Resurrecting Pompeii (38 page)

Read Resurrecting Pompeii Online

Authors: Estelle Lazer

Mounting evidence challenges the concept of ‘racial’ classification from skeletal remains and few scholars today would consider that there was any value in attempting to identify European ‘races’, as these almost certainly do not exist (Chapter 3). Nonetheless, there is still some information that can be gleaned about population affiliations from human skeletal remains.

It was generally assumed that the Pompeian population was heterogeneous, since the town was a river port with a long history. As discussed in Chapter 4, literary evidence has been invoked to support this notion, like Strabo’s description of the different groups that occupied Pompeii over time. Similarly, Pliny the Elder stated that Campania had been inhabited by Oscans, Greeks, Umbrians, Etruscans and Campanians.

1

The composition of the population would also have been affected by the colony of veteran Roman soldiers that was superimposed onto the population by Sulla as punishment for resisting Rome in the Italic War.

2

An explanation would have to be sought if the population were found to demonstrate some degree of homogeneity.

Various factors may have had an impact on the composition of the

AD

79 population, including partial abandonment of the settlement as a result of the

AD

62 earthquake and subsequent seismic activity in the final 17 years of occupation. It is possible that the sample of victims may not reflect the

AD

79 population, depending on the time of the year of the eruption and whether it was possible for certain sections of the community to have more opportunity to escape prior to the lethal phase. The most recent evidence casts more than doubt on the generally accepted August date, which means that seasonal inhabitants would have returned to Rome after the summer (Chapter 4). The issue of Pompeian heterogeneity was examined by the collection of both metric and non-metric data, which were subjected to metric and non-metric analysis. While the contribution of DNA studies cannot be ruled out in the future, current research on the populations of the victims of the

AD

79 eruption relies only on macroscopic analysis.

Molecular biology has the potential to provide valuable insights into the population affinities of the victims of the

AD

79 eruption. DNA analysis has been attempted on samples from both Pompeii and Herculaneum, but the results to date have been disappointing. The high temperatures to which the bodies were exposed at the time of death have been invoked to explain the poor preservation of nucleic acids in samples from the Herculaneum skeletons. Human skeletal remains from Pompeii have also yielded limited information due to poor DNA preservation. Nonetheless, these preliminary studies indicate that, at least in some cases, there is sufficient endogenous DNA to enable amplification and analysis.

3

The main material used for this research was the cranial collection stored in the Forum Baths, as it appeared to reflect a random sample of adults that tended to be more complete than the skulls housed in the Sarno Baths (Chapter 5). Population studies are usually confined to adult material as the results obtained from skulls where growth is not yet complete would be misleading.

Population studies have traditionally been based on measurements of skulls (Chapter 3). It was appropriate to commence the study of the Pompeian sample in a similar fashion as the data collected could be compared with those published in the earlier work of Nicolucci well as Bisel’s measurements of the Herculaneum sample. Unfortunately, D’Amore

et al

. did not publish their raw data. Capasso only took minimal cranial measurements, enabling him to calculate a series of indices, which he considered to be most useful descriptors of the Herculaneum heads. Astonishingly, these included the now largely abandoned horizontal or cephalic index (Chapter 3). While he did present the indices for the sample, he did not include the raw data.

4

Bisel restricted her study to adult male skulls

5

and made 11 measurements on 50 skulls. These were compared with an early study of Howells, which was used to develop standards based on Irish monastery burials. Bisel calculated the cumulative standard deviation for her sample and found it to be greater than the norm for the Howells data. Bisel suggested that the considerable variability of the cranial metric data from the Herculaneum sample was a reflection of a heterogeneous population with the implied benefits of hybrid vigour which would have been ‘manifested in great energy and creativity’. While a large standard deviation does imply variability, recent work suggests that an isolated sample can also exhibit considerable variation. Howells, for example, demonstrated this in his later studies using Berg data, which represents a population that was geographically isolated over a number of generations.

6

It is apparent that the standard deviation alone does not provide information about the composition of a population.

The fact that many of the Pompeian skulls were incomplete hampered the collection of cranial metric data. A series of 12 measurements were made on 117 adult male and female skulls. The analysis of these data was compared with similar analyses based on the raw craniometric data published by Nicolucci in 1882 to establish whether there was consistency between samples. The 12 cranial measurements were then compared with data collected by Howells from a variety of European and African populations, the Pompeian skeletal sample studied by Nicolucci and the data collected from the Herculaneum material by Bisel to gain some understanding of the Pompeian sample in relation to other populations.

7

Metric evidence from the skull sample provided insuf ficient evidence to establish whether the Pompeian and Herculaneum samples reflect homogeneous or heterogeneous populations. Comparison with other samples from European and African contexts tended to confirm the European affinities of the sample. As expected, the data from the current Pompeian sample was closest to Nicolucci’s earlier sample and Bisel’s Herculaneum sample, though there were exceptions for some measurements.

It should be noted that a large proportion of the observed craniometric differences in the Pompeian sample appear to be intrapopulational rather than interpopulational and probably reflect variation between male and female skulls. Even though differences could be observed between the sexes in the Pompeian sample, the results of my study indicate that the skull, and the craniometric data in particular, do not provide a very useful sex indicator for the Pompeian skeletons (Chapter 6). By implication, these cranial measurements are of limited value for the determination of population affinities for this sample as they did not indicate any real separation into well-defined groups.

Non-metric traits are anomalous skeletal variants, which are generally nonpathological. On the whole, these present as innocuous features on the bone. It is unlikely that individuals would ever notice that they had such traits. They are mostly of interest to physical anthropologists as they are easily observed and counted. They are also known as epigenetic traits and occur with varying frequency in all populations. A study of the pattern of cranial and post cranial anomalies can provide information about population variability.

Because skeletal inheritance is multifactorial, the genetic and environmental components of non-metric traits cannot easily be distinguished. Human and mouse pedigree studies have established a genetic component for a number of traits, though a genetic basis is not essential for a non-metric trait to be a useful population descriptor. The acquisition of traits as a result of shared environmental factors, especially during the period of growth and development, can also reveal information about a population. The potential of epigenetic traits as population descriptors is supported by the consistency of the results from a large scale study of non-metric cranial traits for a number of populations with genetic and other morphological studies that have been made to establish population distance.

8

It should be borne in mind that there is no reason to assume regional immutability over time, especially for traits that have an environmental component.

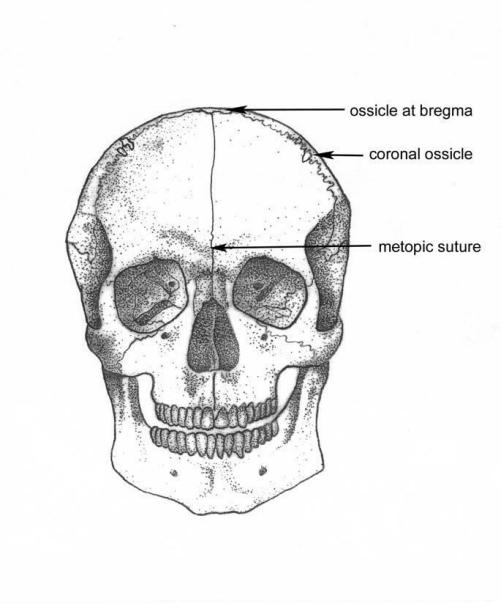

Figure 9.1

Facial view of skull, showing some of the non-metric traits that were observed in the Pompeian skeletal sample (adapted from Comas, 1960, in Krogman, 1962, 316, and Brothwell, 1981, 94)

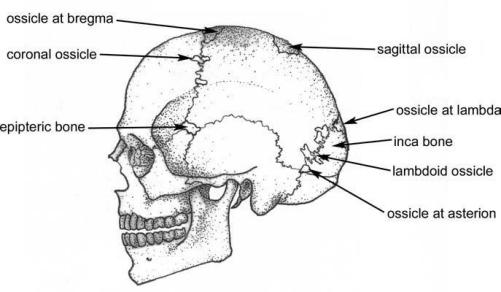

Figure 9.2

Lateral view of skull showing some of the non-metric traits observed in the Pompeian skeletal sample (adapted from Comas, in Krogman, 1962, 317, Brothwell, 1981, 94)

Twenty-eight cranial non-metric traits were scored on 126 skulls in the Forum Bath collection.

9

Standard definitions for scoring traits were provided by Hauser and De Stefano.

10

Because of the comparatively low retention of maxillae and mandibles, and the high rate of post-mortem tooth loss as a result of poor storage techniques, only one dental non-metric trait was scored. This was the presence or absence of double-rooted canines.

Intra and interobserver variation in scoring traits has been well documented.

11

Interobserver error was not an issue for this study as I was the sole person scoring the Pompeian skeletal sample. Intraobserver error was addressed by rescoring traits on the same bones over a period of years without reference to previous studies. An extremely high degree of concordance was found between scores taken at different times over a five-year period.

Where possible, comparison was made with the results from observations made by other scholars who have worked on the

AD

79 victims. The only available published material was produced by Nicolucci and Capasso.

12

Nicolucci scored the traits he observed from his sample of 100 skulls. It is difficult to establish the exact sample size that Capasso employed for the non-metric traits that he scored. He claimed to have based his study on the adult sub-sample of the Herculaneum skeletal collection that was available to him but, when the percentages he presents are scrutinized, it is apparent that his sample was 159, which meant that he also included sub-adult material.

13

It is notable that Capasso used the same standard scoring scheme that was used for the Pompeian study.

14

The practice of cremation as the primary method of disposal of the dead in the Roman world in the first century

AD

is an impediment to obtaining appropriate comparative material. As a result, a number of the other skeletal samples used for comparison with the Pompeian material were temporally and geographically different. The cranial non-metric data collected from the excavations at the medieval monastery at San Vincenzo at Volturno provided comparative material from another Central Southern Italian site. Two groups of skeletons were unearthed at this site: the first were from the late Roman period and the second from the early medieval period. These two groups of skeletons have been interpreted as 84 workers from a large villa estate of the fifth century

AD

and 69 lay workers from the monastery. The latter set of burials comprised individuals from family groups of tenants who worked the monastic land. The monastery was in use from the eighth to the end of the ninth century

AD

.

15

Further comparative Italian material was obtained from a study of frequencies of nine non-metric traits for ten skeletal series from central Italy that dated from the ninth to the fifth centuries

BC

. Two of these series were from Campania; one from Sala Consilina, dating between the ninth and the sixth centuries

BC

and one from Pontecagnano, dating between the seventh and sixth centuries

BC

.

16

Other Italian samples included: a presumably homogeneous Iron Age sample from Alfedena in the Abruzzo, which dated from 500–400

BC

, an early twentieth-century collection from the University ‘La Sapienza’ in Rome, a cranial sample from East Sicily, dating from the second and first millennia

BC

, a number of Iron Age skeletal samples, dating from the first millennium

BC

, from either side of the Apennine mountains, including three samples from the area to the south of Naples, a Sardinian sample of adult males and an Etruscan population from Tarquinia.

17