Luftwaffe Fighter Aces (6 page)

Read Luftwaffe Fighter Aces Online

Authors: Mike Spick

The third reason is conjectural, but it seems probable that, Spanish experience notwithstanding,

JGr 102

used the wrong tactics! Almost certainly they stayed and mixed it with

GCII/5

instead of using the much safer dive and zoom. The reason for this was probably overconfidence, born of experience in Poland and the dogfighting tradition of the Great War. Gentzen, as the ranking

Luftwaffe Experte

(Spain was of course

Legion Kondor,

not

Luftwaffe)

, would have zealously been trying to maintain his lead. The ‘fangs out, hair on fire’ syndrome is widely known among fighter pilots of all nations and all periods and has led many a budding ace to overreach himself. In fact such rashness was not confined to the

Jagdflieger,

in both Poland and France there were several recorded instances of German bombers attacking enemy fighters!

A further factor was that, at this stage, many

Geschwader

were still led by ‘old eagles’ of the Great War, men such as

Ritter

Eduard von Schleich and Theo Osterkamp, who imposed their own tactical ideas on their units and whose exploits were worthy of emulation. Certainly, from British and French accounts of the period, the

Jagdflieger

showed no disinclination to dogfight. Their first clash with the RAF came on 22 December when

III/JG 53

accounted for two Hurricanes of No 73 Squadron, one of which fell to Mölders.

Flying was restricted that winter by particularly bad weather, and months passed with no more than occasional skirmishes in what had become known as the ‘Phoney War’ or

‘Sitzkrieg’.

But restricted opportunities or no, many future high-scoring

Experten

opened their accounts during this period. Amongst them were Heinz Baer (with a final total of 220 victories), who as an NCO pilot claimed his first victory, a Hawk 75, on 29 September; Anton Hackl (192); Max Stötz (189); Wolf

Dietrich Wilcke (162); Joachim Müncheberg (135); and Erich Leie (118). The

‘Sitzkrieg’

did, however, give

l’ A

rmée de l’ Air

time to expand and re-equip its fighter force. By the beginning of May 1940 two new types were entering service, the Bloch MB.151/152 and, best of all, the Dewoitine D.520, although the latter only appeared in small numbers before the surrender. See

Table 3

.

The uneasy calm was broken on the morning of 10 May 1940. To invade France, Germany had to circumvent the strongly fortified Maginot Line which protected the French border. They bypassed it, violating the neutrality of Belgium and Holland with airborne forces and fast-moving armoured columns. Protected and preceded by the

Luftwaffe,

they streamed south-west. The numerically weak and poorly equipped Dutch and Belgian air forces were overwhelmed and largely destroyed on the ground. This treacherous attack was accompanied by heavy bombing raids on French airfields at Dijon, Lyons, Metz, Nancy and Romilly, and against major communications centres in France.

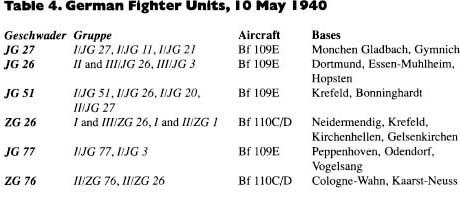

The

Luftwaffe

had 860 Bf 109s and 350 Bf 110s to clear the way for their 1,680 level and dive bombers (see

Table 4

). Against this armada

l

’ Armée de l’ Air

could pit 552 modern fighters—278 MS.406s, 98 Hawk 75s, 140 Bloch MB.151s and 152s and 36 Dewoitine D.520s. The French fighters (see

Table 5

), ably supported by RAF Hurricanes, fought back fiercely, but without an effective early warning system they were unable to bring sufficient force to bear.

The essence

of the Blitzkrieg

is speed. The two biggest natural obstacles to the advance of the

Wehrmacht

across Belgium were the Albert Canal and the River Maas (Meuse). Bridges over these had been captured on May 10; it was only to be expected that the Allies would make strenuous efforts to cut them. The air defence of the bridges was assigned to

JG 27

, a recently formed composite unit equipped with Bf 109Es. Operations during the previous two days had reduced its strength, but it still had about 85 fighters serviceable.

At dawn on 12 May, 7 and

2/JG

7, led by Spanish Civil War veteran Joachim Schlichting, intercepted a formation of nine RAF Blenheims over Maastricht and, in the ensuing battle, claimed six of them.

3/JG 1

, patrolling over Liége, encountered the survivors on their egress and accounted for two more. It was the pattern for the day. The small fighter escorts which were all the Allies could provide were brushed aside and the bombers were mercilessly hacked from the skies. During the course of the day

JG 27

mounted no fewer than 340 sorties, claiming 28 victories for the loss of four of its own aircraft.

Note:

Most of the

Geschwader

listed are composite units. This arose from the continued expansion of the fighter arm.

The day was notable for another reason. German veteran Adolf Galland had led a Heinkel He 51 unit in Spain, flying ground attack missions. In Poland he had then commanded

2

(

Schlacht)/LG 2

, equipped with Henschel Hs 123 biplanes, in the same role. But air combat had so far eluded him. At last his longed-for transfer to fighters had come through, and he became the operations staff officer of

JG 27,

flying Bf 109Es. May 12 1940 saw him freelancing near Liége in company with Gustav Rödel when he encountered eight Hurricanes about 3,000ft below. His combat report reads:

The enemy was attacked from a position of advantage above and astern. The first burst with machine guns and cannon hit the enemy aircraft. When I broke away Leutnant Rödel fired and scored hits. The enemy machine spiralled down and I followed, firing from a distance of between 50 and 70m. Parts of the aircraft were observed to break off and it spun down into the clouds. Ammunition used: 90 cannon shells; about 150 machine gun bullets. The Hurricanes appeared poorly trained and failed to support each other.

The records of fighter-versus-fighter combat in all eras show that in something like 80 per cent of all cases, the victim either never sees the one that gets him or only becomes aware of being under attack when his assailant has already reached a position of decisive advantage. Such was the case with Galland’s first victory. Two more Hurricanes fell to his guns that day: the man who many consider to have been the greatest fighter pilot of the war had opened his account.

The RAF quickly reinforced their four Hurricane squadrons with six more, and added two squadrons of Gloster Gladiator biplanes. However, it was now too late. Spearheaded by the

Luftwaffe

, the victorious

Wehrmacht

thrust past the end of the vaunted Maginot Line at Sedan and advanced rapidly across France towards the Channel ports, effectively severing the BEF and the northern Allied armies from the rest of France.

May 14 saw heavy fighting in the air as the French threw in everything they had to stop the German breakthrough at Sedan. Among the many German victories, Hans-Karl Mayer of

I/JG 53

claimed five on this day, while Werner Mölders of

III/JG 53

, who had ended the Spanish Civil War as top scorer with 14, shot down a Hurricane to bring his score in the French campaign to 11. By nightfall, the

Jagdflieger

had

flown 814 sorties over Sedan, and the remains of 89 Allied aircraft were counted on the ground in this sector.

As the aggressor, the

Luftwaffe

held the initiative, forcing the defenders to dance to their tune, and now this advantage was increased by an order of magnitude. As the speed of the German advance threatened to overrun the Allied airfields, the British and French air units were forced to retreat, often to emergency landing grounds with poor or nonexistent communications. The primitive French early warning system collapsed, spares, fuel and ammunition ran short and fighting effectiveness was greatly reduced. Morale was another factor with some French fighter units: as the French Army signally failed even to slow the German advance, so an atmosphere of defeatism spread. As Julius Neumann of

JG 27

once commented, he saw few French fighters during this period, and those he did see did not appear interested in engaging. This was not universal: the French fighter pilots had fought magnificently against overwhelming odds in the early stages, and many

Groupes

continued to do so to the bitter end. One of their victims was Hannes Gentzen, who went down on 26 May, having added 10 victories in France to his Polish tally of seven.

This period showed one significant trend. The Bf 110

Zerstörer

was even at this early stage found to be vulnerable in manoeuvre combat against the more agile Allied single-seaters and from May 1940 onwards started to adopt the defensive circle when attacked by fighters. In this, the rear of each aircraft is covered by the guns of the one behind it. The defensive circle was of course still vulnerable to attacks from the beam or above, but these involved shooting at high deflection angles. Few pilots could muster the necessary level of accuracy to succeed at this. On the other hand, the Bf 110 units usually operated in

Gruppe

or even

Geschwader

strength; if a single

Staffel

went into a defensive circle, other

Staffeln

were at hand to brush their assailants off their backs. There were never enough Allied fighters in the air to put a whole

Zerstörergeschwader

on the defensive, but, while it passed largely unremarked at the time, the writing was on the wall for the Bf 110.

Table 6. Sorties and Losses, Dunkirk, 27 May-2 June 1940

| | Sorties | Losses |

| Luftwaffe | | |

| Bf 109E | 1,595 | 29 |

| Bf 110C/D | 405 | 8 |

| Bombers (Do 17, He 111, Ju 88) | 1,010 | 45 |

| Dive bombers (Ju 87) | 805 | 10 |

| Totals | 3,815 | 92 |

| | | |

| Royal Air Force | | |

| Spitfire | 746 | 48 |

| Hurricane | 906 | 49 |

| Defiant/Blenheim | 112 | 9 |

| Totals | 1,764 | 106 |

The evacuation of the BEF and a fair portion of the French Northern Army from Dunkirk during late May and early June resulted in some of the hardest fighting the

Jagdflieger

had yet experienced. Even though many

Jagdgruppen

had moved forward into bases in Belgium and northern France, they were still operating at the limit of their effective range while simultaneously handicapped by a lack of fuel and spares, the supply organisation having failed to keep up with the advance.

The

Jagdflieger

encountered Spitfires for the first time during the Dunkirk evacuation. The performance of the British fighter was generally identical to that of the Bf 109E, while its manoeuvrability was rather better, which came as a nasty shock to the German pilots. But generally the

Jagdflieger

had a numerical advantage, operating in

Gruppe

strength whereas the British initially flew in squadrons of twelve aircraft. But, like the Germans, the British fighters were also operating at extreme range, which meant that it was a matter of chance whether they were both over the area at the same time.

Statistics appear to indicate that the

Jagdflieger

had rather the better of things: during the seven days of fighting they flew 2,000 sorties, losing 37 of their number, whereas British fighters flew 1,764 sorties, losing 106 (see

Table 6

). It should, however, be remembered that the main target for the British fighters was the German bombers and in attacking these they often became vulnerable to the prowling Messerschmitts.