I'm Not Hanging Noodles on Your Ears and Other Intriguing Idioms From Around the World (4 page)

Read I'm Not Hanging Noodles on Your Ears and Other Intriguing Idioms From Around the World Online

Authors: Jag Bhalla

A dog and a monkey

Japanese: to be on bad terms

NOT SUCH GOOD FRIENDS

- To smell like water:

unfriendly, formal situation (Japanese) - Migratory crow:

a fair-weather friend (Hindi) - Those who seek a constant friend go to the cemetery:

proverb (Russia) - Meal finished, friendship ended:

someone who eats and runs (Spanish) - Meeting the Buddha in hell:

a friend in need is a friend indeed (Japanese) - Monkey’s friendship:

fickle friendship (Hindi) - A quarrel in a neighbor’s house is refreshing:

proverb (India) - A guest and a fish after three days are poison:

proverb (French) - A dog and a monkey:

to be on bad terms (Japanese) - Porch dog:

a hanger-on, parasite (Hindi) - A honeyed knife:

a secret enemy (Hindi) - A sleeve:

an enemy in the guise of a friend (Hindi) - Cannot share the same sky:

irreconcilable, deep hatred for (Chinese) - To fix the cake:

to patch things up (Spanish)

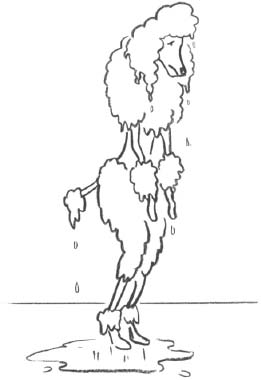

To stand like a watered poodle

German: to be crestfallen

ANIMALS

Here the donkey falls

L

ANGUAGE WAS THOUGHT

to be uniquely human. Something that distinguished us from other animals. I like that way of putting it. Since we too often forget that we, too, are animals. As Christine Kenneally reports in her wonderful book on the development of language,

The First Word,

amazing animals are helping us redefine how we think, not only of them, but also of language itself.

1

Scientists used to think of language as a monolithic capability; however, animals are showing us that it is more accurately thought of as a suite of capabilities. And it turns out that many of those abilities are shared with other animals.

At the low end of animal communications, Kenneally notes that vervet monkeys have a preprogrammed three-alarm call vocabulary. The equivalent of “Yikes! There’s an X!”, where “X” could be a leopard, an eagle, or a snake. Further up the communication chain is Kanzi,

*

an alpha male bonobo (pygmy chimpanzee). He understands a couple of thousand words and can communicate using 300 gestures, a custom keyboard (we’re not talking

QWERTY

here), and pictogram sheets.

Remarkably, Kanzi is a word coiner. He was able to creatively fill a gap in his vocabulary. He spontaneously combined “water” and “bird” to form “waterbird” to refer to a duck. Kanzi has shown that bonobos can acquire language skills equivalent to a human infant (about two and half years old). And even more so than for other infants, the expression “cheeky monkey” seems most apt. One of the new sentences Kanzi correctly understood was, “Can I tickle your butt?” That might not be so surprising for those familiar with other famous bonobo characteristics. A final point on the

monkey business

of ape linguistics is related to my favorite guinea pig name. In a wonderful piece of punery, researchers at Columbia University called one of their simian subjects Nim

*

Chipsky, in humorous homage to Noam Chomsky, the founder of modern linguistics.

Language capabilities aren’t confined to species that we consider our near relatives. Some researchers believe that the prize for the animal with the most advanced grasp of human syntax and semantics should have gone to Alex, an African gray parrot in the lab of Irene Pepperberg at Brandeis University. He was no

bird brain

and could identify 50 objects and use conceptual categories for color, shape, and number.

**

All of these had been thought to be uniquely human abilities. Ironically, linguists call the type of language that Pepperberg used to talk to Alex a “pidgin.” Alex was estimated to have the language skills of a two-year-old human and the cognitive abilities of a six-year-old.

3

As Jonah Lehrer reports in his intriguing book

Proust Was a Neuroscientist,

bird brains have also proved crucial in groundbreaking brain science. Neuro-anatomists first directly observed the once-thought impossible, the formation of new brain cells in bird brains. In a wonderful connection with Charles Darwin’s la-la theory, it seems that to sing their complex melodies, male birds need to make new brain cells every day.

4

And this need is influenced by environmental factors. Birds stuck in sterile lab environments have no need to and don’t make new brain cells. This work has been replicated in primate brains and, by extension, applies to us. A whole new field of neurogenesis is emerging, and among its initial areas of interest is a new class of antidepressant drugs aimed at improving neurogenesis. It seems that new brain cells, some of which come from new experiences and needing to learn new things, can make us happier! We are neophiles built to be happier when we are stimulated.

To summarize the state of the art of “woo-woo theory,” I can put it no better than George Miller, its founder: “Creative courtship may have also played upon neophilia, a fundamental attentional and cognitive attraction to novelty…. Darwin argued that neophilia was an important factor in the diversification and rapid evolution of bird song. Primate and human neophilia is especially strong…. Partners who offered more cognitive variety and creativity in their relationships may have had longer, more reproductively successful relationships…. A good sense of humor is the most sexually attractive variety of creativity, and human mental evolution is better imagined as a romantic comedy than as a story of disaster, warfare, predation, and survival.”

*

5

He doesn’t go into the fact that many of today’s romantic comedies involve their share of disaster and gender warfare….

Any tale of animal linguistics wouldn’t be complete without

a shaggy dog story.

“Rico,” a border collie at the Max Planck Institute in Germany, could interpret the meanings of hundreds of words and could even infer the meanings of new ones. When commanded to enter a room and retrieve an object he had never seen before, he was correctly able to pick the one object he hadn’t previously learned the word for. And let’s not forget “Lassie,” who had a particularly useful command of disaster-

**

related vocabulary. Daniel Dennett, the famous cognitive scientist, describes words “like sheepdogs herding ideas.”

It appears that other species share another important aspect of human communications. Kenneally reports on what happened when one ape trained in sign language

first met another equally proficient ape. They had a sign-shouting match. Neither ape was willing to listen. The French have a great expression for it, “the dialogue of the deaf.”

At least at the moment, it’s still not controversial that humans are the only species using complex symbols. And no non-human animal has ever been observed using an idiom. That, at least, is still uniquely human.

Even though animals don’t use idioms, they are very widely used in them:

When we

smell a rat

or feel that

something is fishy,

a similarly suspicious Frenchman would be concerned that “there’s an eel under the rock,” a cautious German would worry that something wasn’t “totally pure rabbit,” and an Italian would say, “Here the cat broods.” Our cats have more time to brood, since they have nine lives; Italian canines are similarly, though slightly less blessed, as they have “seven lives like a dog.” While it can

rain cats and dogs

here, German weather is less inclusive—it only “rains young dogs.”

We have difficulty with careless penmanship seen as

chicken scratch.

For the French, it’s cats that have poor paw control: “cat’s writing.” When an English speaker is having difficulty communicating because she has

a frog in her throat,

a similarly challenged Frenchman’s throat contains a cat. Rather than

eat crow,

a Frenchman “swallows a toad.” For French cats, being swallowed isn’t all they have to worry about; when we have

other fish to fry,

the French more cruelly have “other cats to whip,” and when we

hem and haw,

Russians “pull the cats’ tail.” To say someone is forgetful or

has a head like a sieve

in Yiddish, is to call that person a “cat head.” The Japanese expression “a cat defecates” seems a particularly cat-headed way of saying to “sneakily put something in your pocket.” Pickpockets targeting the Japanese, beware.

Cleaner than a frog’s armpit

Spanish: broke

When a German wants to indicate that something is important, he says “there the donkey falls.” And after the donkey has fallen, the same German might “feed barley to the tail when the donkey is dead”—the equivalent of our

bolting the barn door after the horse has gotten out.

*

Speaking of expired equines, when we

beat a dead horse,

the Chinese are crueler and will “beat a drowning dog.” Similarly, unforgiving Chinese “throw stones on a man who has fallen in the well.” When we

let the cat out of the bag,

the Japanese “reveal the legs of a horse,” the Chinese only “show the horse’s hoof.” As we hope to

kill two birds with one stone,

Italians “catch two pigeons with one fava bean,” Germans “hit two flies with one hand clap,” and Hindi speakers “get a mango at the price of a stone.”

When we admonish someone for

being a chicken,

Arabs would call the same person “camel hearted.” Similarly, scared Italians “have the heart of a hare,” reticent Russians are told “not to be a rabbit,” and timid Hindi speakers are called a “wet cat.” Rather than being afraid, Italian chickens apparently aren’t very bright; when an Italian says someone is “really a chicken,” he means that person is easily fooled.

BIRDS

- To have a bird:

to be nuts, crazy (German) - Like a heavenly bird:

lead an untroubled life (Russian) - Walk like a golden-eyed bird:

to strut about (Russian) - The only thing missing is the bird’s milk:

having everything under the sun (Russian) - To throw a chicken at oneself:

to run away (Spanish, Chile) - To die chicken:

to not reveal a secret (Spanish, Chile) - Like a perch in a chicken coop:

insulted, pooped on (Spanish, Mexico) - Chicken’s eye point of view:

having limited vision (Yiddish) - Plucked out like a chicken:

done in, spent (Yiddish) - Don’t be a tawny owl:

don’t be stupid (Italian) - Stop being the owl:

stop flirting (French) - To carry owls to Athens:

useless (German) - An owl egg sunny-side up:

a practical joke (German) - Son of an owl:

an out-and-out fool (Hindi) - To eat owl’s flesh:

to act idiotically (Hindi) - Love the house, love the crows:

love me, love my dog (Chinese) - White crow:

a rare find (Russian) - Pay for the ducks:

pay unfairly (Spanish, Mexico) - To be duck:

to be broke (Spanish, Peru) - Ducks are falling already roasted:

it’s scorching hot (Spanish, Chile) - Those waiting for ducks to fall already roasted from the sky will be waiting a very long time:

proverb (Chinese) - To let a duck through:

to spread rumors (Russian) - A good duck:

someone easily fooled (Japanese) - Cold enough for ducks:

freezing cold (French) - To shoot at sparrows with cannon:

to overdo (German) - To get the partridge drunk:

to beat around the bush (Spanish) - Neither peahen nor raven:

neither fish nor fowl (Russian)

Ducks are falling already roasted

Spanish: it’s scorching hot

Tiger’s head with a snake tail

Chinese: things that start off well but end up poorly

FELINES

- Here the cat broods:

to be suspicious (Italian) - He’s a cat:

he’s smart, clever (Italian) - We’re four cats:

too few people for the task (Italian) - The cat goes to the lard so much that she loses her paw:

curiosity killed the cat (Italian) - There’s an ugly cat skin:

that’s a big problem (Italian) - Fine words don’t feed a cat:

talk is cheap (Italian) - I’ve got a cat in my throat:

I’ve got a frog in my throat (French) - Have other cats to whip

*

:

have other fish to fry (French) - There’s no reason to whip a cat:

not worth the fuss (French) - Don’t wake the sleeping cat:

let sleeping dogs lie (French) - Cat’s writing:

poor writing, chicken scratches (French) - A cat skinner:

a jerk (Spanish, Chile) - To give cat for rabbit:

to deceive (Spanish) - To bell the cat:

to do something difficult (Spanish) - To look for 3 or 5 feet on a cat:

the impossible (Spanish) - Cat weeping for the mouse:

insincere crying, crocodile tears (Chinese) - Trusting a cat to guard the bonito:

a fox in the henhouse, wolf among the chickens (Japanese) - Give gold coins to a cat:

cast pearls

*

before swine (Japanese) - A cat’s forehead:

a small area (Japanese) - To put a cat over oneself:

to feign ignorance (Japanese) - A cat defecates:

to pocket something stealthily (Japanese) - To pull the cat’s tail:

to hesitate (Russian) - Cat scratches on the soul:

something gnawing at one’s heart (Russian) - A cat’s leap:

a short distance (German) - To make a cat’s laundry:

to wash superficially (German) - Wet cat:

timid individual (Hindi) - Cat head:

to be forgetful (Yiddish) - To buy a cat in a bag:

to buy a pig in a poke, to be cheated (German) - To become a tiger:

a roaring drunk (Japanese) - A tiger cub:

a treasure (Japanese) - Let a tiger return to the mountain:

store trouble for the future and/or let sleeping dogs lie (Chinese)