Junk DNA: A Journey Through the Dark Matter of the Genome (4 page)

Read Junk DNA: A Journey Through the Dark Matter of the Genome Online

Authors: Nessa Carey

The function of the Fragile X protein is to carry lots of different RNA molecules around in the cell. This gets them to the correct locations, influences how these RNAs are processed and how they generate proteins. If there is no Fragile X protein, the other RNA molecules aren’t properly regulated, and this plays havoc with the normal functioning of the cell.

8

For reasons that aren’t clear, the neurons in the brain seem particularly sensitive to this effect, hence the learning disability in this disorder.

An everyday analogy may help with visualising this. In the UK, a relatively small amount of snow can incapacitate the transport networks. The snow covers the roads and the railway tracks, preventing cars and trains from moving. When this happens, people can’t get to their place of work and this creates all sorts of problems. Schools can’t open, deliveries aren’t made, banks can’t dispense cash, etc. One starting event – the snow – has all sorts of consequences because it ruins the transport systems in society. A similar thing happens in Fragile X syndrome. Just like snow on the roads and railway tracks, the effect of the mutation is to mess up a transport system in the cell, with multiple knock-on effects.

Switching off the expression of a specific gene is the key step in the pathology of both Friedreich’s ataxia and Fragile X syndrome. Support for this hypothesis has been provided by very rare cases of both disorders. There are small numbers of patients where the repeat in the junk regions is of the same small size found in most healthy people. In these patients, there are mutations that change the sequence in the amino acid-coding regions. These particular amino acid sequence changes actually make it impossible for the cell to produce the protein. In other words, it doesn’t matter why the protein isn’t expressed. If it’s not expressed, the patients have the symptoms.

Just when you have a nice theory

So far it might seem like there’s a nice straightforward theme emerging. We could speculate that expansions in the junk regions are only important because they create abnormal DNA. This DNA isn’t handled properly by the cells, resulting in a lack of specific important proteins. We could suggest that normally these junk regions are unimportant, with no significant role in the cell.

But there is something that argues against this. The normal range of repeats in both the Fragile X and Friedreich’s ataxia genes is found in all human populations, and has been retained throughout human evolution. If these regions were completely nonsensical we would expect them to have changed randomly over time, but they haven’t. This suggests that the normal repeats have some function.

But the real grit in this genetic oyster comes from myotonic dystrophy, the disorder that opened Chapter 1. The myotonic dystrophy expansion gets bigger as it passes down the generations. A parent’s chromosome may contain the sequence CTG repeated 100 times, one after another. But when they pass this on to their child, this may have expanded so the child’s chromosome has the sequence CTG repeated 500 times. As the number of CTG repeats gets larger, the disease becomes more and more severe. This isn’t what we would expect if the expansion just switches off the nearby gene. All cells of someone with myotonic dystrophy contain two copies of the gene. One carries the normal number of repeats, and the other carries the expanded number. So, one copy of the gene should always be producing the normal amount of protein. That would mean that the most the overall levels of the protein should drop would be about 50 per cent.

We could hypothesise that as the repeat gets longer there is progressively less gene expression from the mutant version of the gene. This could lead to a gradual decline in the amount of protein produced overall. This could range from a 1 per cent drop overall

for fairly small expansions, to a 50 per cent final decrease for the large ones. This could lead to different symptoms. The problem is that there aren’t really any inherited genetic diseases like this. We just don’t see disorders where very minor variations in expression have such a big effect (all patients with the expansion develop symptoms), but with such fine tuning between patients (the symptoms becoming more extreme as the expansion lengthens).

It’s worth looking at where the expansion occurs in the myotonic dystrophy gene. It’s right at the far end, after the last amino acid-coding region. In Figure 2.5, this would be on the horizontal line to the right of box ‘G’. This means that the entire amino acid-coding region can be copied into RNA before the copying machinery encounters the expansion.

It’s now clear that the expansion itself gets copied into RNA. It is even retained when the long RNA is processed to form the messenger RNA. The myotonic dystrophy messenger RNA does something unusual. It binds lots of protein molecules that are present in the cell. The bigger the expansion, the more protein molecules that get bound. The mutant myotonic dystrophy messenger RNA acts like a kind of sponge, mopping up more and more of these proteins. The proteins that bind to the expansion in the myotonic dystrophy messenger RNA are normally involved in regulating lots of other messenger RNA molecules. They influence how well messenger RNA molecules are transported in the cell, how long the messenger RNA molecules survive in the cell and how efficiently they encode proteins. But if all these regulators are mopped up by the expansion in the myotonic dystrophy gene messenger RNA, they aren’t available to do their normal job.

9

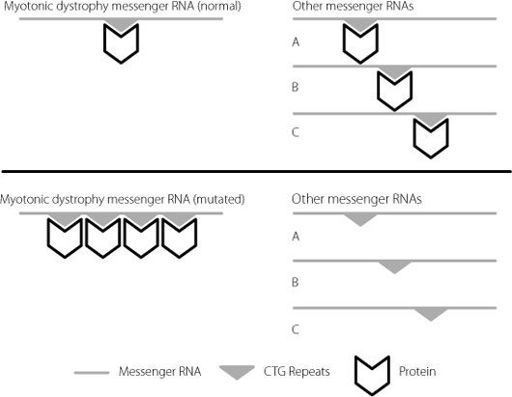

This is shown in Figure 2.6.

Again an analogy may help. Imagine a city where every member of the police force is engaged in controlling a riot in a single location. There will be no officers left for normal policing, and burglars and car thieves may run amok elsewhere in the city. It’s the

same principle in the cells of people with the myotonic dystrophy mutation. The CTG repeat sequence expansion in a single gene – the myotonic dystrophy gene – ultimately leads to mis-regulation of a whole number of other genes in the cell.

Figure 2.6

The upper panel shows the normal situation. Specific proteins, represented by the chevron, bind to the CTG repeat region on the myotonic dystrophy messenger RNA. There are plenty of these protein molecules available to bind to other messenger RNAs to regulate them. In the lower panel, the CTG sequence is repeated many times on the mutated myotonic dystrophy messenger RNA. This mops up the specific proteins, and there aren’t enough left to regulate other messenger RNAs. For clarity, only a small number of repeats have been represented. In severely affected patients, they may number in the thousands.

This is because the expansion mops up more and more of the binding proteins as it gets larger. This leads to disruption of a greater quantity of other messenger RNAs, causing problems for increasing numbers of cellular functions. This eventually results in

the wide range of symptoms found in patients carrying the myotonic dystrophy mutation, and explains why the patients with the largest repeats have the most severe clinical problems.

Just as we saw in Friedreich’s ataxia and Fragile X syndrome, the normal CTG repeat sequences in the myotonic dystrophy gene have been highly conserved in human evolution. This is consistent with them having a healthy and important functional role. We are even more convinced this is the case for the myotonic dystrophy gene because of the proteins that bind to the repeat in the messenger RNA. These also bind to shorter repeat lengths, of the size that are present in normal genes. They just don’t bind in the same abundance as they do when the repeat has expanded.

It’s clear from the myotonic dystrophy example that there is a reason why messenger RNA molecules contain regions that don’t code for proteins. These regions are critical for regulating how the messenger RNAs are used by the cells, and create yet another level of control, fine-tuning the amount of protein ultimately produced from a DNA gene template. But what no one appreciated when the myotonic dystrophy mutation was identified, almost ten years before the release of the human genome sequence, was just how extraordinarily complex and variable this fine-tuning would turn out to be.

3. Where Did All the Genes Go?

On 26 June 2000, it was announced that the initial draft of the sequence of the human genome had been completed. In February 2001, the first papers describing this draft sequence in detail were released. It was the culmination of years of work and technological breakthroughs, and more than a little rivalry. The National Institutes of Health in the USA and the Wellcome Trust in the UK had poured in the majority of the approximately $2.7 billion

1

required to fund the research. This was carried out by an international consortium, and the first batch of papers detailing the findings included over 2,500 authors from more than 20 laboratories worldwide. The bulk of the sequencing was carried out by five laboratories, four of them in the US and one in the UK. Simultaneously, a private company called Celera Genomics was attempting to sequence and commercialise the human genome. But by releasing their data on a daily basis as soon as it was generated, the publicly funded consortium was able to ensure that the sequence of the human genome entered the public domain.

2

An enormous hoopla accompanied the declaration that the draft human genome had been completed. Perhaps the most flamboyant statement was from US President Bill Clinton, who declared that ‘Today we are learning the language in which God created life’.

3

We can only speculate on the inner feelings of some of the scientists who had played such a major role in the project as a politician invoked a deity at the moment of technological triumph. Luckily, researchers tend to be a shy lot, especially when

confronted by celebrities and TV cameras, so few expressed any disquiet publicly.

Michael Dexter was the Director of the Wellcome Trust, which had poured enormous sums of money into the Human Genome Project. He was not much less fulsome, albeit somewhat less theistic, when he defined the completion of the draft sequence as ‘The outstanding achievement not only of our lifetime, but in terms of human history’.

4

You might not be alone in thinking that perhaps other discoveries have given the Human Genome Project a run for its money in terms of impact. Fire, the wheel, the number zero and the written alphabet spring to mind, and you probably have others on your own list. It could also be claimed that the human genome sequence has not yet delivered on some of the claims that were made about how quickly it would impact on human disease. For instance, David Sainsbury, the then UK Science Minister, stated that ‘We now have the possibility of achieving all we ever hoped for from medicine’.

5

Most scientists knew, however, that these claims should be taken with whole shovelfuls of salt, because we have been taught this by the history of genetics. Consider a couple of relatively well-known genetic diseases. Duchenne muscular dystrophy is a desperately sad disorder in which affected boys gradually lose muscle mass, degenerate physically, lose mobility and typically die in adolescence. Cystic fibrosis is a genetic condition in which the lungs can’t clear mucus, and the sufferers are prone to severe life-threatening infections. Although some cystic fibrosis patients now make it to the age of about 40, this is only with intensive physical therapy to clear their lungs every day, plus industrial levels of antibiotics.

The gene that is mutated in Duchenne muscular dystrophy was identified in 1987 and the one that is mutated in cystic fibrosis was identified in 1989. Despite the fact that mutations in these genes were shown to cause disease over a decade before the completion

of the human genome sequence, there are still no effective treatments for these diseases after 20-plus years of trying. Clearly, there’s going to be a long gap between knowing the sequence of the human genome, and developing life-saving treatments for common diseases. This is especially the case when diseases are caused by more than one gene, or by the interplay of one or more genes with the environment, which is the case for most illnesses.

But we shouldn’t be too harsh on the politicians we have quoted. Scientists themselves drove quite a lot of the hype. If you are requesting the better part of $3 billion of funding from your paymasters, you need to make a rather ambitious pitch. Knowing the human genome sequence is not really an end in itself, but that doesn’t make it unimportant as a scientific endeavour. It was essentially an infrastructure project, providing a dataset without which vast quantities of other questions could never be answered.

There is, of course, not just one human genome sequence. The sequence varies between individuals. In 2001, it cost just under $5,300 to sequence a million base pairs of DNA. By April 2013, this cost had dropped to six cents. This means that if you had wanted to have your own genome sequenced in 2001, it would have cost you just over $95 million. Today, you could generate the same sequence for just under $6,000,

6

and at least one company is claiming that the era of the $1,000 genome is here.

7

Because the cost of sequencing has decreased so dramatically, it’s now much easier for scientists to study the extent of variation between individual humans, which has led to a number of benefits. Researchers are now able to identify rare mutations that cause severe diseases but only occur in a small number of patients, often in genetically isolated populations such as the Amish communities in the United States.

8

It’s possible to sequence tumour cells from patients to identify mutations that are driving the progression of a cancer. In some cases, this results in patients receiving specific therapies that are tailored for their cancer.

9

Studies of human evolution and

human migration have been greatly enhanced by analysing DNA sequences.

10