Luftwaffe Fighter Aces (4 page)

Read Luftwaffe Fighter Aces Online

Authors: Mike Spick

The wider spacings adopted, about 1,800ft frontage for a

Schwarm,

made radical course changes a problem. Turning in the traditional manner caused the outside man to lag, even at full throttle, while the inside man was throttled back almost to the point of stall. Mölders solved this difficulty with the cross-over turn (

Fig. 6

). In this, the leader would call the turn and the outside man would immediately pull hard in the required direction, crossing above his comrades. After a short delay he would be followed by the next in line and so on, until all aircraft had turned on to the new heading, swapping sides in the formation as they went. This allowed very rapid changes of heading without the necessity to juggle the throttles, with each aircraft turning at its maximum. Wide spacings minimised the chance of mid-air collisions and allowed a lookout to be maintained throughout. Necessary changes in vertical separation could be made as the formation rolled out on the new heading.

Werner Mölders is often credited with inventing the cross-over turn, but in fact he did not. The origins of the manoeuvre are lost in the mists of time, but it seems probable that it was known to the Royal Air Force as early as 1918, and it was certainly shown in the first RAF Training Manual of 1922 as being used by a Vic of five aircraft. After this it seems to have fallen into disuse, probably due to the difficulty (and danger) of performing it in a multi-aircraft formation with perhaps less than 100ft spacing between them. Like many another good idea, its time had not yet come. It is probable that the wide lateral separation between aircraft introduced by

J 88

in the Spanish Civil War first made it a practical proposition.

The next tactical step corresponded to the cardinal principle of concentration of force. By this time there was no shortage of fighters, and it was often desirable to use the entire

Staffel

of twelve aircraft as a single unit. Formations adopted for this were three

Schwarme

either abreast or slightly sucked, stepped up away from the sun or stepped up in line astern. Standard attack tactics involved dive and zoom as initiated by the Soviet Republican units, as the Bf 109 was vulnerable in a turning fight against the agile Russian fighters.

Fig. 6.

Schwarm

Formation and Cross-over Turn

The typical

Schwarm

formation consisted of two elements of two with about 600ft spacings between aircraft. This allowed all pilots to keep a look-out without fear of collision. To turn through 90 degrees, the fighter on the outside pulled up and turned above the one nearest to it. The others followed in sequence, rolling out on to the new heading with formation integrity intact.

The involvement of the

Legion Kondor

in the Spanish Civil War allowed basic German fighter tactics to evolve to a stage where only minor adjustments were necessary in the world conflict to come. By contrast, the Allies were to learn many hard lessons before they finally caught up. A further advantage was that personnel were rotated through Spain at frequent intervals, which allowed a large pool of combat-experienced pilots to be formed within the

Luftwaffe.

This, however, poses the question: why did the Italians and Soviets not learn equally?

From the Italians’ viewpoint, their CR.32 fighters were outperformed by the Russian I-15s and I-16s. All too often, survival depended on the high agility of their Fiats, and they naturally came to look upon this as a cardinal virtue—an outlook easily adopted by such an aerobatically minded force. The Soviets did in fact learn much the same lessons as the Germans. It was they who had introduced dive and zoom tactics; they then copied the German pair and four as

the pary

and

zveno.

During 1938 they recommended this tactical system for adoption throughout the entire Soviet fighter force. That it was not put into effect was almost entirely due to Stalin’s maniacal purges, which swept away many veterans of Spain.

The Spanish Civil War ended in March 1939 when Republican resistance collapsed. The

Legion Kondor

was disbanded, and its members returned to their units. Having experience of actual aerial combat influenced fighter training considerably. Not only were the Spanish lessons readily absorbed: training was made more realistic. In the air forces of other nations, air combat training was generally a one-versus-one engagement, with both participants from the same unit and flying exactly the same type of aircraft. This reduced it to a contest of flying skill and experience. The

Jagdflieger

knew better. Much of their training consisted of multi-aircraft combats—four versus four, even at times

Staffel

versus

Staffel

—accepting the increased risk of mid-air collision. This served them well in years to come.

| I.THE LIGHTNING VICTORIES |

I have done my best, in the past few years, to make our

Luftwaffe

the largest and most powerful in the world. The creation of the Greater German Reich has been made possible largely by the strength and constant readiness of the Air Force. Born in the spirit of the German airmen of the First World War, inspired by faith in our

Führer

and commander-in-chief, thus stands the

Luftwaffe

today, ready to carry out every command of the

Führer

with lightning speed and undreamed-of might.Herman Goering, August 1939

The years preceding the Second World War saw Germany invade both Austria and what was then Czechoslovakia. Both operations were successfully carried out without bloodshed. Now it was the turn of Poland. The Poles were expected to resist, but, since they were outnumbered and outclassed both in the air and on the ground, a German victory was just a question of time. What Hitler did not reckon with was that Britain and France would undertake to guarantee Poland’s sovereignty, and that war with these two great powers would become inevitable.

In the event, the Anglo-French guarantee proved worthless. With the

Luftwaffe

spearheading the attack, Poland was overrun in a matter of weeks, and the plan to provide military assistance in the shape of British and French squadrons could not be implemented in time. There followed the period of the ‘Phoney War’, which was broken in the spring of 1940 when, in a dazzling series of operations, the

Wehrmacht

invaded and overran Denmark, Norway, Holland, Belgium and France in quick succession. In every case the

Jagdflieger

played a decisive role, sweeping the skies clear of enemy fighters to allow their bombers to operate with minimal interference, while inflicting devastating losses on Allied bomber formations when they tried to intervene in land operations.

Germany invaded Poland on the morning of 1 September 1939, opening an unbroken period of nearly six years during which the skies of Europe were never quiet. The operation was carefully planned in advance. The Polish Air Force was to be eliminated on the ground by a series of attacks on its airfields, leaving the way clear for the

Luftwaffe

attack and bomber units to support the ground troops.

It did not work out quite that way. The preceding period of international tension allowed the Poles to disperse their front-line aircraft to temporary strips. Then, in the event, early morning fog disrupted the German plan completely. The airfield assault, when it finally came, fell only upon obsolete and unserviceable combat aircraft and trainers. However, even with this initial setback, the odds were heavily in favour of the

Luftwaffe.

Not only did they have a sizeable numerical advantage: their aircraft were qualitatively far superior to those of the Poles, while their fighter tactics and training were, thanks to the Spanish experience, ahead of those of any other nation in the world.

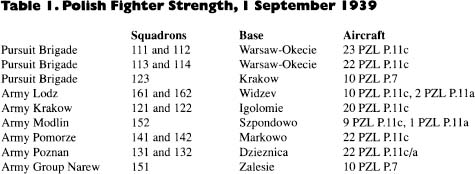

The Polish Air Force had been reorganised shortly before the war. On 1 September 1939 the fighter force consisted of a mere 161 aircraft, of which 30 were the obsolete PZL P.7, defending a frontage of approximately 350 miles. To make matters worse, centralised control was lacking. A relatively strong Pursuit Brigade of four squadrons and 45 fighters was based on Warsaw, plus a single understrength squadron far to the south at Krakow with ten obsolete fighters. The remainder were scattered around the various Polish army regions for air defence and bomber escort duties. See

Table 1

.

This mere handful of fighters, obsolete by the standards of the day, operating from makeshift airfields and using tactics which had remained unchanged since 1917, faced the might of the

Luftwaffe.

It was backed by a primitive early warning system based on ground observers linked by a rather fragile communications network. Once the shooting started, all semblance of centralised control was lost. Ranged against them were

Luftflotten 1

and

4

—about 1,500 aircraft in all. The sharp end consisted of 648 level bombers, 219 dive bombers, 30 attack

(Schlacht)

aircraft and 217 single- and twin-engine fighters. To the small and scattered Polish fighter arm, the odds were overwhelming.

The destruction of German records at the end of the war makes it difficult to establish exactly which fighter units took part in the Polish campaign. However, those known to have participated are detailed in

Table 2

.

Qualitatively, the disparity between the Polish fighters and those of the

Luftwaffe

was great. Both the P.7 and P. 11 were monoplanes, with high-set gull wings, fixed landing gear and open cockpits. The P.7 first flew in October 1930, and, powered by a Skoda-built Bristol Jupiter radial engine, could just about exceed 200mph in level flight at 10,000ft. Its rate of climb was 2,047ft/min and wing loading just under 171b/sq ft. Its armament was minimal—two 7.92mm Vickers E machine guns. The P. 11 was basically a heavily modified P.7 adapted to take the much more powerful Bristol Mercury radial. The first prototype flew in August 1931 and the major variant in Polish service, the P.11c, could make 242mph at 18,045ft. Weight had inevitably increased, with wing loading rising to 20.51b/sq ft. The initial climb rate was 20 per cent better at

2,440ft/min, and armament consisted of two KM Wz.33 7.7mm machine guns. It was planned to fit a further pair of machine guns in the wings, but at the outbreak of war only about one third of all P.11s had been so adapted. Radio was another shortcoming: provision for its installation had been made, but it was not fitted to many aircraft.