I'm Not Hanging Noodles on Your Ears and Other Intriguing Idioms From Around the World (15 page)

Read I'm Not Hanging Noodles on Your Ears and Other Intriguing Idioms From Around the World Online

Authors: Jag Bhalla

RICH/LUXURIOUS/GENEROUS

- To make one’s butter:

to make lots of money (French) - To put butter in the spinach:

to improve one’s living standard (French) - To cost the skin on one’s buttocks:

to make a fast buck (French) - To have hay in your boots:

to feather your nest (French) - To have one’s whole hand in the ghee [butter]:

to be wealthy (Hindi) - To have cheerful pockets:

to be wealthy (Spanish, Mexico) - One’s pocket is warm:

wealthy (Japanese) - One’s breast is deep:

generous (Japanese) - To live like God in France:

to live in luxury (German) - To live like a maggot in bacon:

to live in luxury (German) - To live on a large foot:

to live in luxury (German) - To earn oneself a golden nose:

to make a lot of money (German) - To have an elephant swing at the gate:

to live in luxury (Hindi) - To fly pigeons:

to have no cares, live in luxury (Hindi) - A wool sock well stuffed:

a nice nest egg (French) - Chickens do not peck the money:

to roll in money (Russian) - To be stuffed up, to be stuffed with:

to be very wealthy (Yiddish) - A rich man has no need of character:

proverb (Hebrew)

TO SPEND MONEY

- To cost a candy:

expensive (French) - To cost an eye of the face:

expensive (Spanish) - Salty:

pricey, expensive (Spanish, South America) - To throw the house out the window:

to spend lavishly (Spanish) - Scratch the pocket:

spend reluctantly (Spanish) - The pure potato:

cold hard cash (Spanish, Colombia) - Despised metal:

money (Russian)

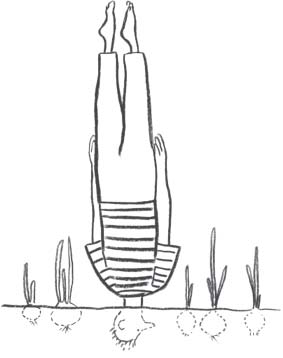

He should grow like an onion with his head in the ground.

Yiddish: go take a hike

FOOD & DRINK

Give it to someone with cheese

M

Y PEOPLES WERE INVOLVED

in a culinary coup d’état in 2001. It was a great year for Anglo-Indian food. Robin Cook, then the British Foreign Secretary, said in a speech that “chicken tikka masala is now a true British national dish, not only because it is the most popular, but because it is a perfect illustration of the way Britain absorbs and adapts external influences. Chicken tikka is an Indian dish. The masala sauce was added to satisfy the desire of British people to have their meat served in gravy.”

1

This momentous event addressed a couple of my food and identity issues. First, Britain isn’t exactly respected for its national food. Non-Brits usually think of fish and chips and perhaps the full British breakfast (complete with black pudding—which is fried pig’s blood sausage). So chicken tikka masala is a big step forward. Second, I’m a great consumer and promoter and provider of Indian food. I particularly enjoy breaking the bread of my ancestors with companions (at events known as Naan Nights). And the culinary influence of my ancestors isn’t limited to Britain—one of Germany’s most popular fast-food dishes is now the curry-wurst (more on Germans and their love of processed meats to follow).

As Robin Cook was pointing out, inclusion-and-fusion is a process often used by the British. It certainly applies to language as well as to food. Henry Hitchings, in his exuberant book

The Secret Life of Words,

estimates that English has added much flavor by gobbling up words from 350 other languages.

2

India has also practiced inclusion-and-fusion. I was a little shocked to discover that dishes we think of as characteristically Indian aren’t entirely so. Curries rely on chilies that were brought to India by the Portuguese. Not a discovery that curried

*

favor with me.

Even the word

Indian

is of European origin. It was in use in England long before it was used in connection with the land of my ancestors. India originally meant any foreign land.

3

Hence it made sense, from a Eurocentric point of view, to speak of an East Indies and a West Indies, and to call the inhabitants of the Americas Indians. England and English are also so called for Eurocentric reasons. The word

England

is derived from the land of the Angles, who were a tribe of early invaders from what is present-day Germany and the northern Netherlands.

Getting back to food and national dishes…

For Italians we immediately think of pasta (though that is thought to have originated in China). Italians have particularly colorful language for their 500-plus varieties. Some of their entertaining translations include the familiar: worms (thin is

vermicelli

and thick is

vermicelloni

), little strings (

spaghetti

), spirals (

fusili;

same root as

fusilier,

or spiral), little tongues (

linguini,

or flattened spaghetti), knots of wood

(gnocchi).

But also the less familiar: little fingers (

ditalini

), little beards (

barbina

), moustaches (

mostaccioli

), little ears (

orecchiette

), half moons (

mezzalune

), pandas (

fantolioni

), butterflies (

farfalle

), infesting weed (

gramigna

), and, finally, the alarming priest chokers or strangled priests (

strozzapreti

)!

For the Japanese we think of sushi, though we often misconstrue that to mean raw fish. It actually refers to the fermented rice that the fish (or vegetables or meat) sits on. The Japanese take that rice very seriously. As Trevor Corson reveals in his delicious book

The Zen of Fish,

it can take a sushi chef in Japan up to two years just to learn how to get the rice right. American sushi chefs can learn

the whole shebang,

rice and all, in 12 weeks. Corson also reveals that sushi is like pasta, in that it probably originated in what is now part of China.

For the Spanish we think of paella and tapas. The word tapas means “lids” or “covers.” Its use in relation to food supposedly derives from the practice of covering sherry glasses in Andalusia with thin slices of bread or meat to keep the flies off. A related recently invented word from The Daily Candy Lexicon is

crapas,

used to describe the terrible finger food served at public relations events.

4

We’ve seen how language can provide a window into various ethnic stomachs. Let’s see what other aspects of food culture idioms can shed light on:

For Germans, we perhaps think of their obsession with processed meats. While English speakers might be living

in the lap of luxury

or living the

life of Riley,

a similarly fortunate and content German prefers to be “living like a maggot in bacon.” Processed meats also feature prominently in their expression for sulking, which is “to play the insulted liver sausage” and for “giving special treatment,” which is “to fry a bologna sausage.” Having given in too much to the temptations of their processed meats, dieting Germans can be described as engaging in the wonderfully graphic “de-baconing.”

Though it is said that man cannot live by bread alone, she can use bread to ensure that she is not always alone. In English

we break bread with

friends (incidentally, that is what the word companion means:

com

(“with”) +

pan

(“bread”) = “bread fellow”). Similarly, social Russians “carry bread and salt” or “meet with bread and salt,” and Arabs simply “take salt with you.” And to further emphasize the perceived benefits of social eating, Arabs have a proverb that says, “An onion shared with a friend tastes like roast lamb.”

Speaking of food, evolutionary psychologists have suggested that the absence of any effective form of refrigeration was critical to our early moral development. Let’s say that you’re an early humanoid hunting and gathering on the African savannah and you strike it lucky: You come across a huge beast and you manage to kill it. It yields far more meat than anyone involved in the hunt or their families can possibly consume. How do you get the most benefit of your excess meat without a fridge? Without anywhere to store it? The smartest of our deep ancestors would have stored their excess meat in the bodies and minds of others (not just their own kin). Provided those benefiting from your largesse could possibly repay your generosity in the future, that was the best thing you could do with excess meat. Groups of early humans who developed stable relationships and practiced this sort of reciprocal altruism were in a better position to prosper and multiply. Some of these adaptive benefits survive in our moral instincts today—even in forms of altruism that aren’t so nakedly reciprocal. Refer, for example, to the earlier quotations from Adam Smith’s first great work,

The Theory of Moral Sentiments

(see Chapter 11). Italians have a great word for gifts with strings attached that translates as “hairy generosity.”

Speaking of food sufficiency, when we eat

to our heart’s content,

Russians like “butter over the heart” and the Japanese more audibly “beat a belly drum.” Meanwhile, “eating twice a day” is enough for Hindi speakers. For motivation, we can use a

carrot-and-stick

approach, but Germans express their preference for less nutritious incentives, requiring “sugar bread and whip.” When we think that we are the

center of the universe

or the

bee’s knees,

an equally egocentric Spaniard thinks she “is the hole in the center of the cake.” And where we seek to

have our cake and eat it too,

the French prefer to “save the goat and the cabbage.” Saving by “reheating the cabbage” for an Italian means dis-charmingly to attempt to revive a lapsed love affair. For the Dutch, to be enjoying good food is both sacred and grossly sacrilegious; it’s like “an angel urinating on your tongue.”

Along the lines of alcoholic associations, we think of Germany with beer, France with fine wines, Japan for sake, and Russia for vodka, any of which can lead to getting drunk. An inebriated Frenchman would be “buttered,” a Spaniard “breast fed,” a German could be either simply “blue,” or perhaps “have a monkey sit on him.” A not-so-great Dane might “have carpenters,” implying that they were banging in his head. Italian idioms attest to the strength of the national relationship with coffee: Espresso is a “shrunken coffee,” and liquor is “corrected coffee.” As to the Italian understanding of corrected expectations, there is a proverb that warns, “You can’t have a full barrel and a drunk wife.”

Let’s see what other enticing morsels of culinary culture are revealed by international idioms involving food.

COFFEE & TEA

- Shrunken coffee:

very strong espresso (Italian) - To do a java:

to have a party (French) - To brew the dirt from someone’s fingernails and drink it:

to learn a bitter lesson from someone (Japanese) - A glass of warmth:

tea (Yiddish) - To make tea cloudy:

to dither (Japanese) - One’s navel boils tea:

laughable (Japanese) - To bang on the tea kettle:

long-winded, annoying talk (Yiddish) - Don’t stir the tea with your penis! (ouch):

Don’t mess things up (Russian)

ALCOHOL

- Good with the left hand:

to be a drinker (Japanese) - To have a glass up one’s nose:

to have one too many (French) - To have a flag:

to reek of alcohol (German) - To buy oneself a monkey:

to get drunk (German) - Full of stars and hail:

very drunk (German) - To be buttered:

to be drunk (French) - To be breast-fed:

to be drunk (Spanish, Argentina) - To be blue:

to be drunk (German) - To have the canal full:

to be drunk (German) - To have a monkey sit on one:

to be drunk (German) - To go along with one’s cheek on the sidewalk:

to be drunk (Spanish, Mexico)

To drown the mouse

Spanish: to take a drink to stave off a hangover

- To have a guava tree:

to have a hangover (Spanish, Colombia) - To have a fat head:

to have a hangover (German) - The sound of cats mating:

to have a hangover (German) - To ferment one’s wine:

to sleep off a hangover (French) - To have a mouth made of wood:

to have a hangover (French) - To drown the mouse:

to take a drink to stave off a hangover (Spanish) - A cask of wine has more miracles than a church full of saints:

proverb (Italy)

HUNGRY

- Hungry like Virgin Mary:

starving (Italian) - To go with the long tooth:

dying of hunger (Spanish, Chile) - Bring the gut tied:

faint with hunger (Spanish, Mexico) - To be barking:

to be hungry (Spanish, Colombia) - Cleverer than hunger:

quick-witted (Spanish)

EATING & OVEREATING

- Door hinge gobbler:

glutton (Spanish, Mexico) - To ring one’s bell:

to feed one’s face (French) - A good fork:

a hearty eater (Italian) - To do the little shoe:

to clean your plate (Italian) - The one of shame:

the last food on a plate that no one dares take (Spanish) - To beat a belly drum:

to eat heartily (Japanese) - To eat twice a day:

to have enough to eat (Hindi) - To undo twists in the entrails:

to eat one’s fill after starving (Hindi) - Stomach fire:

indigestion (Hindi) - I already killed what was killing me:

I’m full (Spanish, Colombia)

SALT

- To be salted:

to be unlucky (Spanish, Mexico) - Salty:

expensive (Spanish, South America) - With good salt and plums:

fortunately (Japanese) - Not allow salt in the soup:

grudgingly (German) - One eating salt:

servant or dependent (Hindi) - Faithlessness to one’s salt:

ingratitude to a benefactor (Hindi) - We’ll take salt with you:

acceptance of invitation to share a meal (Arabic) - To be like bread without salt:

bland, unattractive (Spanish, El Salvador) - To carry on like bread and salt:

to be good friends (Russian) - Meet with bread and salt:

warm welcome (Russian) - Like salt in flour:

plunged into difficulties (Hindi) - He is like salt:

someone who is into everything (Arabic) - A salty face:

a sullen face (Japanese) - To handle with salted hands:

to raise with tender care (Japanese) - To not have salt on the crown of the head:

not very bright (Spanish) - To put salt in the

kheer

[rice pudding]:

to ruin (Hindi)