Red Capitalism (21 page)

Authors: Carl Walter,Fraser Howie

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Finance, #General

Accessing funds from the banks had the effect of lowering the MOF’s interest expense. The Party could urge banks to buy bonds at levels just above the one-year rate they were paying retail depositors, while retail investors using the same bank deposits to buy bonds would require far higher returns. In other words, the banks provided the government with direct access to household deposits at government-imposed interest rates without even having to ask the depositor for permission: the banks simply disintermediated them. Unlike unruly retail investors seeking to maximize returns, banks had the pleasing aspect that their senior management (Party members) did as they were told. The Party was now easily able to direct funds where it wanted and in the amount it wanted without the need for excessive cajoling or paying market rates. Meanwhile, it could persuade itself that this was the right thing to do since it “protected” the household depositor from undue credit risk.

At first, there was no conflict of interest: individuals were crazy about shares, not bonds, and banks could not buy shares. But as China emerged from the major inflation of the mid-1990s, bonds suddenly offered a very attractive return in comparison to a collapsing stock index. The problem was that retail investors were unable to get their hands on them. In just a brief period of time, China’s banks had monopolized bond trading on the Shanghai exchange. The story goes that a feisty Shanghainese housewife complained about this

de facto

government-bond monopoly and her anger reached all the way to Zhu Rongji. Characteristically, Zhu took decisive action and in June 1997, he summarily kicked the banks and the bulk of government bond issuing and trading out of the exchanges and into what was then a small and inactive inter-bank market.

10

Since then, individual investors have been limited to buying savings bonds through the retail bank networks and institutional investors have been largely limited to the inter-bank markets.

11

This significant structural change meant that although the market continued to rely overwhelmingly on the state-owned banks, all other state-owned entities that could qualify as members could also participate (see

Table 4.5

).

TABLE 4.5

Number of investors, October 31, 2009

Source: China Bond

Note: Members include individual branches in the case of institutions.

| Member type | Number |

| Special members (PBOC, and other government agencies) | 16 |

| Commercial banks | 382 |

| Credit cooperatives | 830 |

| Non-bank financial institutions | 163 |

| Securities companies | 122 |

| Insurance organizations | 131 |

| Funds | 1,502 |

| Non-financial organizations | 5,908 |

| Total inter-bank market members | 9,054 |

| Individuals (not members of the inter-bank market) | 7,334,832 |

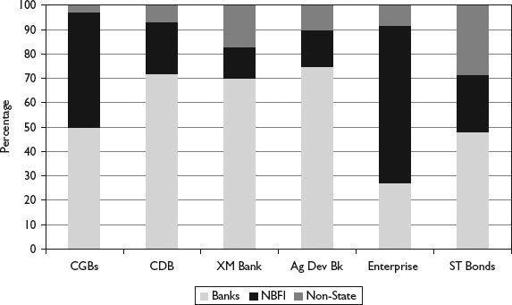

In short, bonds returned to their earliest stage, when the state was its own investor. But the principal difference was that banks and all other non-bank financial institutions replaced SOEs, which meant that household savings would be channeled directly by the Party. This explains how the banks came to hold over 70 percent of all fixed-income securities in China, including 50 percent of all CGBs, 70 percent of policy-bank bonds, and nearly 50 percent of commercial paper and medium-term notes issued (see

Figure 4.11

). Only in the case of the NDRC’s enterprise bonds do insurance companies (NBFI) displace the banks as the principal investors, holding some 46 percent of these securities.

FIGURE 4.11

Investor holdings of debt securities, by issuer, October 31, 2009

Source: China Bond

Note: Non-state investors include foreign banks, mutual funds, and individuals.

In the international markets, banks also dominate underwriting and trading, but investors and their beneficial owners are, of course, far more diverse, with large roles being played by mutual and pension funds as well as insurance companies. In China, such diversity is beside the point since all institutional investors, whether banks or non-banks, are controlled by the state. In such circumstances credit and market risk cannot be diversified. This is why China’s markets remain primitive and why there is the “implicit risk” alluded to by Zhou Xiaochuan.

In late 2009, the CBRC suddenly became aware of this inevitable reality when it stopped all issuance of bank-subordinated debt. Why had it been oblivious to this risk from the beginning? If the state owns China’s major banks outright, as it does, what is the significance of Bank of China issuing subordinated debt to investors that are largely other state banks? The state is simply fooling itself by subordinating its own capital to its own capital. The level of risk in the system has not changed one bit, even if the financial landscape seems the richer for adding this new product.

All of this raises the question of why it has been so difficult for foreign banks and other financial institutions to become involved in this market. Over the past 15 years, China’s leaders have witnessed the Mexican debt crisis of 1994, Argentina’s peso crisis of 1999 and the ongoing sovereign-debt crises of Greece and Spain. They have seen the huge ramp-up of their own stock index in 2007 and its collapse in 2008. Local newspapers and other media commentary are rife with talk of hedge funds, hot money and unscrupulous investment bankers. An inherently conservative political class, whose natural instinct is to control, will not easily invite those it cannot easily control to participate actively in its domestic debt markets. But, as appearances have to be preserved, there will always be slight movements toward market opening. But there will be no true opening.

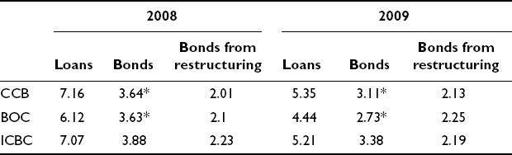

What would happen to bank and insurance company holdings of CGBs or other corporate and financial bonds in an inflationary environment? As mentioned, China’s central bank manages interest rates in order to contain change because change is risk. No matter that these state institutions hold fixed-income securities as long-term investments to avoid marking their value to market, in an inflationary environment their value will inevitably decrease as funding costs rise. The inevitable result would be a growing drag on bank income even if valuation reserves are not taken. This problem can be seen clearly in bank financial statements. For example, the auditors for ICBC’s 2009 financial statements usefully show separately the yields on the bank’s loan, investment-bond, and restructuring-bond portfolios (see

Table 4.6

).

TABLE 4.6

Yields on loans, investment and restructuring bonds, 2008–2009

Source: Bank FY2008 financial statements

Note: * CCB and BOC bond rates are calculated on portfolios that include the restructuring securities; hence returns are pulled down. ICBC rates have been separately calculated.

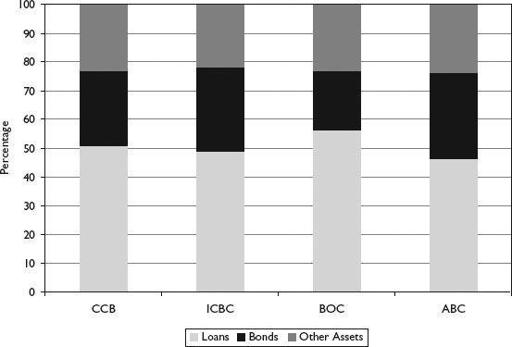

The restructuring bonds yield on average almost exactly the one-year bank-deposit rate and are fixed. In other words, in a low-inflation environment, they will nearly break even, whereas the bonds held as investments yield 3.34 percent, around 1.1 percent over the one-year deposit rate. This is somewhat better, but raises the question: why hold such huge bonds portfolios when loans yield on average nearly seven percent? Banks hold these portfolios partly for liquidity reasons, but largely because they are required to do so by the Party. If the ultimate objective of bank management were to maximize profit, would such low-yielding bonds make up 20–30 percent of their total assets (see

Figure 4.12

)?

FIGURE 4.12

Composition of total assets of Big 4 banks, FY2009

Source: Bank 2009 annual reports

Interest-rate risk holds true for all bonds, but corporate bonds also have a credit aspect. In the event of their inability to pay interest, banks will experience a drag on income and, sooner or later, would be compelled to re-categorize their internal credit ratings and make provisions as the bond becomes, in effect, a problem loan. Even if the bank could sell the bond into the market under such circumstances, it would be forced to take an outright loss. China’s major financial institutions, banks and insurance companies are all listed on overseas exchanges and audited by international firms. The need to take reserves should be unavoidable in such circumstances. China has not been, and will not be, exempt from such circumstances.

In short, China’s banks face severe challenges on three fronts. In addition to their structural exposures to the old NPL portfolios of the 1990s, there will inevitably be new NPLs arising out of their lending spree of 2009. Thirdly, the banks are fully exposed to both interest rate-related and credit-induced write-downs in the value of their fixed-income securities portfolios. In 2009, securities investments constituted 30 percent of the total assets of China’s Big 4 banks, or RMB7.2 trillion. While the interest risk of these portfolios can now be hedged somewhat as a result of the very recent emergence of a local-currency interest-rate swap market, for the state, it is a zero-sum game: BOC may effectively hedge, but its counterparty will almost inevitably be another state-owned bank. The effect of mark-downs, credit losses or even simply negative yields on bank capital would obviously be significant. From the viewpoint of the issuer, too, they seem to make little difference. In the international markets, corporations can source cheaper funds from other classes of investor; but in China, the banks remain the investor and the all-in cost to the issuer will be the same as a loan. So the question again presents itself: why did China build its fixed-income market?

ENDNOTES

1

A “repo” or “repossession” contract is a kind of financing transaction in which a party holding, most commonly, government bonds provides the bond as collateral to a second party who then lends money to the first party. This is a cheap way of funding a large bond portfolio.

2

For the only authoritative history of China’s government bond markets, see Jian Gao 2007.

3

This group is not the same as the primary-dealer group authorized by the MOF for CGB underwriting. The two non-banks are CITIC Securities and China International Capital Corporation. In late 2009, some foreign banks received licenses to underwrite financial bonds only to be told that “circumstances are not yet mature” for their active participation.