Insectopedia (24 page)

As did modern antisemitism, eugenics, and what Germans were beginning to call

Rassenhygiene—

race hygiene, rather than social hygiene—captivated thinkers across the political spectrum.

24

It can be difficult now to recognize the idealism tied up in this form of social engineering. And it can be hard also to appreciate the extent to which even the most catastrophic of outcomes was contingent. Darwinism did not have to devolve to a crude sociology of competition; eugenics required commitment to neither nation nor a hierarchy of races, only to the scientific improvement of a given population.

25

But what is so stunning about this moment is how the confluence of these ideologies—and the associated transformation of politics into a form of biological science—proved so irresistible and how it took so many people to such unnerving places.

Degeneracy, science, nation, and race. Nossig stayed within the Zionist Organization for a decade following its first congress in 1897. He threw himself into activism but was more and more at odds with a leadership he considered elitist and anti-democratic. He vied constantly for the diplomatic ear of anyone who might hold a key to the gates of Palestine. He negotiated with British, Polish, and American officials. But his most

persistent contacts were with the Ottoman Empire, which at the time controlled the territory of Palestine. His ceaseless travel to clandestine meetings produced anxiety, even among his allies, and a sense of unreliability and danger around his person that would precede him all the way to Warsaw. Even worse perhaps, he failed to disguise his distaste for his Zionist rivals and so created enemies, powerful ones, through displays like the public showdown in Basel in 1903, when he denounced Herzl for his “

jüdische Chuzpeh.

”

“All nations got their countries thanks to conquest or labor,” he wrote that year in language that could only deepen his isolation; “only the Jews, who buy and sell everything, bought themselves a homeland too.”

26

Nossig’s most consuming project at this time was the statistics enterprise. The first task—a task never completed—was to demographically identify the Jewish people; the second was to diagnose their condition. The people were sick: life in the primitive East (or, for later writers, the degenerate West) made this plain.

27

Here again, Jews and antisemites found common ground, even if, for Jews, sickness demanded regeneration and transformation, not extermination.

28

In 1908, Nossig finally left the Zionist Organization, increasingly uncomfortable with what he thought was its extreme and indistinctively non-Jewish nationalism and its counterproductive and unethical “cult of power” in relation to Palestinian Arabs.

29

Believing also that the organization was neglecting settlement, he established a new broad-based colonization body, the Allgemeine Jüdische Kolonisations Organisation (AJKO), which he hoped would become an institutional rival to the Jewish Agency, the official organization. At that point, many Zionists envisaged a “home for the Jews” within the framework of the Ottoman Empire and were encouraged by the sultanate’s developing policy of limited territorial autonomy based on religion and ethnicity.

30

In the years leading up to the First World War, Nossig maneuvered aggressively to get the Ottomans to recognize the AJKO, not foreseeing the empire’s collapse and the British capture of Palestine. Even though German Jews overwhelmingly allied as patriots with the Central Powers in the First World War, Nossig’s agitation was sufficiently high profile to mark him as a German agent—a whisper circulated by British and American diplomats in the region, as well as by the Zionist Organization

itself, and a rumor that would have an altogether more sinister resonance when it resurfaced twenty years later.

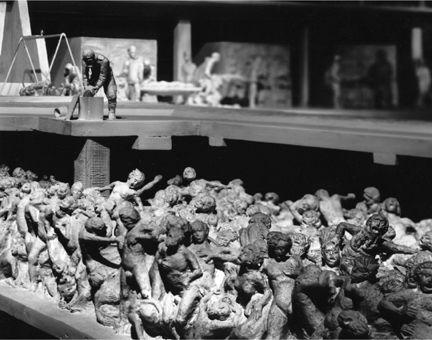

As conditions deteriorated during the 1930s, Nossig threw himself into peace activism, even organizing a peace movement for young Jews. But eventually he felt forced to leave Berlin for Prague, where he devoted himself once more to his sculpture. Europe was becoming increasingly precarious for Jews, but he somehow succeeded in publicly exhibiting in Nazi Berlin a scale model of a monument he planned to erect on Mount Zion in Jerusalem. It was called The Holy Mountain and consisted of more than twenty outsize statues of biblical characters, a symbolic landscape of Judaism, now lost, which I imagine was peopled by figures as vigorous and resolute as his Wandering Jew.

Nossig is in his seventies by this point, and as Almog tells it, is offered asylum in Palestine “as a veteran Zionist.”

31

But he doesn’t go. The old man who has spent so much of his life working for Jewish emigration refuses to leave without his sculptures. The next we hear he has arrived in Warsaw as a refugee.

To Marek Edelman, a ZOB commander in the Warsaw Ghetto, the execution of “the notorious Gestapo agent, Dr. Alfred Nossig,” was a necessary action in “a programme designed to rid the Jewish population of hostile elements.”

32

I like to think the contrast between Edelman’s military language and his retention of Nossig’s title signals unease. But it could just as easily be the voice of bureaucracy.

Remarkably, Edelman survived the uprising. Days after emerging from the sewers of the razed ghetto with a few battered comrades, he took a tram through the bustling streets of Aryan Warsaw and found himself staring at his own image. It was a poster that had appeared immediately following the uprising, and on seeing it, Edelman was instantly “seized by the wish not to have a face.”

33

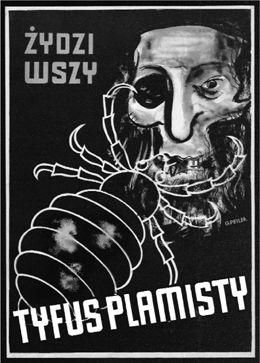

“Jews—lice—typhus”—the poster that confronted Edelman shows a monstrous louse crawling into a hideously deformed “Jewish” face. It was part of a concentrated campaign that accompanied the liquidation of

the ghetto.

34

Edelman’s panicked reaction testifies to the potency of the image. He drags himself out through the bowels of the ghetto to find that his racialized self, the parasitic louse, has been forced into daylight too. It truly is a shock of recognition.

We already know something of the darkening histories buried in this horror. We, too, recognize the louse and its biology. We remember that there was a moment, not long before, when Jews like Edelman and Nossig could imagine themselves as children of emancipation, as heirs to European science and letters. We know they saw that the old judeophobia had become a new antisemitism. We know that many reacted to this new antisemitism by abandoning their dreams of assimilation and grasping at the Zionist nation.

We didn’t know—though it’s surely no surprise—that in 1895 (the year after Nossig published his

Social Hygiene of the Jews

) the German physician Alfred Ploetz responded to the general fear of social and racial degeneration in the wake of industrialization by publishing

Die Tüchtigkeit unsrer Rasse und der Schutz der Schwachen

(

The Fitness of Our

Race and the Protection of the Weak

), the founding statement of German

Rassenhygiene

, in which he warned that “traditional medical care helps the individual but endangers the race.”

35

We also didn’t know that in 1904 and 1905—just after Nossig and his colleagues had launched the Association for Jewish Statistics and prepared its publications—Ploetz, also in Berlin, established the journal and institutional apparatus of the new racial-hygiene movement. It’s time to return to the problem we started with. How could the

Reichsführer

say those things? Do you remember? “Antisemitism is exactly the same as delousing. Getting rid of lice is not a question of ideology. It is … a matter of cleanliness, which now will soon have been dealt with. We shall soon be deloused.”

Perhaps Himmler was indulging in an intimate irony with his men. As is well known, prisoners at Auschwitz were treated to an elaborate charade. Those selected for death were directed to “delousing facilities” equipped with false-headed showers. They were moved through changing rooms, allocated soap and towels. They were told they would be rewarded for disinfection with hot soup. Despite the fears of disease, the hunger for cleanliness, and the routine character of such hygienic procedures for migrants, there is evidence of considerable confusion and recalcitrance. The prisoners massed uncertainly in the shower room. Overhead, unseen, the disinfectors waited in their gas masks for the warmth of the naked bodies to bring the ambient temperature to the optimal 78 degrees Fahrenheit. They then poured crystals from the cans of Zyklon B—a hydrogen cyanide insecticide developed for delousing buildings and clothes—through the ceiling hatches. Finally, the bodies, contorted by the pain caused by the warning agent (a life-saving additive in other circumstances), were removed to the crematoria.

36

In this grotesque pantomime, the victims—and we must remember they were not only Jews—move from objects of care to objects of annihilation. To diseased humans, delousing promises remediation, a return to community, a return to life; to lice, it offers only extermination. Too late, the prisoners discover they are merely lice.

The politics of life as the politics of death. Life stripped bare of its humanness. (Even if this work of turning humans into lice also makes lice human.) Such things were possible not because of the inferiority of the Jews—a fact never securely established: how could they be so powerful

and so subhuman all at once?—but because of their unsettling alterity.

37

This is the moment when sovereign power is vested in the medical professionals. Not the Jewish physicians like Nossig (and Edelman), of course, but others who had debated the science of national survival in ways that were at once similar and different.

38

Himmler’s language contains metaphor, euphemism, and at some level, I suspect, a statement of belief. The word the Nürnberg lawyers translate as “getting rid of”—“getting rid of lice is not a question of ideology”—is

entfernen

, to remove or make distant, one more euphemistic ambiguity in the self-consciously legalistic series that has Himmler elsewhere evade naming the killing, talking instead of “mortality rates,” “special treatment,” “emigration,” and “known tasks.”

39

Yet this alone cannot explain the literalization of Himmler’s speech that takes place in the gas chambers. As well as metaphor, euphemism, and belief, there is the most material of histories underlying his parasitic insects. It is a history that finally dissolves the distinction between those things that enter from outside (the individual body, the body politic, the foreign body) and those that are always present within (the parasitic animal

inside). It is the final collapse of distinction between human and insect; the collapse that allows for extermination.

For Germans, the association of Jews with disease was a long one, encased in the memory of the Black Death as a

Judenfieber

, a Jewish sickness, penetrating from out there, beyond the eastern borders.

40

Of the modern black deaths, it was the lice-borne typhus, with its sudden and catastrophic mortality rate, that was the most feared, and even though by 1900 it was “virtually dormant,” its menace was palpable—and also locatable: in Jews, Roma, Slavs, and other “degenerate” social groups associated with “the East.”

41

The national fear of disease only intensified with the rise of the bacteriological sciences. Even though Robert Koch, the pioneer of German bacteriology and winner of a Nobel Prize in 1905 for his work on cholera and tuberculosis, refused to link pathogens with race (instead emphasizing transmission), his research was fully compatible with the new ideologies of racial hygiene, and introduced a logic of extermination that would resonate ever more strongly during succeeding decades.