Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks & Fraud in Financial Reports, 3rd Edition (31 page)

Authors: Howard Schilit,Jeremy Perler

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Accounting & Finance, #Nonfiction, #Reference, #Mathematics, #Management

Cash Flow from Operations: The Favored Son

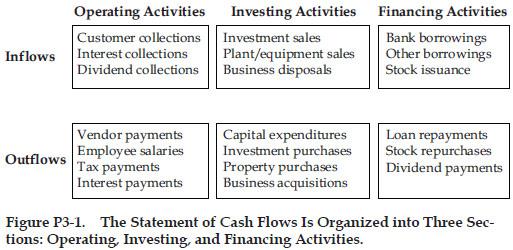

Before diving into these Cash Flow Shenanigans, it is important to understand the basic structure of the Statement of Cash Flows. The SCF shows how a company’s cash balance changed over the period. It presents all inflows and outflows of cash, reconciling the beginning to the ending balance. All cash movements can be grouped into one of three categories: Operating, Investing, and Financing activities. Figure P3-1 illustrates the typical inflows and outflows within each section of the SCF.

Investors do not consider the three sections of the Statement of Cash Flows equally important. Rather, they regard the Operating section as the “favored son” because it presents cash generated from a company’s actual business operations (i.e., cash flow from operations). Many investors are less concerned with a company’s investments or capital structure, and some even go to the extreme and completely ignore the other sections. After all, the Operating section should fully convey a company’s operating activities, right?

Well, not really. Companies can exert a great deal of discretion when presenting cash flows. Many popular Cash Flow Shenanigans can be labeled

intraperiod geography games

— a liberal company interpretation of “what goes where” on the Statement of Cash Flows. For example, should an outflow be shown in the Operating or the Investing section? Clearly, management’s answer would have a profound effect on the reported CFFO and on an investor’s assessment of the company’s performance. Other shenanigans involve subjective management decisions that influence the timing of cash flows in order to portray an overly rosy economic picture.

Robin Hood Tricks

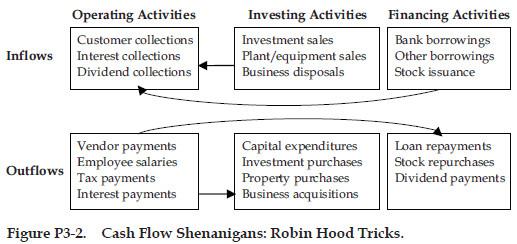

Think of these intraperiod geography games as “Robin Hood” tricks: stealing from the rich section of the Statement of Cash Flows and giving to the poor one. In most cases, the “poor” section will be the Operating section, which investors follow much more closely, and the “rich” sections will be the Investing and Financing sections, which investors tend to ignore.

As you will see, these Robin Hood tricks are actually quite simple and more common than you might imagine. It is not that difficult for companies to concoct a reason to move the good stuff (cash inflows) to the most important Operating section, and send the bad stuff (cash outflows) to the less important Investing and Financing sections. Figure P3-2 illustrates some of these tricks, such as improperly moving inflows that really came from bank borrowings to the Operating section or shifting those unwanted outflows out of Operating and labeling them capital expenditures.

Where Is the Sheriff of Nottingham?

Just as the Sheriff of Nottingham could not prevent Robin Hood from stealing from the rich and giving to the poor, the current accounting rules often seem inadequate to prevent companies from engaging in such cash flow shenanigans. This is because the rule makers failed to adequately address many key issues when they wrote the accounting rules for the Statement of Cash Flows. Indeed, when addressing “what goes where” on the Statement of Cash Flows, the accounting rules are quite vague, providing management with a great deal of discretion.

In fact, occasionally the accounting rules can be considered as “accomplices” in the Robin Hood tricks because, as applied, in some cases they fail to capture the true economics of transactions. As a result, even when companies follow the rules, they may still present a CFFO figure that measures the organic growth of the business poorly. Of course, companies that follow the rules should not be accused of chicanery. Nonetheless, playing by the rules does not always result in financial reporting that accurately reflects the underlying economic reality.

Good News and Bad News (but Mostly Good News)

Now it’s time for some good news and some bad news. The

bad news

is that many techniques exist that allow companies to portray misleading cash flow. Moreover, many aspects of the rules surrounding the Statement of Cash Flows create confusion about the sustainability of the CFFO reported to investors.

However, the

good news

is that you realize this—indeed, you are reading this book. You are about to learn how to detect these tricks quickly and gain the knowledge and tools necessary to successfully go toe-to-toe with companies whose management attempts to mislead you with Cash Flow Shenanigans.

The next four chapters offer a guided tour of four Cash Flow Shenanigans, including techniques used by management to shift undesirable outflows away from the Operating section and push desirable inflows into that section. Naturally, we share our secrets on how to detect signs of these shenanigans. Chapter 10 starts off with shifting the cherished inflows from financing arrangements to the Operating section.

10 – Cash Flow Shenanigan No. 1: Shifting Financing Cash Inflows to the Operating Section

Arnold Schwarzenegger and Danny DeVito were an unlikely pair in the 1988 hit comedy

Twins

. They were born in a genetics lab as the result of a secret experiment to create the perfect child. Doctors manipulated the fertility process to funnel all of the desirable traits to one child while sending the “genetic trash” to the other. They were able to create an intelligent Adonis (Schwarzenegger), but in order to do so, the doctors also had to create his gnomish, conniving twin brother (DeVito).

That very same year, new cash flow reporting standards (SFAS 95) took effect, officially formalizing the Statement of Cash Flows and its three sections (Operating, Investing, and Financing). It seems that some corporate executives were reviewing the new rules at the same time that they were watching the fertility manipulation in

Twins

. This may be where they got the crazy idea of manipulating the Statement of Cash Flows by sending all of the desirable cash inflows to the most important section (Operating) and all of the unwanted cash outflows to the other sections (Investing and Financing).

In recent years, many companies have seemingly been operating their own

Twins

genetics labs. But rather than attempting to create the perfect child, they are attempting to create the perfect Statement of Cash Flows. In this chapter, we expose one of the most important secret procedures being performed inside those labs: shifting the desirable inflows from a financing transaction to the Operating section.

Techniques to Shift Financing Cash Inflows to the Operating Section

1. Recording Bogus CFFO from a Normal Bank Borrowing

2. Boosting CFFO by Selling Receivables Before the Collection Date

3. Inflating CFFO by Faking the Sale of Receivables

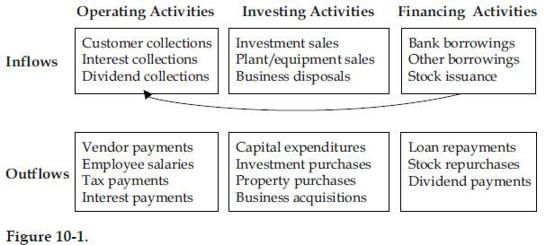

These three techniques all represent ways in which companies inflate cash flow from operations (CFFO) by shifting net cash inflows from financing arrangements to the Operating section, as illustrated in our handy cash flow map in Figure 10-1.

1. Recording Bogus CFFO from a Normal Bank Borrowing

Sham Sales of Inventory to a Bank

At the end of 2000, Delphi Corporation found itself in a bind. It had been spun out from General Motors (GM) a year earlier, and management was intent on showing the company to be a strong and viable stand-alone operation. However, despite management’s ambitions, all was not well at the auto parts supplier. Since the spinoff, Delphi had cooked up many schemes to inflate its results. The auto industry was reeling, and the economy was getting worse.

Delphi’s operations continued to deteriorate in the fourth quarter of 2000, and the company was facing the prospect of having to tell investors that cash flow from operations had turned severely negative for the quarter. This would have been a devastating blow, as Delphi often highlighted its cash flow in the headline of its earnings releases as a key indicator of the company’s performance and its (purported) strength.

So, already knee-deep in lies, Delphi concocted another scheme to save the quarter. In the last weeks of December 2000, Delphi went to its bank (Bank One) and offered to sell it $200 million in precious metals inventory. Not surprisingly, Bank One had no interest in buying inventory. Remember, we are talking about a bank, not an auto parts manufacturer. Delphi understood this and crafted the agreement in such a way that Bank One would be able to “sell” the inventory back to Delphi a few weeks later (after year-end). In exchange for the bank’s “ownership” of the inventory for a few weeks, Delphi would buy it back at a small premium to the original sale price.

Let’s step back and think about what really happened here. The economics of this transaction should be clear to you: Delphi took out a short-term loan from Bank One. As is the case with many bank loans, Bank One required Delphi to put up collateral (in this case, the precious metals inventory) that could be seized in case Delphi decided not to pay back the loan. Delphi should have recorded the $200 million received from Bank One as a borrowing (an increase in cash flow from financing activities). As a plain vanilla loan, this transaction should have increased cash and a liability (loan payable) on Delphi’s Balance Sheet. Clearly, borrowing and later repaying the loan produces no revenue.

Rather than recording the transaction in a manner consistent with the economics and intent of the parties, as a loan, Delphi brazenly recorded it as the sale of $200 million in inventory. In so doing, Delphi inflated revenue and earnings, as discussed in EM Shenanigan No. 2. Moreover, it also overstated CFFO by the $200 million that Delphi claimed to have received in exchange for the “sale” of inventory. As shown in Table 10-1, without this $200 million, Delphi would have recorded only $68 million in CFFO for the whole year (rather than the $268 million reported), including a dismal negative $158 million in the fourth quarter.

Remember That Bogus Revenue May Also Mean Bogus CFFO

. In EM Shenanigan No. 2, we discussed techniques that companies use to record bogus revenue, including engaging in transactions that lack economic substance or that lack a reasonable arm’s-length process. Some investors become so disillusioned when they read about bogus revenue and other earnings manipulation tricks that they decide to completely ignore accrual-based numbers and, instead, blindly rely exclusively on the Statement of Cash Flows. We consider that decision unwise. Investors should understand that

bogus revenue might also signal bogus CFFO.

This was clearly the case in the Delphi example discussed here, as well as in many other so-called boomerang transactions. Thus, as a rule, signs of bogus revenue may