Luftwaffe Fighter Aces (2 page)

Read Luftwaffe Fighter Aces Online

Authors: Mike Spick

I am therefore indebted to my friends Alfred Price and Edward Sims for permission to quote extracts from their published works, and to Martin Middlebrook for permission to use two passages from his book

The Nuremberg Raid.

All sources used are listed in the Bibliography. My thanks are also due to my friends at Cranwell College Library and

the Royal Aeronautical Society, and to Mr Brian Cocks of Helpston, for their generous help in making information available.

The German fighter arm did not use the expression ‘ace’, preferring ‘

Experte

’

.

This expression I have used throughout. Nor have I anglicised the spelling of German names except for the few cases where this is already widely accepted.

Geschwader, Gruppe

and

Staffel

have been left in their original forms, as English approximations are misleading. Ranks have for the most part been omitted: rapid promotion is a feature of war, and to go from corporal to colonel in the space of a paragraph or two is not only confusing but unnecessary. Finally, I have used the widely accepted ‘Bf’ (Bayerische Flugzeugwerke) for early Messerschmitt fighters, changing to ‘Me’ where the Germans themselves did so.

Mike Spick

I had seen Tempests above me, I could see them beside me, and new Tempests were approaching from underneath. My only chance lay in evading them until I could reach the cloud layer. So I tore off at top speed towards the cloud, jinking to the left and right with the rudder. This deceived the enemy behind me as to my direction of flight, and the more rapidly I trod on the rudder pedal the more difficult it was for the reflex sights behind me to show the right deflection. As a result, the fire of the Tempests missed to the side, since the pilots relied on the views in their sights. The trick worked well. I reached the cloud and attempted a zoom climb, intending to come around into a head-on firing pass at the Tempests, breaking up their attack. This was not to happen, since a Tempest below me could see me in the thin cloud and reported my direction of flight to my pursuers. Thus a Tempest was waiting to attack me when I left the cloud, and struck my wounded bird in the tail area. After a sharp blow, which I could feel through the control stick, my elevators failed. It was time to get out.

I jettisoned the canopy at about 600km/hr, released my harness, and was sucked from the cockpit of my FW, which was now standing on its nose. I was hurled upside down along the fuselage, and the fin struck my left arm so hard that it broke it, ripping the sleeve from my leather jacket.

The fate of FW 190D pilot

Unteroffizier

Georg Genth of

12/JG 26

represents in miniature that of the

Luftwaffe

fighter arm itself, the once-proud

Jagdflieger.

Heavily outnumbered, and for the most part with their aircraft outclassed, they were hunted down and shot from the skies over their own homeland. Genth survived this encounter, which took place on 7 March 1945, with injuries that were relatively minor but which were still enough to put him out of the war. Over the previous six years, tens of thousands of his comrades had not been so lucky. Although the cause for which they had fought was tarnished, their honour was redeemed by the lustre of their deeds.

When the skies over Europe were finally still and the victorious Allies had overrun the Third Reich on the ground, the record of the

Jagdflieger

became available for inspection. It caused a sensation. The scores of the German fighter pilots totally eclipsed those of their Allied counterparts. Whereas a tally of 30 victories was exceptional among British and American fighter pilots, a mere 35 German pilots were credited with the destruction of no fewer than 6,848 aircraft in air combat—an average of almost 196! Two of them had actually topped the 300 mark! Even in the demanding scenario of night fighting, two pilots had recorded over 100 victories.

These figures were at first regarded with incredulity by the Allies: the Nazi propaganda department headed by Dr Joseph Goebbels had long made all German pronouncements suspect. Then, as serious researchers investigated, it was found that while overclaiming is and always has been a feature of air warfare, regardless of period and nationality, the claims of the

Jagdflieger

had been made in good faith, and had been examined as rigorously as circumstances permitted before confirmation was issued.

The fighter ace needs a unique combination of gifts to succeed. Physically he needs to be fit, and to have first class vision, with a bias towards long-sightedness. He must be a good shot, with a flair for deflection shooting at fast-moving targets. His physical reactions must be fast and instinctive, as in fighter combat there is little time for reasoned action. He must be an accomplished aircraft handler, without necessarily being proficient in aerobatics—the latter merely serve to give confidence, and to allow the pilot to get used to functioning in unusual attitudes.

Courage is a term widely applied to fighter pilots, but self-control is a far more appropriate one. In war, the pilot functions under the threat of imminent extinction or maiming. One of the more usual ways for him to depart this vale of tears is in flames, trapped in the cockpit. Wounds are hardly better: there is no one to give immediate aid, and he is entirely dependent upon his own resources. Truly, no warrior is more alone than the pilot of a single-seat fighter. Fear must be channelled into action if he is to survive, let alone overcome the enemy, and this calls for the ultimate in self-control.

Aggression is essential, although it must be tempered with caution. The ‘fangs out, hair on fire’ type rarely lasts long. In the confusion of a dogfight, it is all too easy to be lured into an irrecoverable situation, usually through target fixation at the expense of keeping a good lookout. As we shall see in a later chapter, Erich Hartmann, the ace of aces, was a very cagey individual in his methods and attitudes.

Finally there is the ability to survive. A really impressive score cannot be amassed overnight. It is therefore necessary to survive for long enough to make this possible. At first sight survival appears to be due to nothing more than luck. There is of course no doubt that luck—chance … call it what you will—plays a part in war. But there is more to it than that. Survival in air combat is largely dependent on a quality called situational awareness, or SA. This is basically the ability to keep track of events in a fast-moving, highly dynamic, three-dimensional situation, but there is a body of evidence to suggest that some sort of sixth sense is at work which warns a pilot of impending danger. It is unquantifiable, and it seems to work better on some days than others, but potentially SA is the fighter pilot’s greatest asset.

By a convention established in the First World War, a fighter pilot with five confirmed victories becomes an ace. This standard was adopted by most combatants, although Germany was out of step in settling for ten! In the Second World War the same convention was applied by the Allies, whereas Germany dropped the expression altogether in favour of the term ‘

Experte

’

.

To be regarded as such, a fighter pilot had to demonstrate his proficiency in combat rather than attain a set number of victories. By the five-victory convention, the

Luftwaffe

produced something like 2,500 aces in all; the number of

Experten

was far smaller.

The Ritterkreuz

(Knight’s Cross) was awarded to just over 500 German fighter pilots.

Another area in which the

Luftwaffe

differed from the Allies was in the use of a points system for decorations, although this only applied from about 1943 for operations against the West. Half a point was awarded for the destruction of an already damaged twin-engine aircraft and one point for destroying a single-engine aircraft, damaging a twin-engine type or the final destruction of a four-engine bomber; two points were awarded for destroying a twin-engine aircraft or damaging a multiengine

bomber sufficiently to separate it from its formation; and three points were awarded for a multi-engine bomber brought down. As we shall see later, the latter was an extremely difficult feat to accomplish.

From about 1943, the unprecedentedly high scores of the

Experten

resulted in a certain amount of standardisation for decorations. On the Russian Front, the

Ritterkreuz

was awarded after 75 victories, with the

Eichenlaub

(Oak Leaves) to the

Ritterkreuz

due between 100 and 120 victories, the

Eichenlaub mit Schwerten

(Oak Leaves with Swords, irreverently known as the ‘cabbages, knives and forks’) at 200 and finally the

Eichenlaub mit Schwerten und Brilliante

(Diamonds) above 250.

In the West, with the points system operating, a pilot could earn the

Ritterkreuz

with between 40 and 50 points; therefore fifteen heavy bombers, or between 40 and 50 fighters in the West, were equal to 75 Soviet aircraft—which were for the most part single-engine—in the East.

If we accept the enormous scores of the

Experten

as at least being in the right area, other questions spring to mind. Was their equipment in any way superior to that of the Allies? Were they better trained? Were their tactics better? To answer these, at least partially, we should start with a look at how the

Luftwaffe

itself came into existence.

Luftwaffe

Following the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, military aviation was forbidden in Germany, as was the construction of any type of aircraft. The latter restriction was lifted in 1922, allowing the production of small civil machines. This in effect kept the German aviation industry in being—a factor that was to have far-reaching consequences.

Even in defeat, Germany was an air-minded nation. During the Great War the German fighter aces—Boelcke, Richthofen, Udet and many others—had been household names. They became role models for the next generation. In 1920, the

Deutscher Luftsportsverband

was formed at the instigation of the Defence Ministry to encourage the population, and youth in particular, to take to the air. Mostly equipped with gliders, this organisation had a membership of 50,000 by 1929—far more than in other countries, in which aviation of any sort was generally the exclusive preserve of the wealthy. With free or subsidised flying and gliding

available, German youth became far more air-minded than that of other countries, providing a large pool of applicants with basic flying skills which could be drawn on when the time for expansion came.

In 1924,

General

Hans von Seekt moved one of his

Reichswehr

protégés into the Ministry of Transport as head of the Civil Aviation Department. Ernst Brandenberg was a former commander of the

England Geschwader

, and his appointment meant that the development of German civil aviation was henceforth conducted with future military needs in mind.

Shortly afterwards, a secret treaty with the Soviet Union allowed the establishment of a clandestine military aviation training school at Lipetsk, some 230 miles south of Moscow. Equipped with unmarked Fokker D.XIIIs, German pilots once more trained for war. It was also in the closed area at Lipetsk that new German combat aircraft underwent weapons trials. A further development was the formation of the state airline

Deutsche Lufthansa

in 1926. This had four flying schools, and, while ostensibly training civil airline pilots, it also formed a covert nucleus of military flyers.

When, in January 1933, Adolf Hitler became Chancellor, the pace was stepped up. One of his first appointments was that of Hermann Goering as

Reichskommissar

for Air. Goering, a First World War fighter ace with 22 victories and the final commander of the

Richthofen Geschwader,

was a charismatic figure guaranteed to catch the imagination of the masses. Although in those days a man of formidable energy and ability, he had many other duties, and the task of building the new

Luftwaffe

fell to his deputy Erhard Milch, a former fighter pilot and previously chairman of

Lufthansa,

One of Milch’s first tasks was to increase Germany’s aircraft production capability. With ample funds available, he did this by the simple expedient of placing large orders with several companies, on the strength of which they could build and equip new factories. Some idea of his success can be gauged from the fact that monthly aircraft output in 1933 was a mere 31, but by 1935 had risen by 854 per cent to 265! Priority was given to the development of new military aircraft types, to the construction of new airfields and to the establishment of more flying training schools.

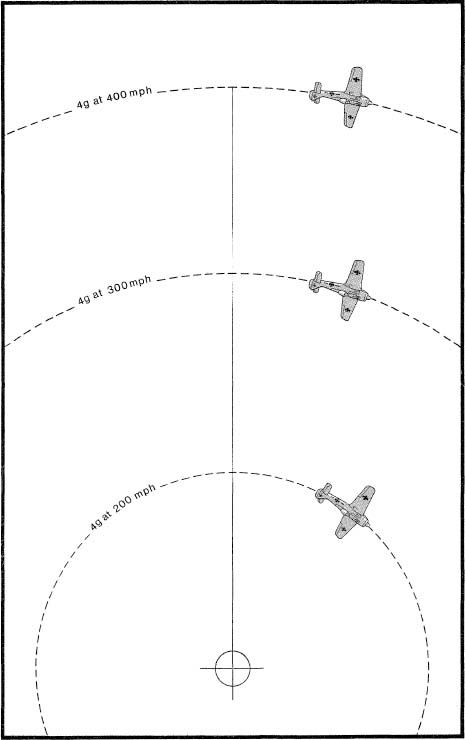

Fig. 1. Effect of Speed on Turn Radius

Speed reduces turning ability markedly. Depicted here to scale are the turn radii for the same fighter at three different speeds. Naturally, this influenced a pilot’s options in the dogfight.

This huge expansion could scarcely go unremarked abroad, and in March 1935 the existence of the new

Luftwaffe

was formally revealed. At its inception, its strength was 20,000 personnel and no fewer than 1,888 aircraft. In September of that same year, the first flight took place of a radically new fighter, the Messerschmitt Bf 109. Eventually built in greater numbers than any other fighter, the Bf 109 was a cantilever construction monoplane with an enclosed cockpit, retractable main gear and automatic slots on the wing leading edge. At that time it represented the cutting edge of technology. The same period also saw the emergence of several other types of advanced military aircraft, among them the Bf 110 heavy fighter and the Junkers Ju 88 fast bomber. The expansion of the

Luftwaffe,

coupled with the development of advanced warplanes which were equal to anything produced anywhere in the world, in such a short space of time, was an achievement of no mean order.