Insectopedia (27 page)

Honeybees, said von Frisch, though so tiny and so different, possessed language, the capacity long definitive of humanity. Through a series of elegant experiments carried out over nearly half a century, he showed that they communicated symbolically, that, in a manner more complex than that of any other animals apart from humans, they drew

on experience and memory to convey information to each other and to their fellows.

More than ninety years after his first reports, these discoveries are still exciting. And they are made more so by von Frisch’s way of telling. By inclination and early training a naturalist, he offered nature not in today’s technical language of genomics but in his own deeply personal language of bees, a remarkably affective language that imbued his subjects with purpose and intentionality, that made them appealing and familiar.

Von Frisch offered a science of “what animals do, and how and why they do it” that was as comfortable with ontological difference and abiding mystery as it was with the more familiar scientific impulse toward revelation.

1

Unashamed in his confessions of affinity, he made readers believe—just as he did himself—that they could understand bees, psychologically and emotionally. He turned his public into animal analysts. And in doing so, he gave new impetus—though, perhaps, despite himself—to the Darwinian notion that not only the morphological but also the behavioral, moral, and emotional basis of human existence could be found in the lives of nonhuman animals.

2

Von Frisch spoke for honeybees. And he made them speak. He didn’t just give them language; he translated it. Is there anything that is more irresistible?

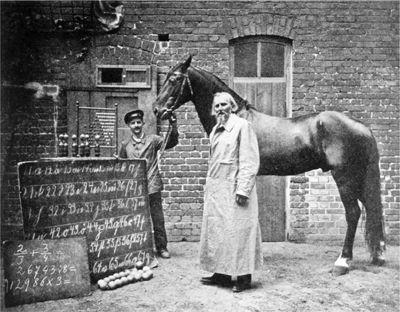

Nonetheless, these affinities were deeply fraught in a discipline barely born yet already haunted by the specter of fallibility. Ethology’s ghost was Clever Hans, the celebrity horse whose cleverness unfortunately lay not in mathematics but in an uncanny sensitivity to the nonverbal cues of his unwitting trainer. Clever Hans’s much-publicized debunking by the psychologist Oskar Pfungst in 1907 pushed questions of animal cognition to the very margins of scientific legitimacy and made it clear that ethology was at mortal risk from the allure of its subjects.

3

It was a foundational temptation to which the resolutely anti-psychological behaviorists would not succumb. But it was the seduction to which von Frisch, caught between affect and object, preoccupied, as he himself wrote, by the interplay between “psychological performance and the physiology of the senses,” would forever be in thrall.

4

Because von Frisch loved his bees. Loved them with a gentle passion. Tended and nurtured their generations. Warmed them in his cupped

hands when the brisk air stiffened their wing muscles. Held them as his “personal friends.”

5

They were his bees in the way that anthropologists of the past may have fancied the remote tribes among which they lived to be their tribes. That same heady mix of science, sentiment, and proprietorial pride, the same willingness to assume responsibility for another’s fate.

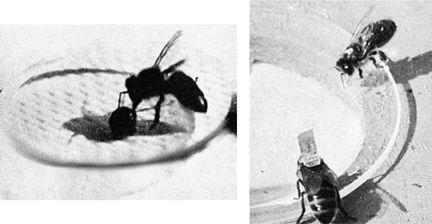

So even as he took such care over the tiny creatures’ welfare, von Frisch would lovingly (with another love), painstakingly (with a professional patience), and delicately (with such safe hands) snip their antennae, clip their wings, slice their torsos, shave their eye bristles, glue weights to their thoraxes, and carefully paint shellac over their unblinking eyes, modifying their bodies, mutilating their senses, manipulating their behavior according to the experiment’s requirement, reconciling his will to suture the yawning gap that separated human from insect with his unspoken assertion of a natural sovereign power.

In April 1933, the Nazi-dominated Reichstag passed the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service. Jews, spouses of Jews, and political unreliables could now be legally dismissed from the universities.

6

By then, von Frisch was director of the new Rockefeller-funded Institute of Zoology at the University of Munich and a leading figure in German science. Years before, in the landscaped and columned courtyard of the institute, he had, as he recalled in his memoir, fallen “irresistibly under the spell of the honey-bee.”

7

His enchantment by those he would come to call his little “comrades” had in fact begun even earlier. In 1914, with a magician’s flair, he publicly demonstrated what now seems the rather unsurprising truth that honeybees—whose livelihood, after all, depends on their identification of flowering plants—are able to discriminate by color (despite being red-blind). Using the standard behavioral method of food rewards, he trained a group of bees to identify blue plates. He then showed them small squares of colored paper and watched delightedly as they congregated “as if by command” for his skeptical audience.

8

But it was in the garden in Munich that the bees first danced for him: “I attracted a few bees to a dish of sugar water, marked them with red paint and then stopped feeding for a while. As soon as all was quiet, I filled the dish up again and watched a scout which had drunk from it after her return to the hive. I could scarcely believe my eyes. She performed

a round dance on the honeycomb which greatly excited the marked foragers around her and caused them to fly back to the feeding place.”

Although beekeepers and naturalists had known for centuries that honeybees communicated the location of a food source among themselves, no one knew how. Did they lead one another to the nectar? Did they diffuse scent trails? “I believe,” von Frisch wrote more than forty years later, that this “was the most far-reaching observation of my life.”

9

Under the civil service law, von Frisch and his academic colleagues—as well as all other civil servants in the Reich—were required to produce documentary proof of their Aryan ancestry. Already suspect for his willingness to sponsor Jewish graduate students even when their theses were far from his own specialties, von Frisch found himself in an even more dangerous dilemma.

10

His mother’s mother, now deceased, the daughter of a banker and the wife of a philosophy professor, was a Jew from Prague. At first the university protected its star zoologist, arranging for his safe classification as “one-eighth Jewish.” But imagine the virulent mixture of ideology and ambition that began to ferment, fed by a rigid institutional hierarchy and the lack of opportunity for advancement among scholars locked out of academic privilege despite their years of training. In October 1941, the campaign against von Frisch succeeded in forcing his reclassification as “second-grade

Mischling

”—one-quarter Jewish—and securing the order for his removal from his post.

As we know, von Frisch survived the Nazis. Inevitably, though, it was far from straightforward. Influential colleagues mobilized on his behalf, arranging a platform in

Das Reich

, a new weekly in which Goebbels contributed the editorials. Von Frisch wrote about the national-economic contribution of the Zoological Institute and how its work was vital to the resilience of the home front.

11

Eventually, though, if in somewhat tortuous fashion, it was the bees that saved him. For two years, an outbreak of the parasite

Nosema apis

had ravaged German hives. Both the national honey crop and agricultural pollination were threatened. Through the intervention of a highly placed ally, von Frisch was appointed as a special investigator, and a panicked Ministry of Food was induced to defer his dismissal from academia “until after the war.”

12

The indifference of the honeybees to politics did not prevent their recruitment to the National Socialist war effort. The ministry soon

expanded the

Nosema

remit to include a search for ways of persuading bees to rationalize pollination by visiting only economically desirable plants. Years before, von Frisch had experimented with scent guidance—training bees to respond to a particular odor before freeing them to visit the associated flower—but he had been unable to generate commercial interest. This time, galvanized by looming calamity, national enthusiasm, and news of a large-scale Soviet research project along similar lines, the Organization of Reich Beekeepers rushed to sponsor his work.

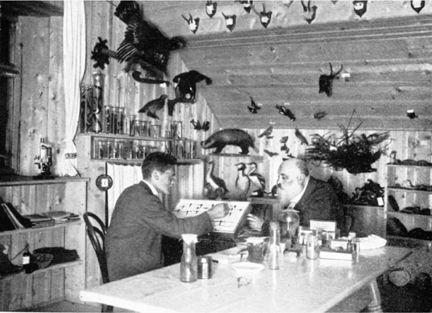

Exhausted by the intensifying air war on Munich, von Frisch and his lifelong co-worker, Ruth Beutler, evacuated to the village of Brunnwinkl on the shore of Lake Wolfgang, southwest of Salzburg. This was where von Frisch had spent his childhood summers, and attached to the family house was the natural history museum he had founded as an eager seventeen-year-old. It was here, pursuing adolescent obsessions, that young Karl had enrolled relatives and family friends in scouring the nearby woods and shoreline for local fauna. It was here, at the old mill on the edge of Lake Wolfgang, under the quiet hand of his uncle, the prominent Viennese physiologist Sigmund Exner, that he developed the classical skills in observation and manipulation that would characterize his experimental research.

And it was also here, here among the animals, that von Frisch found his “reverence before the Unknown,” less a formal religious conviction than a commitment to a pantheistic relativism. “All honest convictions deserve respect,” he insisted, “except the presumptuous assertion that there is nothing higher in the world than the mind of man.”

13

And it was here, as he tells it in straightforward yet often lyrical prose, that his liberal Catholic family—doctrinally liberal in an era when Austrian biologists were routinely dismissed for espousing evolution—created a bourgeois haven, a home for science and the arts, for the gentle satisfactions of polite culture far from the upheavals of early-twentieth-century Mitteleuropa: his spirited mother and his caring if reserved father, his three older brothers, all preparing merely for the uneventful unfolding of long and distinguished academic careers.

And it was here, in the cocoon of family memory, as the Allied bombs rained firestorms on Munich and Dresden and as the air thickened over Auschwitz, that von Frisch and Beutler took advantage of their Reich permits to revisit the work on bee communication that he had laid aside some two decades earlier.

In those long-ago studies in the courtyard of the Institute of Zoology, von Frisch had identified two “dances”—he named them the round

dance and the waggle dance—and concluded that bees used the former to indicate a source of nectar and the latter to indicate a source of pollen. Beutler had continued this work in the intervening years but had begun to doubt the hypothesis. Resuming their experiments together in 1944, they discovered that when they positioned the feeding dishes more than 100 yards from the hive, it didn’t matter what substance the bees were carrying: on their return, they all performed waggle dances. Rather than a descriptor of material, the variation they observed in the dances must be the bees’ way of communicating the far more complicated information of location. This ability to accurately describe distance and direction “seemed,” von Frisch wrote, “altogether too fantastic to be true.”

14