Crossing the Borders of Time (25 page)

Attempting to help Gray’s population survive beneath the yoke of oppression, André Fick and the mayor needed to run a few stealthy steps ahead of the Germans. With a golden rule of “discretion and silence,” Fick told me, they shielded the town from cruel Nazi excesses, using deceptions and lies to ward off reprisals and rescue many who would have been victims. They intervened to help the Graylois and, even as they manipulated to gain the trust of the Germans, the two Alsatian Marists subtly schemed right under their noses.

“We waged war against them,” André recalled on the day that I met him. “Not with guns and bayonets, but a war all the same, a war that we waged in writing and meetings.” And yet there were those, he sadly confided, who, regarding him as well as the mayor as tools of the Germans, maligned them in whispers as collaborators who helped to enforce the victors’ demands. “The people of Gray saw me go to the

Kommandantur

every day, and they viewed that as shady. They saw me go with my documents, and they said, ‘He’s a collaborator.’ That’s the normal reaction. My actions, like those of Monsieur Fimbel, were not always well understood by the population. They saw us go every day, but it was

not

to lick the boots of the Germans, but to press for favors for the people of Gray.”

All through the summer and fall of 1940, Joseph Fimbel continued to visit with Sigmar, his old Jewish friend. For warmth, as autumn set in, they sat at the kitchen table near the potbellied stove retrieved from Mulhouse, Alice doing her best with limited rations to offer the mayor simple refreshment. Even before the outbreak of fighting the previous winter, coupons dispensed at the

mairie

had fixed the amount of bread, meat, sugar, wine, flour, fats, soap, and charcoal allotted townspeople, based on their age and the work they performed. Once the Germans took over, claiming most of the food for themselves or for export to feed their country and troops, they held the Graylois to a diet of approximately one thousand six hundred calories a day, a limit they later cut almost in half. There were also restrictions on purchasing bicycle tires, textiles, and shoes, which led to new styles with soles made of wood. An informal bartering system quickly arose, with cigarettes readily serving as money.

In that first autumn of occupation, Gray’s agricultural setting provided residents with more copious food than those who lived in cities could find. There were fruits and vegetables in the marketplace on the broad cobblestoned plaza before town hall, and butter and eggs often available at nearby farms. And so, on the evenings the mayor came by, Alice was pleased to see him cheer up her husband and unstintingly served him her kitchen’s best, along with a cup of hot bouillon, a small glass of wine, or weak so-called coffee brewed out of chicory.

The two friends still occasionally sparred in religious debate, but increasingly, current events led to political worries, and one evening the mayor arrived to find Sigmar engulfed by hurt feelings that focused their talk on the tactical problems involved in escape. That afternoon’s mail had brought a postcard from Marie’s son Edy, writing from relative safety in Switzerland, where, as a military man seeking asylum, he’d been interned since France fell. What appeared on the surface as a genial family message from him actually bore oblique instructions that caught Sigmar’s eye and on closer inspection stirred his resentment.

“

This would be a nice time to pay a visit to Mimi. Bring Bella

,” Edy had guardedly written his mother. Postcards were the only mail the Germans allowed the Graylois to receive from outside the Occupied Zone, and unless their subject was tightly focused on family matters, censors destroyed them. But between Edy’s lines, Sigmar read a clear warning, one he found troubling not for its message, but rather for what it left out. Take Bella and maneuver

now

to get out of Gray and the Occupied Zone and into the so-called Free Zone by going “to visit” Mimi in Lyon, Edy advised. Of Sigmar and Alice, of Janine and Trudi, Edy wrote not a word. No, the nephew Sigmar loved like a son had no word for them, nothing, despite all Sigmar had done to shield Edy’s mother and Bella since fleeing Mulhouse the previous year.

Sigmar’s nephew Edmond “Edy” Cahen, a captain in the French Army, was held in Switzerland under terms of asylum after the Germans conquered France

.

“

Amène Bella. Amène Bella

,” Sigmar muttered under his breath, indignant that Edy would instruct Marie to bring the housekeeper while blithely ignoring the rest of the family. Shame at reading his sister’s mail without her permission, albeit a postcard, prevented Sigmar from raising the issue with her. The unexpectedness of his nephew’s counsel also caught him off guard. Prohibited as a Jew from owning a radio and relying for news on the local newspaper—with

La Presse Grayloise

now heavily censored by the German

Kommandantur

—it was hard to know how the war was progressing. Carefully molding public opinion, the paper prominently featured reports of German triumphs in battle and warned that French “terrorists” faced execution.

So, Sigmar wondered, was it better to sit tight in Gray, where his friendship with Fimbel offered protection? Or would they be safer, as Edy suggested, in the unoccupied sector controlled by Pétain, a man who could not be expected to stick out his neck to save foreign-born Jews who ran there to hide? Even assuming they might be safer in Lyon, could they obtain transit papers to allow them to leave? Where would they live? And what about Norbert? They had heard nothing from him since he left with the Legion. Now that France was out of the war, what if his son made his way back to Gray only to find the family gone?

He decided to broach these questions to Fimbel when the mayor came to see him that evening, but his friend began by relaying terrible news. As part of a broad-scale roundup of Jews in Baden and other German border regions, the Nazis had deported to the French camp of Gurs every last Jew they could still find in Freiburg. Sigmar sat stunned. Fräulein Ellenbogen, Frau Loewy, all their friends still in the city when he’d fled with his family from Freiburg to Mulhouse—had they escaped, or had they been seized? His own complacency, remaining this long in occupied Gray, now seemed insane. Survival meant evading the Germans, not living as literal neighbors with the

Kommandantur

headquartered in the town’s former Chamber of Commerce just two doors away from the family’s apartment. With new urgency, Sigmar laid out his dilemma to Fimbel, who described in sobering detail the hurdles involved in crossing the border to the so-called Free Zone.

The border was virtually sealed, Fimbel said, unless one acquired a safe-conduct pass, which required approval from the German

Kommandantur

. With demand rising daily, desperate applicants swamped town hall with requests for permission to cross the Demarcation Line between the two zones. Once processed by the French, all paperwork went to the German command. But the Germans systematically rejected any requests from Jews, and even non-Jews had to prove compelling reasons in order to gain the passes they needed: sick or dying relatives, children or parents in need of help, or faltering businesses that demanded attention. The postmaster, Malou’s father Monsieur Gieselbrecht, was secretly signing false papers that testified to telephone calls received at the

Poste

from outside the Occupied Zone, urgently summoning people home. As to fellow Alsatians who now risked being forced to fight in the German Army, Monsieur Fimbel was providing false identity papers to help them slip out of sight before they were drafted.

According to André Fick, among Frenchmen from Alsace-Lorraine whom the Germans would eventually draft to fight for the Reich in bloody Eastern Front battles, many deserters fled to Gray, having heard that the Alsatian-born mayor could arrange their “rebirth.” He gave them new names and work as laborers assigned to restore the war-torn farmland around the city. Trusted

passeurs

smuggled some to safety in Switzerland or over the line to the Unoccupied Zone, and later helped others escape to North Africa to join what was left of the Free French Army. Mayor Fimbel hid some escapees in trucks that carried supplies to larger towns like Dijon, where he reluctantly left them to plot their next moves, and he personally drove others up to the border, where a well-placed bribe of cognac, champagne, tobacco, or coffee could help raise the barriers. When the Nazis started hunting down Jews, the Marist mayor would help them flee, too, saving scores by furnishing them with transit papers, by warning targets of impending arrest, and by hiding others in the secluded countryside homes of his former students.

For his clandestine efforts, Joseph Fimbel depended upon a close, loyal team, and he soon suggested to Sigmar that Janine might come to work for him at the

mairie

. Her fluency in German and French, he said, would be valuable in helping his office cope with the flood of requests for safe-conduct passes. She could not be officially paid, but the job would offer unspoken potential. From a desk in town hall, Janine would deal with the many who frantically begged for papers to cross out of the zone and would help them fill out their forms in ways that bolstered their reasons to leave. Every few days, prepared to face questions, she would be sent with a stack of requests to the

Kommandant

, who examined these papers and signed the ones he chose to approve.

In retrospect, it is hard to believe that neither the mayor nor Sigmar addressed the risk of such regular contact with the German command, and that Janine herself, at just seventeen, would brave the perils of serving as an emissary between the

mairie

and the

Kommandantur

. Yet she leaped at the chance with enthusiasm and an unfamiliar sense of importance. She would later observe that the job in which she was so out of place that it put her in danger—a German Jewish refugee working in daily contact with a

Wehrmacht

commander who assumed she was French—made her feel, for the first time since leaving Roland, that her days had meaning and that she belonged. Applicants arrived at her desk with fear of rejection etched on their faces, and she tried to assist them. In front of the Germans, she did not let on that she was Jewish

or

German, and granted license to pretend to be French, she clung to that guise from that moment forward.

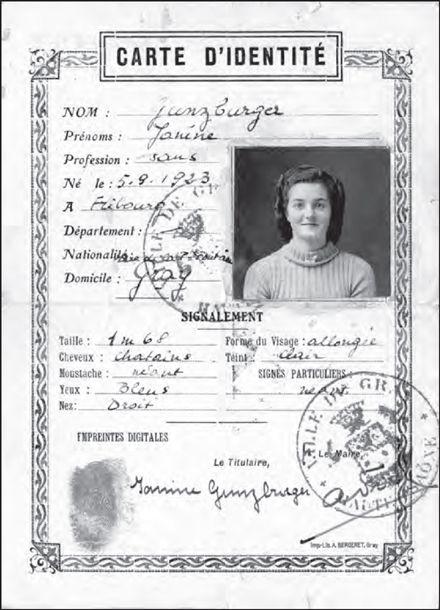

A new identity card, signed and stamped with the seal of the city and made out for her by André Fick, her supervisor, gives touching proof of his zeal to protect her. All the requisite information is duly recorded: her real name, along with the blue whorl of a fingerprint and a picture in which she appears completely untroubled, full cheeked, wide-eyed, fresh, and smiling, in a ribbed turtleneck sweater with a pin at her throat:

Janine’s new identity card, prepared by André Fick, attempted to conceal her German nationality

.

SIZE:

1

meter 68

H

AIR:

chestnut

M

USTACHE:

none

E

YES:

blue

N

OSE:

straight

F

ACE

S

HAPE:

oblong

S

KIN

C

OLOR:

light

D

ISTINGUISHING

M

ARKS:

none visible