Insectopedia (29 page)

It was all this that enabled him to recognize the individuality of the

members of the hive, their characteristic predilections and temperaments, their shifting moods, and their subtle variations of activity. It was, without doubt, a profoundly anthropomorphic commitment. His bees are “shrewd,” “eager,” and “phlegmatic”; at one point they even exhibit “class consciousness.”

30

But it would be a mistake to think that anthropomorphism, which we could think of here as the impulse to understand other beings by reference to human interiority, is a sufficient framework through which to make sense of his work. For von Frisch, the honeybees were personal friends, but they were also profoundly mysterious in their difference. And it is this gap and its crossings that permit both reverence and subjection, both the relentless search for some kind of redemptive communion and the willingness to brutalize along the way.

Perhaps it is just the moment in which all this is taking place (the terrifying, dehumanizing political-historical moment that is also the thrilling moment in which all these discoveries are entirely new). Or perhaps it is the revived ethological determination to find the human in the animal. But it is clear that both in von Frisch’s estimation and in the unfolding of his study, the bees were his collaborators as much as his subjects. He tests them—and makes no effort to hide his disappointment on the rare occasions when they fail to demonstrate their acuity. But they also test him: challenging him to devise experiments sufficiently

sensitive to approximate their enigmatic way of being.

Von Frisch plunged into the Brunnwinkl research as into the lustrous depths of another world. “I tried to bury myself in it completely,” he recalled, “taking as little notice as I could help of the events around me.” Life outside Brunnwinkl was beyond control. In Munich, the Institute of Zoology lay in rubble, his house, too, “a gaping hole.” The hostilities of professional life confounded him. He persuaded his wife to burn her diary.

31

Who could be trusted? Who was reading? Who might be listening? But the bees … The bees spoke, but they were indifferent to politics. Theirs was a language unsullied by the corrupting jargon of the Third Reich. The bees had a purity. The bees had an intelligible rationality. The bees offered refuge.

We don’t know how Ruth Beutler felt, but Martin Lindauer, eventually von Frisch’s most distinguished student, describes returning severely wounded to Munich from the Russian front, expressing the desire to study science, and being sent by his doctor to attend a lecture on cell division by Karl von Frisch. Lindauer recalls the event as an epiphany that opened the prospect of a normal, meaningful life for a confused twenty-one-year-old who had refused to join the Hitler Youth and had been sent instead to dig the foundations of Dachau, who had volunteered for the German army after an earlier lecture—this by SS officers recruiting at his high school—and who found in von Frisch a stern mentor with a “zeal for science … [who] tolerated no fraud … [who was] an extremely exacting person.”

32

Perhaps it’s no surprise that, like his teacher, Lindauer experienced a profound attachment to the bees. As the national authoritarian order descended into chaos and conditions for professional science crumbled all around, von Frisch created an island of calm on Lake Wolfgang, finding in his honeybees a regularity, an ordered way of being in which, as in all well-run institutions, none need fear the unpredictable, none need feel unmoored. It was again the Germany of the amateur museum beside the Austrian lake, the Germany before the 1918 revolution, before the Weimar inflation, before the irruption of the Nazis. “After experiencing the senseless regime of the Hitler time, which was malicious, dishonest, and wrong from all perspectives,” Lindauer told an interviewer half a century later, “I drew strength from having work based on absolute correctness, honesty, and objectivity. Out of this material and

spiritual collapse, this hopelessness, I was able, with Karl von Frisch as a teacher, to build a new way of life. I found a new home with the bees. It was really a new home, the bee colony.”

33

It is not hard to understand. The honeybee colony has tens of thousands of members whose everyday life is a wonder of self-regulated complexity, a productive order continuously brought into being through the intricate fluidity of its social relations, exchange practices, and division of labor. The very first thing von Frisch tells us in his 1953 work

The Dancing Bees

is that honeybees are obligate social beings, that the level of task integration and cooperative interdependence is such that a bee alone cannot survive outside the hive: “There is no smaller unit [than the colony].… One single bee, kept all by itself, would soon perish.”

34

Like ants, termites, and the other social insects, honeybees live in what entomologists call caste societies, an analogy zoologists use to indicate the presence of morphologically distinct occupational groups: the egg-laying queen, the multitude of nonreproductive female workers, and the few hundred fat male drones with big eyes whose sole purpose—so far as we know—is to have sex with the queen on her single mating flight and who ultimately, as winter approaches and food resources dwindle, will be dragged from the hive by the workers, expelled to starve or, if resistant, stung to their death. “From that time onwards until the following spring,” wrote von Frisch, evoking the feminist utopias of writers such as Charlotte Perkins Gilman, “the females of the colony, left to

themselves, keep an undisturbed peace.”

35

Not surprisingly, it was the workers that attracted the researchers’ attention. Von Frisch and Beutler catalogued their dances, and they made far-reaching discoveries concerning their orientation abilities. Lindauer extended their findings to swarming, nest location, and the extraordinary process of nest selection, which I describe below. All three carried out detailed studies of workers’ division of labor and time allocation, although Lindauer pushed this furthest, by tracking the entire life history of a bee he called 107.

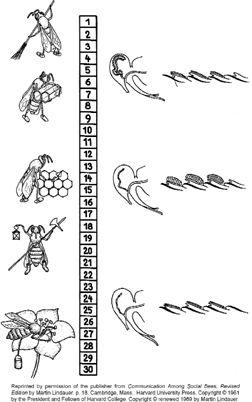

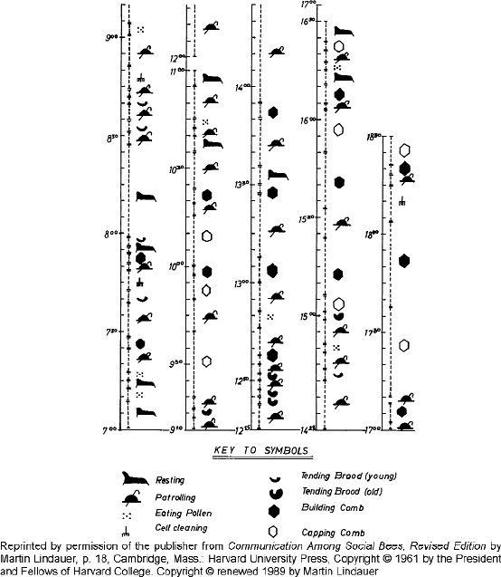

Below is Lindauer’s first schematic of worker labor allocation. It shows what Thomas Seeley has called a “division of labor based on temporary specializations” and comes from Lindauer’s classic 1961 account,

Communication among Social Bees

, a collection of lectures he gave at universities in the United States.

36

The column of figures indicates age in days. The whimsical bee people on the left are carrying out the activity

associated with a particular point in a bee’s life (cell cleaning, caring for the brood, building and repairing the hive, guarding the nest, foraging for nectar, pollen, and water). The sketches on the right show the corresponding development of glands in the animal’s head (the nurse, or feeding, gland) and abdomen (the wax glands). Despite this tight linkage of activity, physiology, and life cycle, Lindauer was fully aware that under critical circumstances—for example, a sudden food shortage—these relationships could be radically interrupted. In such a situation, the glands might stop developing and the bee begin foraging before its appointed day. A bee’s physiology and behavior were flexible, adaptive, and responsive to changing conditions.

But that isn’t all. When Lindauer tracked 107, he realized that she was not only spending more of her time multitasking than attending to the one expected assignment, but she was also doing an awful lot of wandering around (“patrolling,” indicated in Lindauer’s diagram by the bowler hat and walking stick) and a considerable amount of what appeared to be nothing (40 percent of her time, in fact, “resting” on the chaise longue). Lindauer found explanations for these observations. Patrolling, he reasoned, was a form of site monitoring that allowed the bee to identify immediate needs and allocate her time accordingly. “Loafing,” he claimed somewhat less convincingly, maintained the “reserve troops,” who could swing into action as occasion demanded.

37

Both of these unexpected activities suggested the importance of horizontal, peer-to-peer communication in a society organized without leaders or centralized decision making. The honeybees’ ability to maintain the hive’s internal environment—despite changes in external ambient conditions and the availability of critical resources—relies on contact between returning foragers and those already inside. The alacrity with which foragers are relieved of their loads, for instance, shows the degree of collective need for the substance in question. And not only is the recognizably sign-based language identified by von Frisch involved. Something more fundamental to social life is also going on. The bees are in constant physical contact, palpating each other’s head and antennae, sensing each other’s odor, passing compressed pollen to each other, sharing and exchanging the sugary contents of each other’s stomach, receiving each other’s near-field vibrations. Together, constantly, in the

deep communal darkness, exchanging substances, sucking and regurgitating, touching, feeling, smelling, tasting, sensing. Together, touching, in the warm darkness, sucking, feeling, touching, smelling, tasting, touching. Another country. Another language of bees.

And this language is somehow tied to that other language that is all around us here: the language of colonies, of castes and races, of sisters and half sisters, of queens and workers, the language of dance. The language of language, for heaven’s sake! This language didn’t disappear with von Frisch and Lindauer either. Today’s bee scientists speak it too, even if they often bury it in a mechanical discourse of bioenergetics, a dissonance apparent in the distance between the anthropomorphic terminology and the machine-like organism it describes.

The new bee is an evolutionary bee for whom (as for all social insects) society is the individual and whose relationship to the hive is equal to that between the cell and the body. Out of these metaphors comes a compelling narrative of bee evolution in which selective pressures operate at the level of intercolony competition for food, foraging area, and other resources, a narrative supported by the absence of observable tension within the hive.

38