Insectopedia (54 page)

Kawasaki tells us that his mission is to heal the family. He wants to open the hearts of men and bring them closer to their sons. Fathers have become cold; their hearts are hard and dry. Their lives are deadening. They have no interest in their children. They don’t feel the connection. On his website, he offers to lend stag beetles at no charge. Perhaps insect friends will bring families together. He remembers the love he felt when he was a boy hunting beetles in the mountains around Wakayama. “I want to nourish their hearts,” he says.

Online, Kawasaki Mitsuya calls himself Kuwachan, a sweet name that a parent might give a child who is fond of insects:

kuwa

from

kuwagata

,

or stag beetle, and

-chan

a common diminutive suffix. Across the top of his home page is a brightly colored cartoon of a small boy in full insect-collecting kit. It is Kuwachan as he remembers himself in the 1970s, white hat, hiking boots, water canteen and collecting box slung around his neck, a butterfly net grasped like a flag in the breeze, its pole thrust into the earth. Kuwachan the insect-boy, high on a hill, back to the viewer, face upturned to the blue of the sky, arms thrown wide to the world and its possibilities.

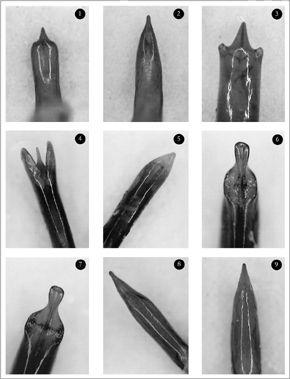

A few days earlier, CJ and I had spent the day in Hakone, a popular spa town in the hills southwest of Tokyo. We were visiting Yoro Takeshi, neuroanatomist, best-selling social commentator, and insect collector. Like Kuwachan, Yoro welcomed us into his home and filled the day with wide-ranging conversation. Yoro is in his late sixties, but he pursues his insects with youthful energy, augmenting his enormous collection with expeditions to Bhutan, chasing weevils as well as the more extravagant elephant beetles. When CJ and I arrived at his house, he was examining a set of burnt-orange penises from type specimens on loan from the Natural

History Museum in London, using his state-of-the-art microscopes and monitors to reveal species-defining morphological differences that made me wonder about human limitations that had never previously crossed my mind.

Like Kuwachan, Yoro has loved insects since he was a child. Like Kuwachan, he told us that they affected him profoundly. After collecting for so many years, he now has “

mushi

eyes,” bug eyes, and sees everything in nature from an insect’s point of view. Each tree is its own world, each leaf is different. Insects taught him that general nouns like

insects, trees, leaves

, and especially

nature

destroy our sensitivity to detail. They make us conceptually as well as physically violent. “Oh, an insect,” we say, seeing only the category, not the being itself.

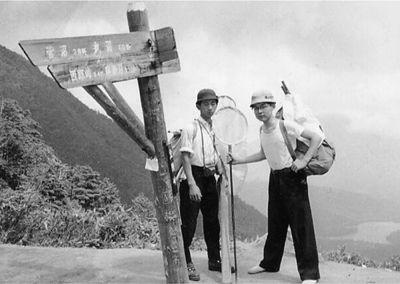

Shortly after returning to Tokyo, CJ and I came across this photograph, evidence that Yoro, like Kuwachan, was once an insect-boy, a

konchu-shonen.

There he is on the right, resolutely setting off into the hills of Kamakura soon after the Second World War, a time of devastation and hunger, but a time nonetheless of adolescent exploration and freedom.

We met Yoro at his newly built weekend home, a quirky barnlike construction designed by the “Surrealist architect” Fujimori Terunobu that—with its strip of meadow sprouting from the apex of the roof—suggests both

Anne of Green Gables

and

The Jetsons.

The house reminded us of those out-of-joint structures that populate

Spirited Away, Howl’s Moving Castle

, and other epic animations by Hayao Miyazaki, structures that fill an elaborate universe that is somewhere and some when unknown but still somehow instantly familiar.

The connections were not accidental. It emerged that not only are Yoro Takeshi and Hayao Miyazaki close friends but that Miyazaki, too, cultivates a passion for insects that began with a childhood as a

konchu-shonen.

What’s more, it seems Miyazaki also enjoys collaborating with avant-garde architects. He and the artist-architect Arakawa Shusaku have drawn up plans for a utopian town whose houses are not unlike the one in Hakone to which Yoro gets away from the city and in which he keeps his insects. Theirs is a distinctly hippie vision of social engineering,

motivated by some of the same worries about alienation and some of the same yearnings for community that preoccupy Kuwachan. Theirs is a town where children can escape what all of these men see as the profound estrangement of Japan’s media-saturated society and where they can rediscover a golden childhood of play, experimentation, and exploration in nature, where children—and adults too—can learn (again) to see, feel, and develop their senses.

2

Kawasaki, Yoro, and Miyazaki were only the first of many insect boys that CJ and I encountered in Japan. It seemed that wherever we went, we met

konchu-shonen

, both large and small. We came across a famous one in Takarazuka, the home of the celebrated all-women theater company, with its long-lasting idols and mass following of devoted female fans. We couldn’t get tickets to a performance, but no matter. We were in town for another attraction, the Tezuka Osamu Manga Museum, a perfect small museum dedicated to the life and work of the acknowledged god of manga (and innovator in anime), who died in 1989.

If Miyazaki is the current superstar of anime, Tezuka was the artistic genius who used the narrative techniques of cinema to transform the printed page, creating a dizzyingly kinetic comic-book form that accommodates every conceivable subject matter and emotion. He, too, was a passionate insect collector, so passionate that he named his first company Mushi Productions, incorporated a cute version of the Sino-Japanese character for the word

mushi

into his signature, and populated his stories with butterfly-people, erotic moths, beetle robots, and endlessly varied metamorphoses and rebirths. Sure enough, there was Tezuka fully decked out as Insect Boy in the museum’s introductory video, ready for adventure, an early intimation of Astro Boy, the android superhero who is still one of Tezuka’s most marketable creations (and who, in the intricate, multiauthored ways of such creativity was, Tezuka recalled, inspired by Walt Disney’s Jiminy Cricket—a different kind of insect-human).

“This place was a space station, a secret jungle for explorers to discover,” Tezuka’s text reads; in the background melodic harpsichords and the chirps of birds and crickets. It was “an infinity where imagination could expand forever.” The sky is a dreamlike azure; the boys are in sepia. As the images floated by, CJ translated: “I was bullied as a child and thrust into war. I cannot say everything was great, and I don’t want

to dwell in the past. But looking back now, I’m grateful to have been surrounded by so much nature. My experience of running freely in mountains, rivers, and meadows and of the insect collecting in which I was so absorbed gave me unforgettable memories and imbued in me a feeling of nostalgia as a deep part of my body and my heart.”

Tezuka won’t dwell in the past, but he won’t give up that longing either, the sweet-sad pleasure that feeds on the impossibility of erasing the distance between me then and me now. It’s an absence easy to reproduce: easy as an azure sky and two sepia boys. It’s an absence easy to fill, too, if not with a mail-order

kuwagata

then with an afternoon spent

mushi

hunting.

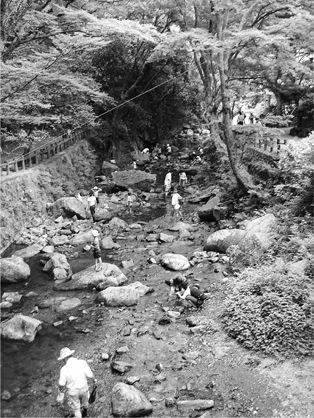

CJ and I shade our eyes as we step out of the insect museum in Minoo Park, the same park where Tezuka the

konchu-shonen

first collected insects with his sepia friends. Here, all around us, under the bluest sky, are living families, here in the here and now, fathers and sons (and a few women and girls also, although they rarely show up in the memories or longings of

konchu-shonen

). Here they are in the bright afternoon sun, fully equipped

konchu-shonen

, spread out along the shallow river, searching for bugs—water striders, water boatmen, crabs, too—serious but happy, balanced on rocks, dipping toes into the cool water, splashing around, emptying nets, showing their grown-ups what they’ve found (not much, as it’s too early in the summer).

The children are collecting specimens for their school summer projects, and their fathers are there to help them, also in shorts and hats, also holding the nets and buckets, which they got for ¥2,000 (U.S.$20), a price that includes a lab session at which anything they find can be pinned, ID’d according to the full-color

zukan

(field guide), and turned into a specimen. It’s a sunny day of

kazoku service

, family service. A day to fulfill the promise of Kuwachan’s poems, a day for boys to use their nets to catch the memories for a lifetime and men to learn again how to be fathers as they relive what it felt like to be a son.

And speaking of fathers and sons, here is one more insect-boy. He’s standing with the inflatable rhinoceros beetle that his father just bought for him at the summer festival. They’re on their way home, late at night outside the Minowa metro station in northeast Tokyo, a boy and his father under the streetlights, stopping to chat with a stranger and pose for a photo.

That’s just camera shake during a long exposure. But it’s as if he’s hardly there. The little boy with his giant

kabutomushi.

He’s melting into the lights, already inaccessible, already an object of desire, longing, and regret.