Red Capitalism (25 page)

Authors: Carl Walter,Fraser Howie

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Finance, #General

PBOC and CBRC surveys found such local platforms had borrowed some RMB6 trillion (US$880 billion) by the end of September 2009, with nearly 90 percent of stimulus projects tied to bank loans.

9

These same surveys also noted that these loans amounted to 240 percent of local government revenues and, in 13 of China’s 29 provinces and autonomous zones, liabilities exceeded total fiscal revenues. These local borrowings were found by the CBRC to account for 14 percent of total lending in 2009 and, for some banks, as much as 40 percent of total new credit issued. By year-end 2009, Beijing was publicly admitting to RMB7.8 trillion (US$1.14 trillion) in outstanding local-government bank debt.

If this widely reported figure is accurate, then local governments and their agencies have borrowed the equivalent of 23 percent of the country’s annual GDP. Analysts at China International Capital Corporation (CICC) put current debt levels at RMB7.2 trillion (US$1.1 trillion), peaking at RMB9.8 trillion (US$1.4 trillion) in 2011. But the report provides an even greater service when it states: “If the financing chain for the platforms is not broken, they will be able to dissolve potential credit risks in the course of current economic development trends.”

10

In other words, as long as banks continue to lend, there will be no repayment problems. As will be discussed in this book’s conclusion, rolling outstanding debt when it matures—that is, re-issuing new debt to repay the old—is a principal characteristic of China’s financial system.

Provincial government semi-sovereign debt

As noted earlier, in March 2009, the MOF announced the issue of RMB200 billion (US$30 billion) of local-government bonds. These were rolled out rapidly, before a regulatory framework could be developed or the philosophy behind their credit ratings could be thought out. The thinking behind this seemed to be that as provincial governments are equivalent to ministries in the Chinese bureaucratic hierarchy, and thus represent the state, they would attract similar ratings. But most people know full well that Qinghai is different from Shanghai.

However, a spokesman for the MOF explained that although the debt would be issued in the name of the provincial governments and approved as a part of their budgets, the MOF would act as their agent. More importantly, given this, the coupon on, and the risk of, the bonds would approach that of sovereign debt. In essence, the spokesman was attempting to sell the idea that provincial issues carried risk equivalent to the country itself. While this may be true in theory, in practice, it is not and many market participants did not accept the idea. Moreover, this was not the picture presented in the MOF’s own rules governing local debt issues. These stated explicitly that if the locality could not make repayment, the debt would be rolled forward over a period of one to five years, with the original principal amount being repaid in installments the local government could afford. In short, the original three-year bond might, in fact, have a tenor of eight years or longer.

Clearly, this was not central government debt. Despite widespread questioning in the market, the bonds were priced closely to MOF bonds of a similar maturity by the friendly primary-dealer syndicate. What might have happened to prices in the secondary market is unknown because there has been no secondary market. The fact is, these bonds have disappeared onto the balance sheets of the MOF’s primary-dealer group, that is, China’s banks.

CHINA INVESTMENT CORPORATION: LYNCHPIN OF CHINA’S FINANCIAL SYSTEM

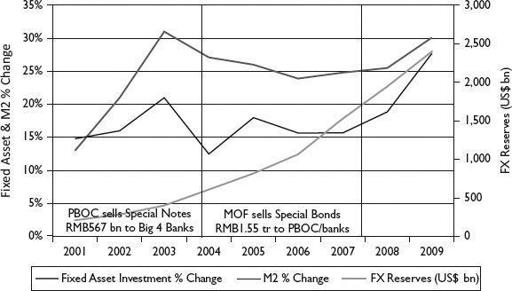

If the inter-bank market somewhat resembles a pyramid scheme, it nonetheless plays an extremely important role in the PBOC’s effort to manage inflation through control of the money supply. In 2002, a policy disagreement blew up over how to cool inflation that was threatening at that point. This disagreement evolved over four years into a struggle over how to manage the inflationary impulse caused by China’s huge trade surpluses. Driven by enthusiasm over China’s joining the WTO, fixed-asset investment exploded from 2002, increasing on an annual basis by 31 percent, the highest level seen since Zhu Rongji’s heyday began in 1993 (see

Figure 5.6

). Memories of mid-1990s double-digit inflation caused the PBOC to issue short-term notes continuously into the market for the first time in China’s post-1949 banking history. From an initial issue equivalent to US$26 billion in 2002, this rose over the following years until 2007, when the PBOC soaked up nearly US$600 billion from the banks. The central bank also adjusted upward bank-deposit reserve ratios nine times and raised interest rates five times. These aggressive measures were effective temporarily, but by 2007, the explosion in foreign reserves and the consequent creation of new renminbi posed an almost insurmountable challenge.

FIGURE 5.6

Investment, FX reserves and money supply, FY2001–2008

Source: PBOC, Financial Stability Report, various

Others also remembered 1993 and how Zhu Rongji had aggressively intervened in the economy using administrative orders to close off all channels to liquidity. Zhu simply shut off all bank lending, closing down the economy for almost three years until inflation that had peaked at over 20 percent in 1995 was finally beaten. The group favoring administrative intervention in 2002 argued that the economy was not overheating, only specific industrial sectors were and this could be dealt with using specific policy means. Their argument carried the day and bank credit to those sectors was cut off. By 2004, both efforts had reduced the growth of investment and M2 just in time to begin dealing with the flood of US dollars pouring into the country from China’s booming trade surplus.

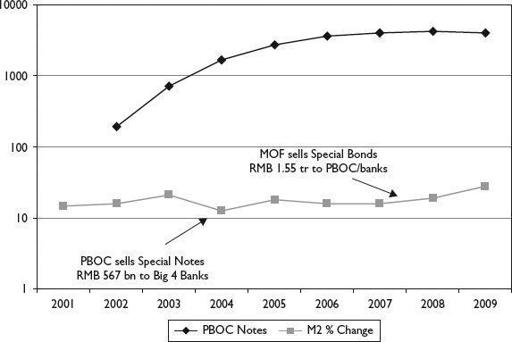

It was at this point in July 2005 that the PBOC succeeded in convincing the government to delink the RMB exchange rate from the US dollar and allow it to gradually appreciate. It was unfortunate that the predictability of the RMB’s 20 percent appreciation led to huge inflows of hot money and even greater liquidity in the domestic markets, not to mention an explosion in the stock index and high-end real-estate speculation. That both sides could claim success in this earlier anti-inflation campaign complicated things significantly later on after the outbreak of the global financial crisis in September 2008, when market forces fell dramatically from political favor. Despite the PBOC’s aggressive efforts to manage this flood of RMB, the data in

Figure 5.7

suggest that the effectiveness of short-term notes began to decline after 2007. The growth in the money supply as measured by M2 had been stable at 16 percent, but it accelerated to 19 percent in 2008 and then 29 percent in 2009. For its part, the policy of appreciating the currency was canceled as soon as export growth turned negative in late 2008.

FIGURE 5.7

PBOC note issuance vs. growth in money supply (M2), 2001–2009

Source: PBOC Financial Stability Report, various; China Bond

This is the macro economic background to the political struggle over China’s financial framework that had been continuing since 2003. The struggle came to center on the establishment in 2007 of China Investment Corporation (CIC). It is ironic to consider that this sovereign-wealth fund, established to invest the country’s FX reserves overseas, was in fact used to dramatically restructure China’s own financial system. CIC is not the country’s first sovereign-wealth fund. SAFE Investment Co. Ltd., a Hong Kong subsidiary of the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE), has been actively managing a portion of China’s foreign-exchange reserves since 1997. So why establish a second fund? SAFE Investment is owned by the PBOC; CIC is owned by the MOF. Why would the MOF want to encroach on foreign exchange, which has clearly always been the legitimate turf of the PBOC? The answer seems to be that since the PBOC took over outright control of two of the four major state banks from the MOF, the MOF had the right to seek their recovery. In the end, the establishment of CIC is less about a sovereign-wealth fund than a battle over bureaucratic territory. The outcome of this particular round, moreover, is very clear: CIC is now the very lynchpin of the country’s domestic financial system.

RMB sterilization and CIC

The story of CIC’s capitalization shows that all institutional arrangements in China are impermanent; everything can be changed as a result of circumstances and the balance of political power. All institutions are in play, even the oldest and most important. The case of CIC also shows the extent to which China’s financial markets have been distorted by the pressures created by the country’s tremendous foreign-reserve imbalance. This distortion now extends beyond the domestic capital markets, both debt and equity, to the financial institutions that provide their foundation and beyond to the international equity markets and investors.

Since it was designed to invest reserves offshore, it might have been expected that CIC would receive its capital directly from foreign reserves, as had the state banks. China Construction Bank, Bank of China, Industrial and Commercial Bank of China and Agricultural Bank of China had each been at least partially capitalized from the foreign reserves by way of a PBOC-established entity called Central SAFE Investment, known commonly as Huijin. In 2007, a surging money supply threatened a major asset bubble and the debate about how to handle this—whether through monetary tools or outright administrative measures—became mixed up with the MOF/PBOC rivalry. The MOF claimed that the PBOC’s management of reserves produced too low a return; from this it was a quick jump to the MOF asking for its own opportunity and then to a discussion of how to capitalize CIC. In the end, the Party agreed to allow the MOF a chance; after all, in 2007, there were plenty of reserves to be managed. But there was no direct infusion of capital into CIC as had been the case with the banks. Instead, there was yet another MOF Special Treasury Bond.

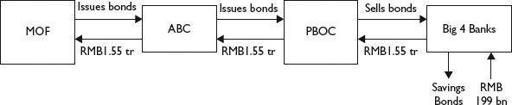

This Special Bond was approved by the State Council in early 2007 and its size was a mammoth RMB1.55 trillion (about US$200 billion with 10- and 15-year tenors), as shown in

Figure 5.8

. Not only had the MOF accused it of poor reserve management, the PBOC also stood blamed for monetary growth that threatened an outbreak of inflation. The path these bonds took tells the tale of the PBOC’s political weakness. The MOF sold the bonds to the PBOC in eight separate issues through the hands of Agricultural Bank of China. Direct dealings between the two had been prohibited by law since 1994 when the Central Bank Law was enacted; prior to this, the central bank had too often been forced to finance the state deficit directly. But this bond was not for deficit financing. The PBOC, for its part, bought the bonds from ABC and then, given their below-market interest coupons, forced them into the market, which consisted of the banks. This issue, therefore, drained a huge amount of liquidity from the banking system, an amount double what the PBOC had been able to achieve through its own short-term notes. This approach also relieved the PBOC of adding to a growing interest burden on its notes.

FIGURE 5.8

Step 1: MOF issues Special Bonds and drains market liquidity