Pompeii (9 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

The usual idea is that the people of Pompeii went on with their lives, untroubled, as the big events of Roman history unfurled; first as the free quasi-democratic Republic of Rome collapsed into dictatorship and bouts of civil war, until Augustus (31 BCE–14 CE) established the one-man rule of the Roman empire; then later as one emperor succeeded the next, some like Augustus himself or Vespasian (who came to the throne, after another bout of civil war, in 69 CE) gaining a reputation for probity and benevolent autocracy, others like Caligula (37–41 CE) or Nero (54–68 CE) decried as mad despots. For the most part the centre of action remained a long way from Pompeii, though occasionally it came a little too close for comfort. In the late 70s BCE, for example, not long after the foundation of the colony, the slave rebels under Spartacus temporarily made their encampment in the crater of Vesuvius, just a few kilometres to the north of the town. This is an incident perhaps immortalised in a rough painting discovered in a house at Pompeii under layers of later decoration which shows a scene of combat including a man on horseback labelled, in Oscan, ‘Spartaks’. It is a nice idea. But more likely the painting shows some kind of gladiatorial fight.

Very occasionally, too, Pompeii itself made an impact on the capital and on Roman literature, whether because of some natural disaster, or because of what happened in 59 CE. In that year some gladiatorial games got out of hand, a murderous fight ensued between the local inhabitants and the ‘away supporters’ from nearby Nuceria, and the wounded and bereaved ended up taking their complaints to the emperor Nero himself. By and large, however, the usual line is that life in Pompeii went on its sleepy way, without making much of a dent on life and literature at Rome – or, vice versa, without being much affected by international geopolitics and the machinations of the elite in the capital.

In fact, Cicero could even joke about the doziness of local Pompeian politics. On one occasion, he was attacking the way that Julius Caesar would appoint anyone of his favourites to the senate, without the usual processes of election. In a quip reminiscent of all those modern disparaging references to Tunbridge Wells or South Bend, Indiana, he is supposed to have said that while it was easy enough to get into the senate at Rome, ‘at Pompeii it is difficult’. Eager students of Pompeian local government have sometimes seized on this to argue that the political life of the town really was buzzing with competition, even more so than Rome itself. But they have missed the heavy irony. Cicero’s point is along the lines of ‘It’s easier to get into the House of Lords than to be mayor of Tunbridge Wells’ – in other words, it is even easier than the easiest thing you can think of.

Archaeologists have greeted the insignificance of Pompeii in two ways. Most have, openly or privately, lamented the fact that the single town in the Roman world to have been preserved at this level of detail should be one so far from the mainstream of Roman life, history and politics. Others, by contrast, have celebrated the fact that the city is so unremarkable, seeing it as a bonus that we here get a glimpse of those inhabitants of the ancient world who are usually unnoticed by history. No deceptive Hollywood-style glamour here.

But Pompeii was by no means the forgotten backwater that it is usually painted. True, it was not Rome; and, to follow Cicero, its political life (as we shall see in Chapter 6) can hardly have been as cut-throat as that in the capital. It was in many ways a very

ordinary

place. But it is a feature of ordinary places in Roman Italy that they had close bonds to Rome itself. They were often linked by ties of patronage, support and protection to the highest echelons of the Roman elite. We know, for example, from an inscription that once adorned his statue in the town, that the emperor Augustus’ favourite nephew and would-be heir, Marcellus, at one point held the semi-official position of ‘patron’ of Pompeii. The histories of communities like this were bound up with that of Rome. They provided a stage on which the political dramas of the capital could be replayed. Their successes, problems and crises were capable of making an impact well beyond the immediate locality, in the capital itself. To put it in the jargon of modern politics, Roman Italy was a ‘joined up’ community.

Pompeii lay just 240 kilometres south of Rome, linked to it by good roads. An urgent message – provided the messenger had enough changes of mount – could reach Pompeii from the capital in a day. For ordinary travel, you would allow three days, a week at dawdling pace. But it was not just that, in ancient terms, Pompeii was easily accessible from the capital. The Roman elite, and their entourages, had good reason to make the journey. For the Bay of Naples, then as (in parts) still now, was a popular area of relaxation, holiday-making and often luxurious ‘second homes’ in the lush countryside or, best of all, overlooking the sea. The town of Baiae, across the Bay from Pompeii, had become by the first century BCE a byword for an upmarket, hedonistic resort – more or less the ancient equivalent of St Tropez. We have already spotted the young Cicero, serving as a raw recruit in the siege of Pompeii during the Social War. Twenty-five years later, he acquired – for slightly more than he could afford – a country residence ‘in the Pompeii area’, which he used as a bolt-hole away from Rome and, while he vacillated in the run-up to the Civil War between Julius Caesar and Pompey the Great in 49 BCE, as a convenient place from which to plan his getaway by sea. Eighteenth-century scholars were convinced that they had identified the very building, in a substantial property just outside Pompeii’s Herculaneum Gate (and since covered over again) (Plate 1). Based on a minute analysis of all Cicero’s references to his ‘Pompeianum’ and combined with a good deal of wishful thinking, their identification is – sadly – almost certainly wrong.

Their twentieth-century followers became almost equally excited about pinpointing the property of another grandee in the area near the city: this time, Nero’s second wife, Poppaea, the celebrity beauty for whom the emperor killed both his mother and his first wife, Octavia, and who was herself eventually to die at her husband’s hands, inadvertently (he kicked her in the stomach while she was pregnant, but had not meant to kill her). As with Cicero, we have clear evidence that she was a local proprietor. In this case, some legal documents discovered in the nearby town of Herculaneum record ‘the empress Poppaea’ as owner of some brick- or tile-works ‘in the Pompeii area’. Her family may have come from Pompeii itself, and it has even been suggested that they were the owners of the large House of the Menander. Although it is nowhere directly stated in any of the ancient discussions of Poppaea’s (bad) character and background, the brickworks, combined with plenty of evidence in the town for a prominent local family of ‘Poppaei’, makes her Pompeian origin quite likely.

That is enough on its own to illustrate again the strong connections between this area and the world of the Roman elite, but the temptation to find the remains of Poppaea’s local residence has proved just too strong, even for hard-headed modern archaeologists. The prime candidate is the vast villa at Oplontis (modern Torre Annunziata, some eight kilometres from Pompeii). Perhaps it was hers; for it is a very large property, on an imperial scale. But, despite the fact that it is now regularly called the ‘Villa of Poppaea’ as if that were certain, the evidence is extremely flimsy, hardly going beyond a couple of ambiguous graffiti, which do not necessarily have any link with Poppaea or Nero at all. Take the name of ‘Beryllos’, for example, scratched on one of the villa walls. That may, but just as easily may not, refer to the Beryllos who is known from one reference in the Jewish historian Josephus to have been one of the slaves of Nero. Beryllos was a common Greek name.

Connections of a different kind between Pompeii and Rome are seen in the account of what is for us the second most famous appearance of Pompeii (after the eruption itself) in the narrative of Roman history: that riot in the Amphitheatre in 59, as described by the Roman historian Tacitus:

About the same time, there was a minor skirmish between the men of Pompeii and Nuceria, both Roman colonies, which turned into a ghastly massacre. It happened at a gladiatorial show given by Livineius Regulus, whose expulsion from the senate I discussed above. In the unruly way of these inter-town rivalries, they moved from abuse, to pelting each other with stones, until they finally drew swords. The Pompeians had the advantage, because it was in their town that the show was being put on. So many Nucerians were taken off to Rome, with their terrible injuries and mutilations, and there were also many who lamented the deaths of their children or parents in the affray. The emperor instructed the senate to clear the matter up; the senate referred it to the consuls. When it came back to the senate again, the Pompeians were forbidden from holding any public gathering of that kind for ten years, and their illegal clubs were disbanded. Livineius and the others who had stirred up the trouble were punished with exile.

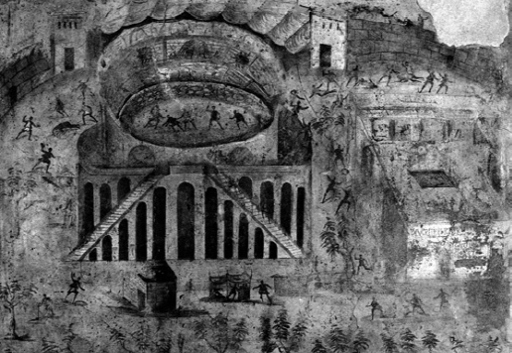

16. This painting shows the riot in the Amphitheatre in 59 CE in full swing. The Amphitheatre itself on the left is carefully depicted, with its steep external staircase, the awning over the arena and a variety of stalls set up outside. On the right the fighting is spreading to the next door exercise ground or

palaestra

.

Amongst those exiled with Livineius, were the serving

duoviri

of Pompeii; or that at least is a reasonable inference from the fact that the names of

two

pairs of these officials are known for this year.

This story is made even more memorable because a painting survives from the town, in which for some reason – jingoistic lack of repentance, perhaps? – the artist has chosen (or been instructed) to illustrate the notorious event (Ill. 16). What might at first sight appear to be gladiators fighting inside the arena are presumably the rioting Pompeians and Nucerians, who are also doing battle around the outside of the building.

Modern, as much as Roman, obsession with gladiatorial culture has put this incident centre-stage. But there is more to Tacitus’ account than a vivid glimpse of a gladiatorial display gone wrong. He notes, for example, that the Pompeian show in question was given by a disgraced Roman senator, who had been expelled from the senate some years earlier (frustratingly, the portion of the narrative where Tacitus discusses this ‘above’ no longer survives). It is hard, however, to resist the conclusion that a rich man, out of favour in Rome itself, was looking to Pompeii as a place where he could play the part of benefactor and grandee. More than that, it is hard not to wonder whether there was some connection between the shady, and perhaps controversial, sponsor of the show and the violence that it sparked. Tacitus also hints here at the ways in which the local communities might be able to foster interest in their own problems at Rome. For it is clear that the Nucerians (though in other circumstances it might have been the Pompeians) could go off to the capital and get the emperor himself to take notice and initiate a practical response. How they met him (if they did) is not stated. But this is where a Roman ‘patron’ of a town (like Marcellus at Pompeii) would come in, either arranging for his ‘clients’ an audience with the emperor or with one of his officials, or perhaps more likely taking up the case on their behalf. The rule was that local Italian issues did matter at Rome; the imperial palace was, in principle at least, open to their delegations.

This kind of delegation to Rome may lie behind a later intervention by an emperor into the affairs of Pompeii. A series of inscriptions have been found outside the gates of the city, recording the work of an agent of Vespasian, an army officer by the name of Titus Suedius Clemens, who ‘made an inquiry into the public land appropriated by private individuals, carried out a survey and restored them to the town of Pompeii’. What lies behind this is a common cause of dispute in the Roman world: state-owned land illegally occupied by private owners, followed by the efforts of the state (whether Rome or a local community) to recover it. In this case, some historians have suspected a spontaneous intervention by the new emperor Vespasian, who seems to have played the part of a new broom in the matter of imperial finances. More likely the local council of Pompeii had approached the emperor, as the Nucerians had earlier, asking for his help in recovering their state property and this Clemens had been dispatched. A long-serving army professional, he had played an inglorious part in the civil wars that ushered in Vespasian’s rule, written up by Tacitus as a trigger-happy NCO, ready to trade in proper standards of military discipline in return for popularity with his men. Whether he was a reformed character by the time he arrived to sort out Pompeii’s land disputes, we can only hope. But he certainly interfered (by request or not) rather more extensively in the town’s affairs. A number of notices survive in which his public support is paraded for one of the candidates in the forthcoming elections: ‘Please elect Marcus Epidius Sabinus as

duumvir

with judicial power, backed by Suedius Clemens.’ How long he was active in the city, again we do not know, but he seems to have escaped the eruption. In November of 79 CE we find him carving his name on the so-called ‘singing statue of Memnon’ (in fact a colossal statue of a pharaoh, which produced a strange sound at daybreak), a Roman tourist hot-spot deep in Egypt.