Pompeii (2 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

3. Someone’s precious possession? This squat little figurine made out of red amber from the Baltic was found with one of the unsuccessful fugitives. Just 8 centimetres tall, it was perhaps meant to represent one of the stock characters from Roman mime, popular entertainment in Pompeii.

We can trace many other stories of attempted flight. Almost 400 bodies have been discovered in the layers of pumice, and nearer 700 in the now solid remains of the pyroclastic flow – many of these recaptured vividly at the moment of their death by the clever technique, invented in the nineteenth century, of filling the space left by their decomposing flesh and clothes with plaster, to reveal the hitched-up tunics, the muffled faces, the grim expressions of the victims (Ill. 2). One group of four, found in a street near the Forum, was probably an entire family trying to make its escape. The father went in front, a burly man, with big bushy eyebrows (as the plaster cast reveals). He had pulled his cloak over his head, to protect himself from falling ash and debris, and carried with him some gold jewellery (a simple finger-ring and a few ear-rings), a couple of keys and, in this case, a reasonable amount of cash, at almost 400

sesterces

. His two small daughters followed, while the mother brought up the rear. She had hitched up her dress to make the walking easier, and was carrying more household valuables in a little bag: the family silver (some spoons, a pair of goblets, a medallion with the figure of Fortuna, a mirror) and a small squat figurine of a little boy, wrapped up in a cloak, his bare feet peeking out at the bottom (Ill. 3). It is a crude piece of work, but it is made out of amber, which must have travelled many hundreds of kilometres from the nearest source of supply in the Baltic; hence its prize status.

Other finds tell of other lives. There was the medical man who fled clutching his box of instruments, only to be overwhelmed by the lethal surge as he crossed the

palaestra

(the large open space or exercise area) near the Amphitheatre, making for one of the southern gates in the city; the slave found in the garden of a large house in the centre of town, his movement surely hampered by the iron bands around his ankles; the priest of the goddess Isis (or maybe a temple servant) who had parcelled up some of the temple’s valuables to take with him in his flight, but had not gone more than 50 metres before he too was killed. And then, of course, there was the richly jewelled lady found in one of the rooms in the gladiators’ barracks. This has often been written up as a nice illustration of the penchant of upper-class Roman women for the brawny bodies of gladiators. Here, it seems, is one of them caught in the wrong place at the wrong time, her adultery exposed to the gaze of history. It is, in fact, a much more innocent scene than that. Almost certainly the woman was not on a date at all, but had taken refuge in the barracks, when the going got too rough on her flight out of the city. At least, if this

was

an assignation with her toy-boy, it was an assignation she shared with seventeen others and a couple of dogs – all of whose remains were found in the same small room.

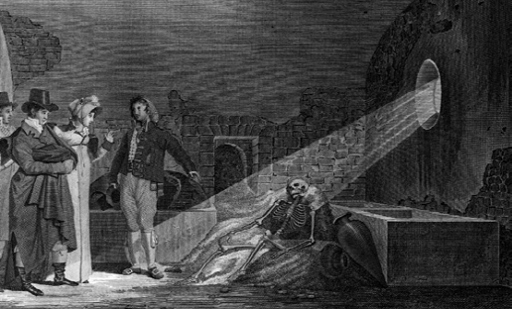

The dead bodies of Pompeii have always been one of the most powerful images, and attractions, of the ruined city. In the early excavations during the eighteenth and nineteeth centuries, skeletons were conveniently ‘discovered’ in the presence of visiting royalty and other dignitaries (Ill. 4). Romantic travellers gushed at the thought of the cruel disaster that had afflicted the poor souls whose mortal remains they witnessed, not to mention the more general reflections on the perilous fragility of human existence that the whole experience prompted. Hester Lynch Piozzi – the English writer who owed her surname to her marriage to an Italian music teacher – captured (and lightly parodied) these reactions, after a visit to the site in 1786: ‘How dreadful are the thoughts which such a sight suggests! How horrible the certainty that such a scene might be all acted over again tomorrow; and that, who today are spectators, may become spectacles to travellers of a succeeding century, who mistaking our bones for those of the Neapolitans, may carry them to their native country back again perhaps.’

4. Celebrity visitors to Pompeii had excavations re-staged for their benefit. Here, in 1769, the Emperor of Austria surveys a skeleton found in a house, now known after him as ‘The House of Emperor Joseph II’. The lady of the party reacts with more obvious interest.

In fact, one of the most celebrated objects from the first years of digging was the imprint of a woman’s breast found in a large house (the so-called Villa of Diomedes) just outside the city walls in the 1770s. Almost a century before the technique of making full plaster casts of the body cavities had been perfected, the solid debris here allowed the excavators to see the full form of the dead, their clothing, even their hair, moulded into the lava. The only part of this material they managed successfully to extract and preserve was that one breast, which was put on display in the nearby museum, and quickly became a tourist attraction. In due course it also became the inspiration for Théophile Gautier’s famous novella of 1852,

Arria Marcella

. This features a young Frenchman who, infatuated with the breast that he has seen in the museum, returns to the ancient city (in an unsettling combination of time travel, wishful thinking and fantasy) to find, or to reinvent, his beloved – the woman of his dreams, one of the last Roman occupants of the Villa of Diomedes. Sadly the breast itself, despite all its celebrity, has simply disappeared, and a major hunt for it in the 1950s failed to reveal any hint of its fate. One theory is that the battery of invasive tests carried out by curious nineteenth-century scientists eventually caused it to disintegrate: ashes to ashes, as it were.

The power of the Pompeian dead has lasted into our own age too. Primo Levi’s poem ‘The Girl-Child of Pompei’ uses the plaster cast of a little girl, found clutching her mother (‘As though, when the noon sky turned black / You wanted to re-enter her’), to reflect on the fate of Anne Frank and an anonymous schoolgirl from Hiroshima – victims of manmade rather than natural disasters (‘The torments heaven sends us are enough / Before your finger presses down, stop and consider’). Two casts even play a cameo role in Roberto Rossellini’s 1953 film,

Voyage to Italy

– hailed as ‘the first work of modern cinema’, though a commercial disaster. Clinging to each other, lovers still in death, these victims of Vesuvius serve as a sharp and upsetting reminder to two modern tourists (Ingrid Bergman – then herself in a faltering marriage to Rossellini – and George Sanders) of just how distant and empty their own relationship has become. But it is not only human victims who are preserved in this way. One of the most famous, and evocative, casts is that of a guard dog found still tethered to his post in the house of a wealthy fuller (laundry-man-cum-cloth-worker). He died frantically trying to get free of his chain.

Voyeurism, pathos and ghoulish prurience certainly all contribute to the appeal of these casts. Even the most hard-nosed archaeologists can come up with lurid descriptions of their death agonies, or of the toll taken on the human body by the pyroclastic flow (‘their brains would have boiled ...’). For visitors to the site itself, where some of the casts are still on display near where they were found, they produce something like the ‘Egyptian Mummy effect’: small children press their noses against the glass cases with cries of horror, while adults resort to their cameras – though hardly disguising their similarly grim fascination with these remains of the dead.

But ghoulishness is not the whole story. For the impact of these victims (whether fully recast in plaster, or not) comes also from the sense of immediate contact with the ancient world that they offer, the human narratives they allow us to reconstruct, as well as the choices, decisions and hopes of real people with whom we can empathise across the millennia. We do not need to be archaeologists to imagine what it would be like to abandon our homes with only what we could carry. We can feel for the doctor who chose to take the tools of his trade with him, and almost share his regret at what he would have left behind. We can understand the vain optimism of those who slipped the front-door keys in their pockets before taking to the road. Even that nasty little amber figurine takes on special significance, when we know that it was someone’s precious favourite, snatched up as they left home for the last time.

Modern science can add to these individual life stories. We can go one better than earlier generations in squeezing all kinds of personal information out of the surviving skeletons themselves: from such relatively simple calibrations as the height and stature of the population (ancient Pompeians were, if anything, slightly taller than modern Neapolitans) through tell-tale traces of childhood illnesses and broken bones, to hints of family relationships and ethnic origin that are beginning to be offered by DNA and other biological analysis. It is probably pushing the evidence too far to claim, as some archaeologists have done, that the particular development of one teenage boy’s skeleton is enough to show that he had spent much of his short life as a fisherman and that the erosion of his teeth on the right hand side of his mouth was caused by biting on the line which held his catch. But elsewhere we are on firmer ground.

In two back rooms of one substantial house, for example, the remains of twelve people were discovered, the owner, presumably, with his family and slaves. Six children and six adults, they included a girl in her late teens, who had been nine months pregnant when she died, the bones of her foetus still lying in her abdomen. It may well have been her late pregnancy that encouraged all of them to take shelter inside, hoping for the best, rather than risk a hasty escape. The skeletons have been none too carefully preserved since their discovery in 1975 (the fact that, as one scientist has recently reported, ‘the lower premolars [of one skull] had been erroneously glued into the sockets of the upper central incisors’ is not evidence of ham-fisted ancient dentistry, but of ham-fisted modern restoration). Nonetheless, by piecing together various clues that remain – the relative ages of the victims, the rich jewels on the pregnant girl, the fact that she and a nine-year-old boy suffer from the same minor, genetic spinal disorder – we can begin to build up a picture of the family who lived in the house. An elderly couple, he in his sixties, she around fifty with clear signs of arthritis, were very likely the house owners, as well as the parents, or grandparents, of the pregnant girl. From the quantity of jewellery she was wearing we can be fairly sure that she was not a slave, and the shared spinal problem hints that she was a relative of the family by blood rather than marriage – the nine-year-old boy being her younger brother. If so, then she and her husband (probably a man in his twenties, whose head, so the skeleton suggests, had a pronounced, disfiguring and no doubt painful tilt to the right) either lived with her family, or had moved back to her home for the birth, or of course just happened to be visiting on the fatal day. The other adults, a man in his sixties and a woman in her thirties, may just as well have been slaves as relatives.

A close look at their teeth, reglued or not, adds further details. Most of them have a series of tell-tale rings in the enamel that come from repeated bouts of infectious diseases during childhood – a nice reminder of the perilous nature of infancy in the Roman world, when half those born would have died before they were ten. (The better news was that if you made it to ten, you could expect to live another forty years, or more.) The clear presence of tooth decay, even if below modern Western levels, points to a diet with plenty of sugar and starch. Of the adults, only the husband of the pregnant girl had no sign of decay. But he, again to judge from the state of his teeth, had fluoride poisoning, presumably having grown up outside Pompeii, in some area with unusually high levels of natural fluoride. Most striking of all, every single skeleton, even the children, had large build-ups – in some cases a couple of millimetres – of calculus. The reason for this is obvious. Toothpicks there may have been, even some clever concoctions for polishing and whitening the teeth (in a book of pharmacological recipes, the emperor Claudius’ private doctor records the mixture which is said to have given the empress Messalina her nice smile: burnt antler-horn, with resin and rock-salt). But this was a world without toothbrushes. Pompeii must have been a town of very bad breath.

A city disrupted

Women about to give birth, dogs still tethered to their posts, and a decided whiff of halitosis ... These are memorable images of normal, everyday life in a Roman town suddenly interrupted in midstream. There are plenty more: the loaves of bread found in the oven, abandoned as they baked; the team of painters who scarpered in the middle of redecorating a room, leaving behind their pots of paint and a bucketful of fresh plaster high up on a scaffold – when the scaffold collapsed in the eruption, the contents of the bucket splashed right across the neatly prepared wall, leaving a thick crust still visible today. But scratch the surface, and you find that the story of Pompeii is more complicated, and intriguing. In many ways Pompeii is not the ancient equivalent of the

Marie Céleste

the nineteenth-century ship mysteriously abandoned, the boiled eggs still (so it was said) on the breakfast table. It is not a Roman town simply frozen in midflow.