Pompeii (6 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

12. The House of the Faun was one of the grandest, and by the first century CE most old-fashioned, houses of the town, though it is now sadly dilapidated. Here we look through its front door into the main atrium, with the dancing satyr (or Faun). Beyond lay two large peristyle gardens and the famous Alexander Mosaic (Ill. 13).

However we imagine the column in its original setting, with beech trees few or many, woodland or artificial grove, the main lines of its story are clear enough. When the early shrine was eventually covered by housing, probably in the third century BCE, the standing column was preserved intact within the later structures, out of respect – or so we may guess – for its religious status. Centuries later, in 79 CE, it was still visible in the house that then stood on the plot: whether even at that date it retained some trace of special sanctity, or had simply become an interesting talking point for its owners in an otherwise nondescript house, we do not know.

The little story of this column is a reminder of a much bigger point: that by the time it was finally destroyed Pompeii was an old city, and visibly so. Although, to most modern eyes, the ruins appear homogeneously Roman, indistinguishable in date and style, they are in fact nothing of the sort. For a start, as we shall soon see, in 79 CE Pompeii had strictly speaking been a ‘Roman’ town for less than 200 years. But also, like most cities, ancient or modern, it was a sometimes messy amalgam of spanking-new building, esteemed antiques and artful restorations – as well as of the quaintly old-fashioned and the quietly dilapidated. Its residents would no doubt have been well aware of these differences and of the mixture of old and new that made up their town.

13. The most intricate ancient mosaic ever discovered, the Alexander Mosaic covered the floor of one of the main display rooms of the House of the Faun. This engraving shows the complete design. Alexander the Great (on the left) is fighting Darius the King of Persia. As his horses tell us (for they have already turned) Darius is about to flee in the face of the onslaught of the young Macedonian. There are all kinds of virtuoso artistic touches here – such as the horse in centre stage seen as if from behind. (See also Plate 15.)

The most extraordinary example of a ‘museum piece’ is one of the most famous, and now most visited, of all Pompeian houses: the House of the Faun. This house is vast, the biggest in the city, and at some 3000 square metres is of positively regal dimensions (approaching the scale, for example, of the palaces of the kings of Macedon at Pella in northern Greece). It is now known not only for its bronze statue of the dancing ‘faun’ but also for its stunning suite of decorated floor mosaics. Prime amongst these is the so-called ‘Alexander mosaic’ (Ill. 13), one of the star exhibits of the National Museum in Naples, and painstakingly constructed from a countless number of tiny stones or

tesserae

: estimates have varied from 1.5 million to 5 million, no one ever having had the patience to count them one by one. When first excavated in the 1830s, its epic proportions and confused mêlée of fighting prompted the ingenious idea that it depicted a battle scene from Homer’s

Iliad

. We are now convinced that it shows the defeat of the Persian king Darius (in his chariot, on the right; Plate 15) by the youthful Alexander the Great (on horseback, on the left) – perhaps, as is usually assumed, a virtuoso copy in mosaic of a lost masterpiece in painting, or perhaps an original creation.

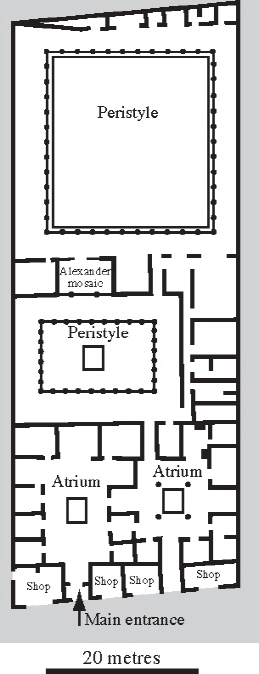

Figure 2.

The House of the Faun. Though vastly over-blown (covering a whole city block), the House of the Faun still shows many characteristic features of more ordinary Pompeian houses. The street frontage, for example, is occupied by a series of shops. This version of the standard plan takes the visitor through a narrow entrance way into one of two atria. Beyond lie two peristyle gardens.

Few modern visitors, who marvel at its size or admire its exquisite mosaics (there are nine others in the Naples Museum), realise quite how old-fashioned the House of the Faun would have seemed by the time of the eruption. The house was given its final form in the late second century BCE, when the mosaics were installed and many of its walls were grandly painted in the characteristic style of the time, and it remained more or less the same for the next 200 years. New paintings and restorations were done carefully to match. Who the rich owners of this house were we do not know (though one nice suggestion is that they were a longstanding local family, called Satrius – in which case that bronze faun or ‘satyr’ is a visual pun on their name). Still less do we know what encouraged (or forced) them to keep it unchanged over the centuries. What

is

clear is that the experience in 79 of visiting the House of the Faun would have been not so far different from our own experience of visiting a historic house or stately home. Passing through its portals – stepping over another mosaic, this time blazoning the Latin word

HAVE

, meaning ‘greetings’ (though the entirely unintended English pun on possession seems appropriate for this vast mansion) – you would have found yourself back in the second century.

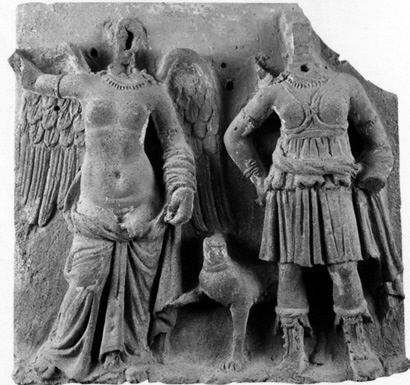

14. One of a series of terracotta reliefs (60 centimetres high) found re-used in the garden wall of the House of the Golden Bracelet – originally having adorned some sacred building, possibly the Temple of Apollo in the Forum. On this panel, the goddess Diana (Greek Artemis) stands on the right, and a figure of Victory on the left.

The House of the Faun is an extreme case. But all over the town the old was mixed up with the new. Distinctly old-fashioned styles of interior decor, for example, were lovingly preserved, or left to peel, next to the newest decorative fashions. The sundial in the exercise area of one of the main public baths, allowing busy bathers or exercisers to keep an eye on the time, was not only two centuries old by the time of the eruption, but it carried a commemorative inscription written in the native, pre-Roman language of the area – Oscan. By 79 probably only a few of Pompeii’s inhabitants could have deciphered that it had been paid for by the local council, using money they had accrued from fines.

We can also glimpse other stories of preservation and reuse to rival that of the Etruscan column. One recent discovery has revealed the ultimate fate of a series of terracotta sculptures which (to judge from their subject matter and shape) must once have adorned a temple in Pompeii itself or its surrounding countryside, possibly even the temple of the god Apollo in the Forum (Ill. 14). Crafted sometime in the second century BCE, and decommissioned perhaps after the earthquake of 62 CE, they ended up built into the garden wall of a rich multi-storey house (the House of the Golden Bracelet) which overlooked the sea – with what must have been stunning views – on the western edge of the town. A nice piece of architectural salvage maybe, though a far cry from the religious sanctity of their original location.

Before Rome

Pompeii was an even older city than its visible remains suggest. In 79, there was no building in use – public or private – that was earlier than the third century BCE. But at least two of the main temples of the city, even if repeatedly restored, rebuilt and brought up to date, had a history stretching back to the sixth century. The Temple of Apollo, in the Forum, was one, as was the Temple of Minerva and Hercules nearby. This seems to have been in ruins at the time of the eruption, and had possibly been abandoned once and for all, but excavations have brought to light some of the decorative sculpture from its earlier phases, pottery from the sixth century BCE and hundreds of offerings – many of them little terracotta figurines, some clearly representing the goddess Minerva (Greek Athena) herself. Besides, as the explorations around the Etruscan column show, digging down under the surviving structures elsewhere in the city can also produce evidence of much earlier occupation of the site.

One of the boom industries in the current archaeology of Pompeii is, in fact, the story of the town’s early history. The fashionable question for specialists has shifted from ‘What was Pompeii like in 79 CE?’ to ‘When did the city originate and how did it develop?’. This has launched a whole series of excavations deep under the first-century CE surface to discover what was on the site before the structures that we can still see. It is a fiendishly difficult process, not least because hardly anyone is keen to destroy the surviving remains simply to find out what they replaced. So most of the work has been ‘key-hole archaeology’, digging down in small areas, where it can be done with minimum damage to what lies above – and to the attractiveness of Pompeii for visitors. For most of us, let’s face it, come to see the impressive ruins of the city overwhelmed by Vesuvius, not the faint traces of some archaic settlement.

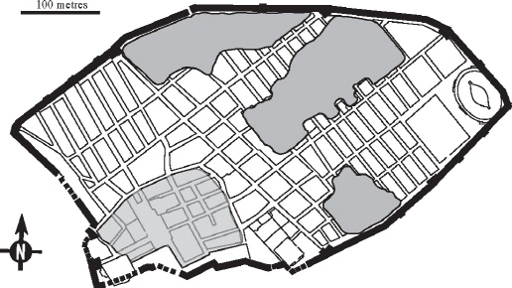

Figure 3.

The development of the city plan. The chronology of the city’s growth appears to be visible in the street plan. The ‘Old Town’ at bottom left (shaded) has an irregular street pattern. Other blocks of streets follow different alignments.

The challenge is to match up these isolated pockets of evidence both to each other and to the hints of the history of urban development given by the city’s ground plan. For it has long been recognised that the pattern of streets, with different areas having differently shaped ‘blocks’ and subtly different alignments, almost certainly reflects in some way the story of the city’s growth (Fig. 3). The other key fact is that the circuit of the town walls on their present line dates back to the sixth century BCE – meaning that (surprising as this may seem) the ultimate extent of the town was established from this early period.