Resurrecting Pompeii (35 page)

Read Resurrecting Pompeii Online

Authors: Estelle Lazer

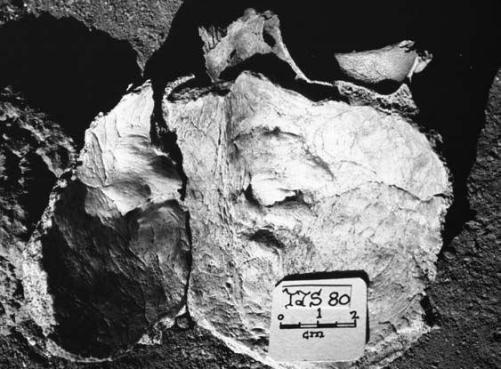

Figure 8.9

Figure 8.9An apparent case of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) observed on thoracic vertebrae associated with TdS NS: 1

right anterolateral aspect of all the affected vertebrae. The appearance of the pathology was far more consistent with a diagnosis of DISH than any other disorder of the vertebrae, such as the autoimmune joint disease, ankylosing spondylitis. The latter case was one of at least four individuals that were excavated in 1986 and were stored in the same box. The other bones that could be associated with this person were the skull and mandible, a left femur and the pelvis.

129

Osteophytic change

130

was apparent on the articular surfaces of all the bones that could be associated with these vertebrae. The skeleton presented as slightly mid-range but female. The skeletal age indicators, based on the pelvis, skull and teeth, were consistent with an older adult, at least in the fifth or sixth decade.

With the exception of the two cases of DISH, it is dif ficult to assess the osteophytic change observed in this sample. Some of the cases probably do reflect age-related osteoarthritis, though consideration must also be given to the possibility that some result from trauma (see above) or occupational stress. It has been suggested that there is a tendency for individuals to develop premature degenerative joint disease in complex communities which feature specialization in craft and trade as a result of excessive strain from intensive and repetitive activities.

131

Whatever the cause, pain and lack of mobility associated with osteophytic changes might well have slowed down or discouraged individuals from making good their escape from the eruption. It is notable, however, that the incidence of eburnation

132

in long bones is not particularly high, with an overall frequency of 3.4 per cent in the Forum Bath femora collection (3.1 per cent in the left and 3.8 per cent in the right femoral sample) and 8 per cent in left humeri.

The presence of DISH is merely indicative that there were individuals who survived into older adulthood. It has been asserted that DISH is not a disease but a reflection of the ageing process. It is not considered to be a true arthropathy because it does not involve the cartilage or the synovium. It appears to result more from excessive bone production at joint margins. Despite its appearance, it is not particularly debilitating. This is because it tends to involve the thoracic vertebrae. This means that anterior flexion, which mostly involves the lumbar segment, is largely unaffected. In addition, the disc spaces and the facet joints present as normal. It is hard to correlate the decision to remain in Pompeii during the eruption with the presence of an age-related disorder, like DISH. While afflicted individuals would hardly have been advantaged, escape would have still have been possible. The presence of osteophytic change in the Pompeian sample is low and cannot be used to support the notion that only people with infirmities were unable to escape the eruption.

133

Bisel recorded a slight to moderate degree of vertebral arthritis in 47.5 per cent of the males in the Herculaneum sample and 36.4 per cent of the females. She explained the sex difference in frequency to be the result of males having engaged in heavier work than females, though no evidence was presented to substantiate this claim. She compared the combined frequency of 42.5 per cent for vertebral arthritis in the sample with a rate of 67 per cent in that recorded for a modern American sample. She explained the disparity as the result of the American sample being composed of older individuals. She concluded that the American data reflect degenerative disease due to age rather than stress, which she invoked as the most likely cause for vertebral changes in the Herculaneum victims. The diagnosis of a case of DISH in her sample is consistent with this interpretation.

134

Capasso also reported high rates of osteophytic change to the vertebral columns of the victims in his sample. He diagnosed five cases of DISH, all in male skeletons, though it should be noted that Becker questioned the accuracy of the diagnosis of this disorder in all these cases. Osteophytic changes were recorded at articular surfaces of bones in 69 of the victims and he noted that these changes were more prevalent in males than females at all locations with the exception of the region around the knee, where they were equivalent.

135

The discovery of bilaterally symmetrical deposits of bone overgrowth on the inner table of the frontal bone of a skull in the Pompeian sample led to the investigation of the available crania for evidence of hyperostotic change. Complete crania were examined through the foramen magnum with the aid of a torch and direct observations were made of the surfaces of incomplete specimens in the sample of 360 skulls that were well enough preserved to enable observations to be made. Forty-three skulls were identified as having some degree of hyperostotic change.

136

These bony growths have been diagnosed as hyperostosis frontalis interna (HFI), a disorder generally associated with post-menopausal women that has arguably been described as a syndrome with a suite of signs and symptoms, including obesity, hirsutism, non-insulin dependent diabetes and headaches. HFI can be diagnosed from the skull alone, which means that the disarticulated nature of the sample does not have a significant effect on the confidence of diagnosis.

Classi fication of the degree of bony involvement was largely based on the system proposed by Henschen.

137

This system is roughly equivalent to the one more recently proposed by Hershkovitz

et al

.,

138

which is also based on the degree of tumour development and the area of bone involvement.

The features observed on 40 of the 43 crania in this sample concur in all respects with the descriptions of hyperostosis frontalis interna in the literature.

139

The majority of cases that were identified as having bony changes consistent with HFI displayed only very slight deposits of additional bone on the inner table of the frontal bone. Seven cases were described as slight, five as moderate (Figure 8.10), and one skull exhibited pronounced bony changes (Figure 8.11). There was only one skull in this series, which demonstrated extensive bony tumorous swellings (Figure 8.12).

140

The three most

Figure 8.10

Figure 8.10Inner table of the frontal bone of a skull (TdS 80) displaying moderate hyperostosis frontalis interna (HFI)

Figure 8.11

Figure 8.11Inner table of the frontal bone of a skull (TdS 28) displaying pronounced hyperostosis frontalis interna (HFI)

Figure 8.12

Figure 8.12View through the foramen magnum of a skull (TF SND) displaying extensive hyperostosis frontalis interna (HFI)

equivocal cases were not included with the diagnosed cases of HFI. The bony growths associated with these cases tended to be rather asymmetrical, though it has been suggested that HFI can present as asymmetrical in the early stages of development.

141

Also, some of the cases may have appeared asymmetrical because the skulls were incomplete. When it has been possible to reconstruct skulls with this disorder from fragments found in the Sarno Bath collection, the expression does appear both greater and more symmetrical.

Hyperostosis frontalis interna is anatomically characterized by the occurrence of bilaterally symmetrical, benign bony tumours and marked thickening on the internal surface of the frontal bone. The midline is generally spared, which gives it a ‘butterfly-like’ appearance. When viewed in crosssection, the new bone is mostly revealed to be cancellous and integrated with the diploë, or spongy tissue between the inner and outer tables of the cranial bones. Diagnosis of this disorder is based on the existence of such growths, irrespective of their degree of expression. HFI has been classified by some scholars as a symptom of various syndromes but current wisdom is that it is a distinct pathological entity. It has been described as the most obvious skeletal indicator of an endocrine disorder of uncertain aetiology, or origin, and there has been considerable discussion about its clinical manifestations. It has been suggested that HFI is associated with hyperlactinaemia. This results in an increase of adrenal androgen production, carbohydrate tolerance and hypothalamic hormone secretions, all of which would contribute to the occurrence of obesity, hirsutism and diabetes. Other suggested contributors to the development of HFI include estrogens, dietary phytoestrogens, parathyroid hormone, calcium modulating agents and neuropeptides.

142

Based on unselected samples in hospitals, the frequency of hyperostosis frontalis interna in modern European populations is generally thought to vary between 5 per cent and 12 per cent, though some scholars suggest the incidence might be as high as 15 per cent.

143

The frequency of HFI in the Pompeii sample, at between 11.1 per cent and 11.9 per cent, is consistent with this range.

Surveys of the incidence of HFI in modern Western populations indicate that HFI is most commonly associated with females.

144

It has been, perhaps rather extravagantly, suggested that the correlation between the occurrence of HFI and women is so high that its presence alone should be sufficient as a basis for sex attribution from archaeological skeletal material.

145

It is most frequently observed on post-menopausal women, with a reported incidence of 40–62 per cent amongst this group in modern populations, and has been associated with adiposity and male-type hair growth patterns, though the three features do not always occur together. Various other signs and symptoms can accompany HFI, the most common being headaches. HFI-associated headaches apparently are hormonally induced and not related to excess bony development. The degree of bony change to the inner table of the frontal bone does not necessarily reflect the degree of development of other signs and symptoms, though it has been suggested that the severity, like the frequency, appears to be age dependent.

146

Nonetheless, it probably would not be reasonable to draw specific conclusions for the variation in expression observed in the Pompeian sample.

There is some suggestion that there may be a genetic component in the manifestation of this disorder. It has been detected in four generations of one family, and in individuals from archaeological contexts who possibly were related but, as yet, there have been no definitive inheritance studies.

147

The Pompeian skulls diagnosed with HFI were examined to determine whether the presence of this syndrome had any bearing on the survival prospects of affected individuals in the

AD

79 eruption or whether these cases just reflect the normal incidence of HFI in the ancient Pompeian community.

Since HFI is both sex and age-related, it was necessary to establish both for the sample, but there can only be limited confidence in sex and age-at-death attributions based solely on skulls, especially ones that are not well preserved.

The majority of the skulls

148

exhibited more female than male characteristics, which is consistent with the greater female prevalence of this disorder that has been observed in modern populations. One skull was completely mid-range, five skulls appeared to be more male than female and one skull presented as male. Another skull was so incomplete that no diagnostic features were retained and no sex attribution could be made.

149

It is possible that some of the six skulls, which display predominantly masculine traits, may be female. Virilism, in the form of the development of masculine facial features, has been associated with HFI and such changes could be detectable on the skull. In addition, it is not uncommon for the skulls of normal older females to develop male traits.

150

It should also be reiterated that the confidence levels for sex determination solely from skulls in the general Pompeian sample were not very high (see Chapter 6).

Though the skulls were generally too incomplete to enable a full set of observations to be made, it was still possible to see general trends in terms of relative age-at-death. The majority

151

could be identified as adult, with most of the individuals tending towards older ages. Two skulls lacked sufficient diagnostic features to establish age-at-death but did not appear to be juvenile. Six skulls could be identified with certainty as adult but they were too incomplete to enable further assessment. Seven skulls presented as consistent with an age estimation of, at least, the third decade, ten the fourth decade or older, the minimum ages of a further 14 were consistent with the fifth decade and four individuals with, at minimum, the sixth decade.

152

It must be remembered that the ages attributed to nearly all of these cases reflect minimum ages-at-death as it was not possible to build up a complete score due to the poor preservation of the skeletal remains. It is therefore likely that most of the individuals in this sample were chronologically older than their estimated ages. Further, age-at-death attributions are notoriously unreliable for adult skeletons, especially when based solely on features of the skull. At best, the age markers that were employed could be used to seriate the sample. The results certainly demonstrate skewing towards the older age range, which would be expected for a sample of individuals with hyperostosis frontalis interna.

As for sex, the correlation between maturity and HFI is so high that it has been suggested that adult age can be reliably estimated for archaeological skulls that display some degree of HFI.

153

With some qualifications, the results obtained from the Pompeian sample for sex and age are consistent with a diagnosis of HFI.

Differential diagnoses have been considered for the archaeological cases of bony lesions that have been interpreted as hyperostosis frontalis interna.

154

The features that have been described for at least 40 of the cases of hyperostosis in the Pompeian sample are characteristic of HFI with clear boundaries, which limit overgrowth to the inner table of the frontal bone, an unaffected midline and overall bilateral symmetry. Other disorders that are associated with additional cranial bony growth, such as Paget’s disease, senile hyperostoses, Leontiasis ossea and acromegaly, are easily distinguished from HFI as they do not tend to be confined to the frontal bone and they involve both tables. Leontiasis ossea is further excluded as a possible interpretation because it results in the destruction of the frontal sinuses. In all the cases in the Pompeian sample where the bone was complete enough to assess, the frontal sinuses appeared normal.

The lesions observed in the Pompeian sample, including the more equivocal cases, are too large to be diagnosed as pregnancy osteophytes. These appear as a thin chalky layer of surface parallel periosteal bone, most commonly on the outer table, though those that are observed on the endocranial surface are usually found in the frontal region. The growths are usually less than 0.5 mm in thickness. These changes, along with an increase in the weight and density of the cranial vault during pregnancy, have been attributed to changes in pituitary hormone secretion.

Caffey ’s disease, or infantile cortical hyperostosis, could not be considered a reasonable alternative diagnosis as it only occurs in young children. It affects the skeleton of infants in the first year of life and is characterized by a large deposit of layered periosteal woven bone on one or more bones. The bones that are most frequently involved are the mandible and the clavicle. The skull generally suffers no bony change.

Fibrous dysplasia is not implicated as an alternative diagnosis because it presents quite differently to the observed hyperostotic changes in the Pompeian cranial series. The cause of fibrous dysplasia is not understood. It can occur in single or multiple bones and is often confined to one limb or one side of the body. It is more commonly found in females and is manifested as faulty differentiation of the parts of the osteogenic mesenchyme into fibro-osseous tissue. The lesions associated with this are characterized by fine trabeculae of woven bone.

Another unlikely alternative diagnosis is other types of neoplasm or tumour. These tend to be more destructive than HFI and usually involve both tables.

Though it appears likely that the diagnosis of HFI is the most reasonable option, it is important to note that as the sample was disarticulated, it was impossible to assess the Pompeian sample for post-cranial pathological involvement. No clear alternative diagnosis is apparent for the three cases that were marked by some degree of asymmetry and tubercules.

All bony changes to the skulls that could be attributed to a pathological cause were recorded, both to confirm that the diagnosis was correct and to establish whether there was any linkage between HFI and additional pathology that was present on these skulls. The range of observed pathology included porotic hyperostosis, ante mortem tooth loss, dental abscess, interdental alveolar resorption, button osteoma, osteophytic change and trauma.

No well-developed cases of porotic hyperostosis were observed in this sample and those cases only presented as cribra orbitalia (see above). Of the 37 skulls that were sufficiently preserved to enable observations to be made, 32 exhibited minimal to slight pitting, with only one case demonstrating a medium degree of expression. Four skulls did not display any sign of cribra orbitalia. The incidence and degree of expression observed on the skulls diagnosed with cribra orbitalia was consistent with that observed in the overall skeletal collection and does not appear to have any particular relationship to the presence of HFI in the sample.

Since the causes of various dental problems are related, it is appropriate to consider dental pathology as a whole. Some degree of pathology was observed on the majority of the surviving maxillae, though only eight cases were sufficiently preserved to enable dental observations to be made. Post mortem tooth loss prevented the assessment of caries or enamel hypoplasia in this sample. Slight alveolar resorption was observed on the maxillae of six individuals, one displayed medium resorption and no sign of resorption was visible on the remaining maxilla. Six of the eight maxillae displayed evidence of loss of between one and five teeth some time prior to death. Abscesses were recorded in the maxillae of five of the eight cases where observations could be made. Evidence of one abscess was observed in four cases and three abscesses were evident in one case.

Dental pathology in these cases could have resulted from various causes. It is worth considering, however, that such dental problems can be exacerbated by age-related changes to teeth, such as attrition, and in most populations occur with increasing frequency as an individual ages.

155

It is impossible to draw conclusions from such a small amount of material, beyond the inference that the presence of such pathology may suggest older individuals, which, in turn, would be consistent with the identification of HFI.

Two cases of button osteoma were observed in this sample. These usually occur on the outer table of the cranial vault and present as a smooth lump of compact bone with a maximum diameter of two centimetres. The occurrence of these benign tumours is independent of HFI. They were probably asymptomatic and had no impact on the individuals who had them.

156

Osteophytic changes to the articular surface of the temporal part of the temporo-mandibular joint were discerned on four of the seven skulls that were sufficiently preserved to enable assessment. It would be impossible to attribute a specific cause for these changes, though they could be associated with increasing age, some degree of malocclusion or tooth loss. The possibility that these changes might be age-related is also consistent with HFI.

Evidence of trauma was only observed on one skull. This pathology had features consistent with changes that can be observed on healing trephinations (see above). Trephination, a surgical procedure involving the removal of a portion of the cranial vault, was performed for a number of reasons in antiquity, including the excision of splinters from fractured skulls, alleviation of the symptoms of epilepsy and the treatment of headaches.

157

There is no apparent reason for the performance of this operation, though the presence of hyperostotic changes may be invoked to postulate that the trephination might have been undertaken to relieve headaches that have been associated with HFI. If this were the case, the operation, though successful in that there was healing well with no sign of secondary infection, would not have been of assistance, as such headaches would have a hormonal origin.

To summarize, all the pathological changes observed on these skulls could be interpreted as either consistent with HFI or as independent entities. No pathology that conflicted with the diagnosis of HFI was identified in the forty crania that were unequivocally diagnosed.