatest expectations, we were embraced and given access typically reserved for heads of state.”

It appears Cole has gone from dipping a toe into Israeli politics to an ankle-high commitment. “It can't be just about writing checks,” he clarifies. “I wouldn't join a club once because part of the ritual was that every year you had to make a contribution to the UJA. Not that I didn't support them, I did, but I didn't feel that it should be an obligation. And I believe sometimes that just writing a check (although often necessary) is too easy, and is often the course of least resistance. There are so many resources we all have that can yield much more value.

“I do believe strongly in many fundamental Jewish principles: the importance of

tzedakah

[charity], for instance, which we are taught is an obligation and a responsibility, and learn later is actually a blessing and a privilege. And

tikkun olam

[healing or repairing the world], which means that our job on this planet is to finish the process of creation; God gave us what's here and our job is to finish it in a morally just way. But I don't necessarily believe that one has to do it with a yarmulke on.”

He uses his fashion ads instead. A fall 2002 campaign, for instance, featured a newsstand scene with a man holding a newspaper whose headline trumpeted “Holy War.” The ad copy:

“Mideast peace is the must-have for fall.”

I close our discussion by probing a little further into how he feels about raising his children in his wife's faith. “Under the circumstances, it is the right thing to do,” he reiterates. “But it's probably the hardest thing in my life that I have had to come to terms with and it just doesn't seem to get any easier. As hard as it is for me today, however, I believe more than I ever did how important it is for them. To have a sense of faith, so that when they put their heads on their pillows at night, they never feel alone. I have accepted the responsibility that I have to teach them more about that special side of them that is Jewish. And as a result, I've learned more myself over the years and probably taught them more than I was taught more formally when I was their age.”

As Cole escorts me out, the dog, Bernie, runs up in a good-bye of sorts. “I should add that a significant concession was made in this house.” Cole smiles. “Maria, after much consideration, agreed to allow me to at least raise the dog Jewish.”

Beverly Sills

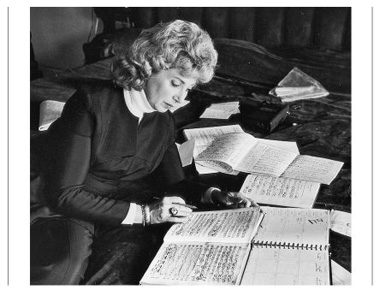

BEVERLY SILLS PHOTOGRAPHED IN 1974 BY JILL KREMENTZ

BEVERLY SILLS, possibly the most famous soprano in the world, has dropped crumbs of ruggelach on the front of her dress and it's my fault. I brought the small Jewish pastries to get us in the mood. “Oh God,” she says, taking another bite, “no self-control.”

Sills's office at the Metropolitan Opera, where she was chairwoman when we met, is not especially large or personally appointed, but when she starts to talk about her Jewish past, I feel immediately like I'm in my Great Aunt Belle's home (in fact, Sills's real name

is

Belle). Sills is so unaffected and warm, there are no airs of the diva. As we talk, I forget that she's the woman who was once dubbed “America's Queen of Opera”âthe highest-paid opera singer of her dayâwho received the Presidential Medal of Freedom and who has famous friends like the Kissingers, who she says often invite her to their Sunday hot dog suppers. Her smile is big, her laugh is deep, and she's eating a Zabar's ruggelach with proper appreciation.

“My mother's father was a political refugee.” Sills explains he had been sent, as a young man, from Russia to Paris to study electrical engineering, and was radicalized there by the writings of Eugene V. Debs. “He returned home a Socialistâa great embarrassment to the familyâand was asked to leave. He was very hotheaded, spoke seven languages, a very attractive man. And he left behind my grandmother with three little girls and pregnant with a fourth. The oldest of the three little girls was my mother.” Debs helped bring her grandfather to Brooklyn, and months later, the rest of the family followed.

On her father's side, her Grandma Fanny was born in Romania and was widowed three times. “She had

fifteen

children,” she marvels, “and she came here with all fifteen. The next to the youngest was my dad.” Grandma Fanny was wealthy and also lived in Brooklyn, albeit in a bigger house on Eastern Parkway. “She wore a black dress all her life,” Sills says with a chuckle. “We'd say to her, âWhy do you always wear black, Grandma?' And she said, âI'm in mourning.' And we'd say, âFor whom?' And she'd say, âWhatever.'” Another deep laugh.

Fanny created massive Passover seders, which Sills recalls as wonderfully chaotic. “There could be sixty people and she did all the cooking. She made all these doughy things and a lot of us kids would eat under the tableâthere were no chairs for us.” Other foods stand out in her memory. “

Teglach

âthe honey things with nuts and fruitâoh, I loved those. Macaroons. My grandmother made a lot of knishes. And chicken, chicken, chicken.”

Sills, seventy-four when we met, stopped being a Silverman when she began her professional career at age seven. She debuted in a movie for Twentieth Century Fox, for which the producer, Walter Wanger, renamed her “Beverly Sills.” “They decided that Belle Miriam Silverman was the wrong name to put on a marquee,” she says. Her family, however, has never called her either Beverly or Belle. “My family has always called me âBubbles,'” she says. “My mother and brothers always call me âBubbly.'”

For someone called Bubbly, her life has been anything but. She married a man thirteen years her senior, Peter Buckley Greenough, who wasn't Jewish, which dismayed her mother and caused her relatives to boycott the wedding: “They didn't want to come,” she says. When I remark that that must have been hard, she shakes her head: “It was terrible, not just hard.

Terrible

.”

She started caring for Greenough's three children, one of whom was handicapped, and when she and Greenough had two children of their own, each was born with disabilitiesâa daughter, Meredith (“Muffy”), who was deaf, and a son, Peter Jr. (“Bucky”), so severely retarded that today he lives in an “adult village” for the handicapped.

Sills says religion didn't help her handle these trials. “I drew on my mother,” she says, and describes Mrs. Silverman in terms so over-the-top, they sound operatic. “My mother was one of the strongest, most intelligent, brilliant women I ever met. It's deceptive, because all my life, I've always called her âMama,' and people always had the impression she was one of these chubby little ladies, and then when they saw her, she was one of the most breathtakingly beautiful women I've ever laid eyes on. She wasn't just a pretty little hausfrau; she was breathtaking. I'm telling you, she would walk down the street and people turned to look. She was incredible. She was also, you know, one of those women who had dreams for her children and made them all happen.”

But it wasn't her dream for her daughter to marry out of the faith. Sills describes dropping the bomb when she told her mother about her new beau: “I said he was married, had three children, his divorce was going to take a little while, and he wasn't Jewish. And she burst into tears and said, quote, âWhy does everything happen to my baby?' So it was not well-received. My father was already deadâI think she was grateful that he was. And yet we both agreed that Peter was my father's kind of man.”

By that she means, Greenough was accomplished and impressiveâa successful newspaper owner in Cleveland. “And he was very difficult,” she adds; “I would not have liked to have worked for him. He was very arrogant. His saving grace to my mother was that he was very handsome. I mean, he was a knockout. When he walked into our one-bedroom apartment in Stuyvesant Town [in New York City], she said, âWell you're certainly handsome enough.' I guess she couldn't think of anything else to say that was nice. But what really impressed her was how well-educated he was: multilingual, sophisticated, flew his own plane, an officer in the air force, decorated. Very self-assuredâhe's thirteen years older than I, so my mother knew she couldn't push him around.”

I ask Sills how painful it was that her marriage hurt her mother. “I'm ashamed to tell you it wasn't,” she answers, “because I knew my mother was a powerhouse. I never worried about her.” Greenough also worked hard to win her mother over. “He was very clever because he didn't just court me; he courted my mother. He brought her books, and I remember a lovely little silver pen that was very ornate and Russian. And whenever he flew in to visit me in New York, he would take the two of us to dinner Friday. Mama used to love it: There was a restaurant, I think it was called Le Veau d'Or, and she just loved it when he ordered in French.

“You know, they never fully accepted one another,” Sills continues. “They had something in common and that was me. And my mother wanted nothing more than for me to be happy and that was what he wanted too, and so, with this common goal, they overcame all their prejudices.”

They were married in her singing teacher's studio by a justice of the peace. Peter's father refused to meet Sills until the wedding day. “Later I asked him,” Sills recalls, “âWhat was your reaction when Peter told you he was going to marry a Jewish opera singer?' He said, âWell, I was on my boat fishing and I had two choices: I could have thrown myself overboard or gone right on fishing, and being the intelligent man that I am, I went right on fishing.' We later became best friends. I could never have survived the many things that happened to meâto Peter and meâwithout the support of Peter's father.”

Sills and Greenough agreed to honor one of each other's holidays. “We made a deal at the beginning,” says Sills, “that he would do Passover and I would do Christmas.” Her brother ran the seders until he died. “He was the catalyst for bringing us all together and went through all the rituals. I see now that unless I do it, it's not going to happen.”

She describes her early years in her husband's Cleveland mansion like she was Little Orphan Annie moving into Daddy Warbucks's palace. “I'd never seen a house like thatânever mind living in one,” she says. “There were a lot of ladies running around keeping it clean and it was a culture shock. I'd left Stuyvesant Town, where my bed went into the closet during the day, into this incredibleâI mean, it was a chateau.” She never got comfortable with it. “If today someone said, âYou've got to go back to Cleveland and that house is waiting, I'd say, âFind me a nice condominium where I can call the super.'” The Cleveland social set didn't make things easier. “It was a totally non-Jewish five years,” she says. “Totally non-Jewish. And I found it quite anti-Semitic and not terribly friendly.”

How did that manifest itself? “Just remarks dropped in my home. A man who worked for my husband on the paper [the

Cleveland Plain Dealer

] in a quite high position, said to me after drinking a nice bit of very good wine, which I regret having served to him, âYou know, if Peter's mother were alive, she'd die all over again; if she knew he had married a Jew.' And I said, âDon't worry;

my

family went into mourning, too.'”

But when it came to her stage persona, her ethnicity was meaningless. “In the operatic world,” she says, “in the final analysis, in the first act of

Traviata

, when the chorus leaves you all alone, it really doesn't matter what you are.” That belly laugh again. “You're on your own and it's the loneliest moment of your life! Jew, gentile, white, black, purple, orange, it doesn't matter. Fortunately I was in a profession where no one ever said, âWe're not going to let her sing Violeta: she's a Jew.' The word âtalent' was the primary word. I was never referred to as âa talented Jew.' I was referred to as âa talented soprano.'”

Despite the fact that Sills's career defines her in the eyes of the world, it was not central to her husband, who became neither her manager nor her groupie. “I always tease that he thinks all operas end happily,” she says, “because he never stays till the end of them.” When she talks about her husband, it's with a distinct combination of reverence and candor. “I won't use the word âarrogance' [although she already did previously], but he has a self-assurance that makes him a little bit less than lovable to other people. And I know that he could antagonize people and he antagonized a lot of my friends who decided that either they loved me enough that they were going to put up with him and they did . . .”âthat sentence ends there. “Peter's a powerhouse,” she continues (a psychologist might note that she used the same adjective to describe her mother). “He's very sick now, but up until six years ago, when he was eighty, he was one of the most extraordinary men I've ever knownâone of the most difficult. I marvel at my strengthâI really doâin terms of maintaining my sense of self. Because he's overwhelming.”

He was also her stalwart supporter, encouraging her career despite keeping a distance from it. She says he made it possible for her to continue singing despite the many burdens at home. “It would not have happened without him,” she insists. “Because when I had this problem with both our children, he gave me fifty-two round-trip tickets from Boston [they were living in Milton, Massachusetts, when the children were young] to go into New York every week, take a singing lesson, visit my mother, have lunch with a friend, and come back in time for a late dinner with him. That's the way he did things.”

She refers to her children's disabilities as a “horror”: “I had stopped singing when all this horror happened, and he thought I should go back to singing for therapy. He thought it was a lot better than sitting in some doctor's office bemoaning my fate.”

Her children's health issues made any question of a Jewish upbringing moot. “I probably would have been much more aggressive about it,” she says, “had my daughter not been born with such problems.” She even had to swallow hard and put her daughter in a convent school in Boston because it was the best facility for the deaf at that time. Even her mother was in favor of it. “There was my mother saying, âIt doesn't matter; we've got to get Muffy using a hearing aid and you've got to get this child

educated,

educated

.' It's

all

she talked about. We were ten minutes away from the Boston School for the Deaf, which is run by the Sisters of Saint Joseph, who are probably the finest teachers of deaf children in the world. Even my mother didn't hesitate one bit. So my daughter, for the first seven or eight years of her life, was a

Catholic

.” Sills seems to marvel at this even now. “She went through all the rituals along with the other students.”