I'm Not Hanging Noodles on Your Ears and Other Intriguing Idioms From Around the World (10 page)

Read I'm Not Hanging Noodles on Your Ears and Other Intriguing Idioms From Around the World Online

Authors: Jag Bhalla

- The five supreme gods:

a village court or tribunal (Hindi) - Five fires:

punishment, sitting in the sun in hot weather (Hindi) - Dissolution [of the body] into its five constituents:

death (Hindi)

SIX

- All six vital organs failing:

to be stupefied, stunned (Chinese) - Every sixth six months:

once in a blue moon (Hindi) - Six doors:

astonished, perplexed (Hindi) - Where six can eat, seven can eat:

there’s always room for one more (Spanish) - With three heads and six arms:

a superman (Chinese)

SEVEN

- Have seven lives like dogs:

have nine lives (Italian) - To sweat seven shirts:

to work hard (Italian) - To be in seventh heaven:

to be on cloud nine (Italian and French) - Seven mouths and eight tongues:

all talking at the same time (Chinese) - Seven inches in a forehead:

as wise as Solomon (Russian)

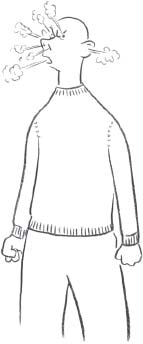

Smoke belches from the seven openings on the head

Chinese: very angry

- Standing there like a seven of spades:

looking stupid (German) - To vilify ancestors to the seventh generation:

to curse severely (Hindi) - Having seven husbands:

a loose woman (Hindi) - The seven utterances:

the marriage vows (Hindi) - Smoke belches from the seven openings on the head:

very angry (Chinese) - Seven trades but no luck:

proverb (Arabic) - Seven Fridays in a week:

can’t make up your mind (Russian)

EIGHT

- To become an eight:

to be confused (Spanish, Puerto Rico) - To make oneself into an eight:

to complicate one’s life (Spanish, Dominican Republic) - Eight bushels of talent:

have immense knowledge (Chinese) - Eight watches:

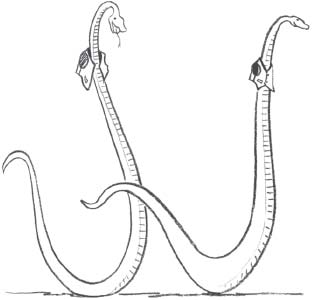

24 hours a day (Hindi) - Seven hands and eight legs:

too many cooks spoil the broth (Chinese) - Eight mouths and with eight hands:

to seem eloquent (Japanese) - A beauty to all eight directions:

a sycophant (Japanese) - To try whether it’s one or eight:

to put in full effort (Japanese) - Milk of every eighth day:

a cowherd’s payment in kind (Hindi)

Seven hands and eight legs

Chinese: too many cooks in the kitchen

NINE

- To have the nine treasures:

to have all that the heart desires (Hindi) - The nine continents:

the nine fabled regions of the world, all corners (Hindi) - Those who have ten miles to go, must regard nine as only halfway:

proverb (German) - A single hair from nine oxen:

a drop in the bucket (Hindi) - To have the nine treasures and twelve magical powers:

to have all that the heart can desire (Hindi)

TEN

- The ten directions:

eight points of the compass plus zenith and nadir (Hindi) - A smile will gain you ten more years of life:

proverb (China) - If bravery is ten, nine is strategy:

proverb (Turkey) - Not one of the timid ten:

not a wallflower, not timid (Russian) - Ten people–ten different colors:

it takes all sorts (Japanese) - Just like ten other people:

average ordinary person (Japanese)

MANY MANY

- Put oneself in a shirt of eleven rods:

bite off more than one can chew (Spanish) - To keep in one’s thirteen:

to persist in doing something (Spanish) - All sixteen [traditional] adornments:

elaborate makeup [of a woman] (Hindi) - The eighteenth:

one’s forte (Japanese) - Twenty-two misfortunes:

a walking catastrophe (Russian) - To put yourself on your thirty-one:

to get all dressed up (French) - To see thirty-six candles:

to see stars (French) - Of the thirty-six alternatives, running away is the best:

proverb (Chinese) - To sing the forty to someone:

to speak unpleasant truth (Spanish) - One man worth fifty-two:

a hero (Hindi) - Fifty-six knives:

a dangerous woman (Hindi) - To put someone to the hundred:

to excite (Spanish) - With a hundred lives:

with all one’s heart (Hindi) - One hundred holes and one thousand wounds:

state of ruin (Chinese) - To do the one hundred steps:

to pace the floor, be anxious (French) - To strike the four hundred blows:

to run wild, sow one’s wild oats (French) - Eight hundred lies:

completely untrue, a pack of lies (Japanese) - Ten thousand horses charging forward:

to rush headlong, to dive in (Chinese) - Ten thousand things rest:

it’s finished (Japanese) - To have a hundred thousand heads:

to be doggedly persistent (Hindi)

When the crayfish sings on the mountain

Russian: when hell freezes over, never

TIME

When dogs were tied with sausages

N

OW FOR SOME THOUGHTS

on time. Much of the popular literature on anthropological language comparisons tends to be snooty. It has the tone of first worlders looking down their noses (or “looking over their shoulders,” as the Germans would say) at “less developed” cultures. Time provides an example where a less developed culture could look down its nose at us. The Kawesqar are a tribe in Chile that have featured frequently in language debates. Charles Darwin encountered them before he wrote

On the Origin of Species,

and he noted that their survival in a cold damp corner of the Patagonia reinforced his belief that mankind is another animal well adapted to its environment.

The Kawesqar have no future tense in their grammar. Their past tense, however, is much more specific, more finely grained, and more evocative than ours. As reported in the

New York Times,

their grammar makes distinctions between “a few seconds ago, a few days ago, a time so long ago that you were not the original observer…but you know the observer yourself and, finally, a mythological past, a tense the Kawesqar use to suggest that the story is so old that it no longer possesses fresh descriptive truth but rather that other truth which emerges from stories that retain their narrative power despite constant repetition.”

1

These people could teach us a

thing or two

about the nature of the past. And about the nature of human memory.

Darwin knew what later scientists now understand neurobiologically, and what our legal system still refuses to acknowledge, that “memory is so deceptive that it ought not to be trusted.”

2

That’s something we should all know. Even though we might need artists to bring it to our attention. A task done admirably by Jonah Lehrer in

Proust Was a Neuroscientist,

in which he quotes Proust: “It is a labor in vain to try to recapture memory” and “The only paradise is paradise lost.” Lehrer elaborates: “Every memory is full of errors”; indeed, the act of remembering changes the memory (a process called

reconsolidation

). He continues: “Memories are not like fiction. They are fiction.”

3

We are built to remember relatively little and to creatively fill in the holes so that we seem to have a complete picture.

Another remarkable example of how differently time can be thought of comes from Stephen Pinker’s exhilarating book,

The Stuff of Thought

. In it he tells of the Aymara, a people whose metaphor for time is spatially the opposite of ours. Their culture views the past as being physically ahead of them and the future as being physically behind them.

4

The logic is that we can know the past, just as we can know what is in front of us. But the future is not so easily seen, like what’s physically behind us.

All languages are constantly changing (even discounting the effects of cultural chafing). John McWhorter, in his excellent book

Word on the Street,

describes how linguists look at this inevitable process. He means not just drift in word meanings (see below) or in the use of metaphors or idioms, but also in more fundamental ways like changes in rules of grammar and syntax. McWhorter’s position is that language is just a communication system “that is at all times in the process of becoming a different one.” This is more evident in speech than in text, because when writing we edit and consciously revise, rather than just communicate. This sort of change doesn’t compromise the fundamental ability to communicate.

One of McWhorter’s compelling examples is how the language of Shakespeare, in just 400 years, has become noticeably less understandable. Many readers will know that when Juliet stands upon her balcony, in what the Spanish might call the “pluck the turkey” scene, and pleads, “Wherefore art thou Romeo?”, she is asking “Why?”, which is what “wherefore” meant. Fewer readers, however, will likely understand the intended meaning in

Love’s Labor Lost

of: “with his royal finger thus dally with my excrement.” It’s not nearly as repulsively scatological or Freudian as it sounds to us today. Back then, excrement could mean any outgrowth, like hair, nails, or feathers. As McWhorter points out, someone fluent in Middle English, as spoken in Chaucer’s day, would have to learn modern English as if it were a completely foreign language.

Sol Steinmetz, in his lovely book on etymological drift,

Semantics Antics,

explains why long ago (as the Mexicans say, “when dogs were tied with sausages”) you wouldn’t have wanted to be nice, smart, or handsome but would rather have been a bully, or silly, or sad, and why you would have wanted to be insulted but not to have too many hobbies.

Nice

originally meant someone who was foolish, ignorant, senseless, or absurd (middle English 1300).

Smart

for the first 300 years of its use meant causing pain, sharp, cutting, or severe, a sense that survives in the idiom

smart as a whip

but is now used differently in “whip smart.”

Handsome

wasn’t complimentary. When coined around 1425, it just meant easily handled; it didn’t have its current positive connotation until 1590.

Bully

originally meant “darling or sweetheart” and is often found in this sense in Shakespeare. For example, in

Henry V,

“I love the lovely bully” wasn’t a confession of masochism.

Silly

in early Middle English meant “happy,” “blissful,” “blessed,” or “fortunate.”

Sad

in Olde Englishe meant “full,” “satiated,” or “satisfied.”

Insult

in the 1500s meant the same as

exult,

which is to “boast,” “brag,” “triumph” in a insolent way.

Exult

still has a related meaning, but

insult

has changed substantially.

Hobbies

in 1375 were ponies, or small horses—a sense that survives in the expression “hobby horse”; it’s via a contraction of this sense that the present-day usage meaning “pastime” developed.

When dogs were tied with sausages

Spanish (Uruguay): very long ago

Words can also be entirely lost in the mists of time. They get relegated to larger and less frequently consulted dictionaries,

*

and finally suffer the ultimate insult of being delisted. Ammon Shea, in his wonderfully entertaining book

Reading the OED,

notes some excellent dying words that could be beneficially resuscitated.

5

My favorite candidate for revival is

gymnologize

. It means “to dispute naked, like an Indian philosopher.” Shea’s book is highly recommended. The following are a small sample of its delights:

- Vocabularian:

one who pays too much attention to words - Unlove:

to cease to love a person - Tardiloquent:

talking slowly - Somnificator:

one who induces sleep in others - Sarcast:

a writer or speaker who is sarcastic

* - Natiform:

buttock-shaped - Mythistory:

a mythologized account of history - Mislove:

to hate, to love in a sinful manner - Lant:

to add urine to ale to make it stronger - Kakistocracy:

government by the worst citizens - Idiorepulsive:

self-repellent - Gulchin:

a little glutton! - Finifugal:

shunning the end of anything - Eumorphous:

well formed - Debag:

to strip the pants from a person; punishment or joke - Bowelless:

lacking mercy - Bedinner:

to treat to dinner - Anonymuncle:

an anonymous, small-time writer

I’ve previously used the thought image of idioms being frozen metaphors. The occurrence of words no longer in use except in certain idioms is a wonderful flea in the amber demonstration of this fossilization. For example, we no longer say

kith, shrift, haw, raring, kilter, fangled, fro, spick, boggle,

and

hither,

though we still say “kith and kin,” “short shrift,” “hem and haw,” “raring to go,” “off-kilter,” “newfangled,” “to and fro,” “spic and span,” “mind-boggling,” and “come hither.” And while we still say

hue, fell,

and

neck,

their petrified

*

meanings in “hue and cry,” “one fell swoop,” and “neck of the woods” aren’t what they seem.

Hue

in this usage has nothing to do with color—it’s from the Latin for a horn; the expression literally means “horn and shouting.”

Fell

meant something terrible—evil, or deadly ferocity (our word felon comes from the same root).

Neck

used to mean a parcel of land.

Okay, enough

bush beating

. Let’s spend some time looking at the use of time in idioms (before their meanings change).

Ever wondered how frequent

once in a blue moon

is? For a Yiddish speaker it’s “a year and a Wednesday.” To a Hindi speaker it’s three years; their equivalent expression is “every six six months.” To an Italian the concept is less precise, but the interval seems much longer: “every death of a pope.” Colombians are less concerned with the rank of the deceased: “each time a bishop dies.” For Americans a

month of Sundays

indicates a very long time. For a Frenchman, “the week with four Thursdays” or “every 36th of the month” is

when hell freezes over.

And for a Spaniard Friday the 13th is nothing to worry about; they fear the unlucky Sunday the 7th.

QUICK/FAST/YOUNG

- Like a poor person’s funeral:

quickly (Spanish, Costa Rica) - A white colt passing over a crevice:

time flies, life is short (Chinese) - Urgent, like eyebrows on fire:

critical, extremely urgent (Chinese) - Are you standing on one leg?:

Are you in a hurry? (Yiddish) - With a monkey’s tooth:

extremely fast (German) - Has eaten little kasha:

is inexperienced (Russian)

SLOW/LATE

- He creeps like a bedbug:

as slow as molasses (Yiddish) - To do the leek:

to hang around waiting (French) - To be slow as hunger:

to be as slow as molasses (Italian) - Angel is passing by:

pause in the conversation (French) - To come late to a place:

to get nervous (Japanese)

LONG/OLD/PAST

- The days of cherries:

the good old days (French) - To smoke once every death of a pope:

once in a blue moon, rarely (Italian)

When snakes wore vests

Spanish: very long ago

- Each time a bishop dies:

once in a blue moon, rarely (Spanish, Colombia) - Older than pinol [toasted corn drink]:

as old as the hills (Spanish, Nicaragua) - To be for light soup and good wine:

to be old (Spanish) - When snakes wore vests:

a long time ago (Spanish, Chile) - When dogs were tied with sausages:

very long ago (Spanish, Uruguay) - In the year of the pear:

a long time ago (Spanish) - Day when the firemen get paid:

when hell freezes over, never (Spanish, Chile) - To be ancient lavender:

to be old hat (German) - Every sixth six months:

once in a blue moon (Hindi) - A year and a Wednesday:

it will take a long, long time (Yiddish) - Every 36th of the month:

once in a blue moon, rarely (French) - When frogs grow hair:

never (Spanish, Latin America)