Insectopedia (28 page)

It was the complexity of the bees’ behavior that was so arresting. Making connections between the intricate sociality of honeybees—which live in self-reproducing “colonies” of thousands of individuals—and the development of sophisticated forms of communication is commonplace now. But early-twentieth-century animal studies were dominated by the conviction of biologists and psychologists that animal behavior was fully explicable in terms of a range of simple stimulus responses, such as reflexes and tropisms. And von Frisch’s bees were doing something that leading behaviorists such as John B. Watson and Jacques Loeb considered impossible: they were communicating symbolically, representing information through a form—a predictable pattern of physical movements—that was tied to its object “by social convention, tacit agreement, or explicit code.”

15

What was more, this representing could take place several hours after the flight it described. It relied on registering the details of that flight, recalling its content, and, of course, translating and performing the significant information. Moreover, it also required an audience able to interact effectively in its interpretation. To Donald Griffin, the tireless advocate of animal consciousness and the sponsor of von Frisch’s 1949 lecture tour of the United States, this was “the most significant example of versatile communication known in any animal other than our own species.”

16

Von Frisch went further. It was, he believed, an accomplishment “without parallel elsewhere in the entire animal kingdom.”

17

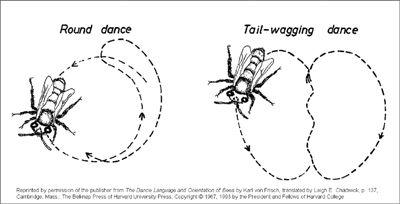

Contemporary bee researchers have refined von Frisch and Beutler’s wartime revisions of the dance theory. There is, most now believe, no difference between the types of information contained in the two main

dances.

18

Both use waggling to communicate distance and direction, and in both it is the enthusiasm of the performance that conveys the quality of food. Similarly, in both, the type of flower is revealed by the scent clinging to the insect’s body.

In Munich, von Frisch had placed feeding stations directly alongside the hive to facilitate communication between his assistants observing the dances and those stationed at the feeders. However, in the round dances that the bees perform to indicate nearby food, the waggles are abbreviated, occurring just as the dancer turns to begin her new circle. Von Frisch and his team failed to observe those subtle cues, and it is likely that the bee audience doesn’t take much notice of them either, relying instead on sense of smell to locate such proximate feeding places. But when food is further away—the transition occurs at a point between 50 and 100 yards for the Carniolan bee, the bee favored by von Frisch—bees returning to the hive interpose an additional sequence of steps, a straight run that contains a “vigorous wagging” of the abdomen, a side-to-side movement they may repeat thirteen to fifteen times per second.

19

It is this distinctive stretch that contains the critical information. Gyrating in darkness amid the crush of bodies on what von Frisch called the hive’s “dance floor,” the returning forager is closely shadowed by three or four followers, who receive the dance information with their antennae, utilizing scent (to identify the type of flower), taste (to gauge the quality of its product), touch, and an acoustic sensitivity that allows them to pick up the near-air movements produced by the dancer’s wings.

20

The dancer uses the sun as her reference point. Illuminated by daylight on the horizontal platform at the hive entrance, her movements are

indexical, pointing directly ahead, “just as we point to a distant goal with raised arm and outstretched finger.”

21

Dancing in the open, she orients herself by angling her body so that the sun is at the same angle relative to her body as it was during her recent flight to the food source.

22

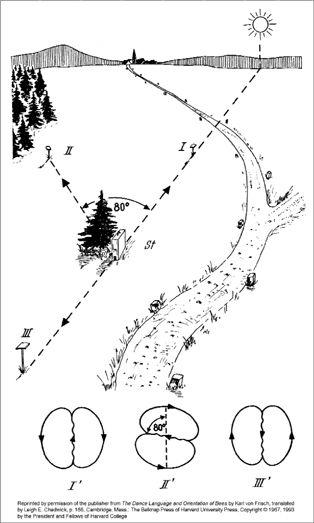

But the vast majority of dances take place inside the hive, in total darkness, on the surface of a vertical comb. Those conditions present the bee with a significant set of problems, which she resolves by reconfiguring the indexical association between the dance and the food source. This interior dance involves a temporal and spatial displacement as the bee converts the angle of the sun, which has permitted her to mime her flight during the outdoor dances, into gravitational terms. To succeed, the bee must note optically the angle between the direction of the sun and the food source on her outbound flight, remember that information, accurately transpose it to an angle that relates to gravity, and in doing so, include a calculation that corrects for the movement of the sun in the time that has passed between her outbound flight and the dance.

23

If food is located in the direction of the sun, the bee runs upward along the comb; if the feeding place is away from the sun, she runs down. If the material is located at, say, eighty degrees to the left of the sun—as in feeding table II in the diagram—she points her waggle run eighty degrees to the left of vertical (II’), and so on.

24

Even if the sun is obscured by clouds, she can locate its position by recognizing patterns of polarized light invisible to humans.

25

Von Frisch tracked bees foraging some seven miles from their hive and discovered that they convey distance through some combination of number and rate of waggles, velocity of forward movement, and length and duration of the straight section.

26

However, distance is a “subjective” quality, which bees measure in terms of the amount of effort they expend on their outward flight. Von Frisch demonstrated this by appending weights of different kinds to various parts of the animals’ bodies, exposing them to head winds, and forcing them to walk. In each case, they reported a greater distance than they did without the handicap.

27

Von Frisch liked to work with “calm and peaceful” bees.

28

They were cooperative, and he was responsive, designing experiments and apparatus around their needs and desires. The bees were affected by wind and temperature. They revealed astonishingly subtle senses of smell and

touch. They responded actively to changing light conditions. They grew to recognize individual field-workers. Alert to their sensitivities, he could never be certain that their observed behavior was not symptomatic of the artificiality of experimental conditions and so allowed them to force him into exhaustive (and exhausting) replications of his tests as he struggled to find ways to repeat controlled experiments in natural conditions. When his discoveries were too astonishing, he wondered whether his attention had created “a sort of scientific bee.”

29

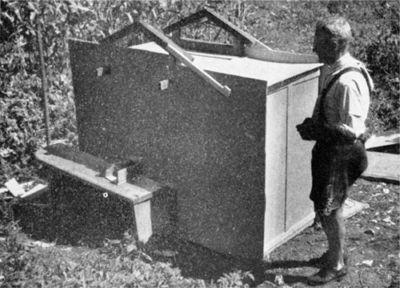

He began by building an observation hive. This was a standard beekeeping hive fitted with glass windows, through which the bees could be

watched relatively undisturbed. But he soon realized that bright sunlight and the visibility of patches of sky distorted the dances, so instead he developed his own range of hives with removable panels that allowed him to manipulate external conditions.

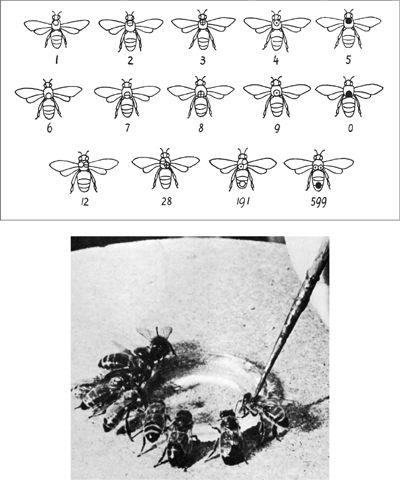

He designed feeding stations and special food dispensers. And he invented an automatic counting apparatus disguised as a flower to record bee visits when it was impractical or unnecessary to use volunteers.

He devised a coding scheme—an ingenious one—that allowed visual identification of hundreds of individuals. And he used a fine brush to number each bee with spots of colored lacquer while they fed from his sugar water.

But his true gift was in the design of simple and effective experiments of exceptional elegance. (He initially translated the dance language, for example, by systematically removing to progressively greater distances from the hive the food source that his bees had been trained to seek and then closely observing the dances performed by the returning foragers.) And what underlay this—in addition to patience, self-criticism, and a creatively methodical practice—was his natural historical eye for bee ecology, temperament, and habit, and a deep affinity with bee ontology, the being of a bee.