Pompeii (5 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

We have likewise given modern names to the town gates, calling them after the place or direction they faced: the Nola Gate, the Herculaneum Gate, the Vesuvius Gate, the Marine Gate (towards the sea) and so on. In this case, we have a rather clearer idea of what the ancient names might have been. What we call Herculaneum Gate, for example, was to the Roman inhabitants the Porta Saliniensis or Porta Salis, that is ‘Salt Gate’ (after the nearby saltworks). Our Marine Gate may well have been called the Forum Gate, or so a few scraps of ancient evidence combined with some plausible modern deduction suggest; after all, it not only faced the sea, but it was also the closest gate to the Forum.

In the absence of ancient addresses, modern gazetteers to the city use a late nineteenth-century system for referring to individual buildings. The same archaeologist who perfected the technique of casting the corpses, Giuseppe Fiorelli (one-time revolutionary politician, and the most influential director of the Pompeian excavations ever), divided Pompeii into nine separate areas or

regiones

; he then numbered each block of houses within these areas, and went on to give every doorway onto the street its own individual number. So, in other words, according to this now standard archaeological shorthand, ‘VI.xv.I’ would mean the first doorway of the fifteenth block of region six, which lies at the north-west of the city.

To most people, however, VI.xv.I is better known as the House of the Vettii. For, in addition to that bare modern numeration, most of the larger houses at least, as well as the inns and bars, have gained more evocative titles. Some of these go back to the circumstances of their first excavation: the House of the Centenary, for example, was uncovered exactly 1800 years after the destruction of the city, in 1879; the House of the Silver Wedding, excavated in 1893, was named in honour of the twenty-fifth wedding anniversary of King Umberto of Italy, celebrated in that same year – the house, ironically, being now better known than the royal marriage. Other names reflect particularly memorable finds: the House of the Menander is one; the House of the Faun another, named after the famous bronze dancing satyr, or ‘faun’, found there (Ill. 12), (its earlier name, the House of Goethe, went back to the son of the famous Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who witnessed part of the excavation in 1830 very shortly before he died – but his sad story proved rather less memorable than the spritely sculpture). Very many, however, like the House of the Vettii, have been named after their Roman occupants, as part of that much bigger project of repopulating the ancient town, and of matching up the material remains to the real people who once owned them, used them or lived in them.

This is an exciting, if sometimes dodgy, procedure. There are cases where we can be sure that we have made the right match. The house of the banker Lucius Caecilius Jucundus, for example, is almost certainly identified by his banking archives, which had been stored in the attic. Aulus Umbricius Scaurus, the most successful local manufacturer of

garum

(that characteristically Roman concoction of decomposing marine life, euphemistically translated as ‘fish sauce’), left his mark and his name on his own elegant property – with a series of mosaics, featuring jars of the stuff labelled with such slogans as ‘Fish sauce, grade one, from Scaurus’ manufactory’ (Ill. 57). The House of the Vettii, with its exquisite frescoes, has been confidently assigned to a pair of (probably) ex-slaves, Aulus Vettius Conviva and Aulus Vettius Restitutus. This is on the basis of two seal stamps and a signet ring with those names found in the front hall, plus a couple of election posters, or at least their ancient equivalent, painted up on the outside of the house (‘Restitutus is canvassing for ... Sabinus to be aedile’) – and on the assumption that another seal stamp found in another part of the house, this time naming Publius Crustius Faustus, belonged to some tenant living on the upper floor.

In many cases the evidence is far flimsier, relying on perhaps a single signet ring (which, after all, could just as easily have been dropped by a visitor as the owner), a name painted on a wine jar, or a couple of graffiti signed by the same person, as if graffiti artists always chose to write on their own home walls. One particularly desperate deduction has come up with the name of the man who owned the brothel in the town, and the high-spot for many modern as no doubt ancient visitors: it is Africanus. This is an argument based largely on a sad message scratched, by a client most likely, on the wall of one of the girls’ booths. ‘Africanus is dead’ (or literally ‘is dying’), it reads. ‘Signed young Rusticus, his school mate, grieving for Africanus’. Africanus, to be sure, may have been a local resident: or so we might guess from the fact that on a wall close-by someone of that name pledged their support in the local elections to Sabinus (the same candidate who had won Restitutus’ vote). But there is no reason at all to imagine that young Rusticus’ expression of post-coital misery, if that is what it was, was making any reference at all to the owner of the brothel.

The end result of this and other such over-optimistic attempts to track down the ancient Pompeians and put them back into their houses, bars and brothels is obvious: in the modern imagination, an awful lot of Pompeians have ended up in the wrong place. Or, to put it more generally, there is a large gap between ‘our’ ancient city and the city destroyed in 79 CE. In this book, I shall consistently be using the landmarks, finding aids and terminology of ‘our’ Pompeii. It would be confusing and irritating to give the Herculaneum Gate its ancient name of ‘Porta Salis’. The numeration invented by Fiorelli allows us quickly to pinpoint a location on a plan, and I shall be using it in the reference sections. And, incorrect as some of them may be, the famous names – House of the Vettii, House of the Faun, and so on – are much the easiest way of bringing a particular house or location to mind. Yet, I shall also be exploring that gap in more detail, thinking about how the ancient city has been turned into ‘our’ Pompeii, and reflecting on the processes by which we make sense of the remains that have been uncovered.

In stressing those processes, I am being both up to the minute and, in a sense, returning to a more nineteenth-century experience of Pompeii. Of course, nineteenth-century visitors to the city, like their twenty-first-century counterparts, enjoyed the illusion of stepping back in time. But they were also intrigued by the ways in which the past was revealed to them: the ‘how’ as well as the ‘what’ we know of Roman Pompeii. We can see this in the conventions of their favourite guidebooks to the site, above all Murray’s

Handbook for Travellers in Southern Italy

, first published in 1853 to cater for the beginning of mass tourism (rather than Grand Tourists) to the site. The railway line had opened in 1839 and became the favoured method of transport for visitors, and they were serviced by a tavern near the station where they could take lunch after their exertions among the ruins. This was a place of fluctuating fortunes (in 1853 it supposedly had ‘a very civil and obliging landlord’, by 1865 readers were recommended not to tuck in without coming to ‘an agreement as to the charge beforehand with mine host’). But it was the germ of the vast industry of snacks, fruit and, especially, bottled water that now dominates the outskirts of the site.

Murray’s

Handbook

repeatedly engaged these Victorian visitors with the problems of interpretation, sharing the various competing theories about what some of the major public buildings that had been discovered were for. Was the building we call the

macellum

(market), in the Forum, really a market? Or was it a temple? Or was it a combination of a shrine and a café? (As we shall see, many such questions of function have not yet been resolved, but modern guidebooks tend to deprive their readers of – they would say spare them – the problems and controversies.) They are even careful to note, along with the description of each ancient building, the date and circumstances of its rediscovery. It is as if those early visitors were supposed to keep two chronologies running in their heads at the same time: on the one hand, the chronology of the ancient city itself and its development; on the other, the history of Pompeii’s gradual re-emergence into the modern world.

We might even imagine that the famous stunts in which dead bodies or other notable finds were conveniently ‘discovered’, just as visiting dignitaries happened to be passing, were another aspect of the same preoccupations. We tend now to laugh at the crudeness of these charades and the gullibility of the audience (could visiting royalty have been so naive as to imagine that such wondrous discoveries just happened to be made at the very moment of their own arrival?). But, as often, the tricks of the tourist trade reveal the hopes and aspirations of the visitors as much as they expose the guile of the locals. Here the visitors wanted to witness not just the finds themselves, but the processes of excavation that brought the past to light.

These are some of the issues that I wish to bring back into the frame.

A city of surprises

Pompeii is full of surprises. It makes even the most hard-nosed and well-informed specialists rethink their assumptions about life in Roman Italy. A large pottery jar with a painted label advertising its contents as ‘Kosher

Garum

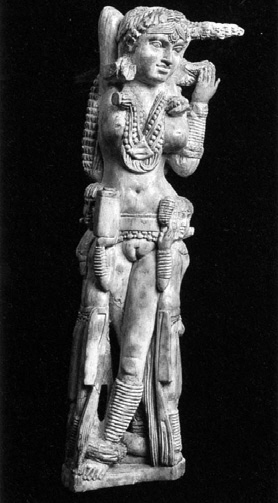

’ reminds us that men like Umbricius Scaurus might be looking to serve the niche market of the local Jewish community (with a guarantee of no shellfish among the now unrecognisable ingredients of that rotten concoction). A wonderful ivory statuette of the Indian goddess Lakshmi, found in 1938 in a house now called after it ‘The House of the Indian Statuette’, encourages us to think again about Rome’s connections with the Far East (Ill. 11). Did it come via a Pompeian trader, a souvenir of his travels? Or maybe via the trading community of Nabataeans (from modern Jordan) who lived at nearby Puteoli? Almost equally unexpected was the recent discovery of a monkey’s skeleton scattered, unrecognised by earlier excavators, among the bones in the storerooms on the site. An exotic pet perhaps – or, more likely, a performing animal, in street-theatre or circus, trained to amuse.

11. This ivory statuette of the Indian goddess Lakshmi offers a glimpse of the wide multicultural links of Pompeii. Goddess of fertility and beauty, she is depicted nearly naked apart from her lavish jewels.

It is a city of the unexpected, simultaneously very familiar to us and very strange indeed. A town in provincial Italy, with horizons no further than Vesuvius, it was at the same time part of an empire that stretched from Spain to Syria, with all the cultural and religious diversity that empires so often bring. The famous words ‘Sodom’ and ‘Gomora’ written in large letters on the walls of the dining room of a relatively modest house on the Via dell’Abbondanza (assuming that they are not the gloomy observation of some later looter) give us more than an eyewitness comment – or joke – on the morality of Pompeian social life. They remind us that this was a place in which the words of the Book of Genesis (‘Then the Lord rained upon Sodom and Gomorrah brimstone and fire from the Lord out of heaven’) as well as the works of Virgil must have rung a bell with at least some inhabitants.

A small-town community with – once we leave the women, children and slaves out of the equation – a citizen body of just a few thousand men, no bigger than a village or the student union of a small university, it nonetheless has a more forceful impact on the mainline narrative of Roman history than we tend to imagine. As we shall see in Chapter 1.

Glimpses of the past

Down a quiet back street in Pompeii, not far from the city walls to the north and just a few minutes’ walk from the Herculaneum Gate, is a small and unprepossessing house now known as the House of the Etruscan Column. Unremarkable from the outside and off the beaten track both in the ancient world and now, it conceals, as its modern name hints, a puzzling curiosity within. For lodged in the wall between two of its main rooms is an ancient column, its appearance reminiscent of the architecture of the Etruscans – who were a major power in Italy through the sixth and fifth centuries BCE, before the rise of Rome itself, with influence and settlements extending far beyond their homeland in north Italy to the area around Pompeii. The column almost certainly dates from the sixth century BCE, several hundred years before the house was built.

Careful digging under the house has thrown some light on this puzzle. It turns out that the column is in its original position and the house has been built around it. Part of a sixth-century BCE religious sanctuary, it was not a support for a building, but freestanding, possibly next to an altar and once carrying a statue (an arrangement known in other early religious sites in Italy). Sixth-century Greek pottery, presumably from offerings and dedications, was found in the area round about, as was evidence (in the form of seeds and pollen) for a significant number of beech trees. These were not likely to be natural woodland; for beech trees, it is argued, do not grow naturally on low ground in southern Italy. The speculation is, therefore, that this venerable old sanctuary had originally been surrounded by another of those characteristic features of early Italian religion: a sacred grove, here specially planted in beech. And by way of confirmation (rather weak confirmation, in my view) we are asked to compare a similarly ancient sanctuary of the god Jupiter in Rome, set in its own sacred beech grove: the ‘Fagutal’ as it was called, from

fagus

meaning beech tree.