Crossing the Borders of Time (20 page)

The Italians had jumped into the war only four days before, with France’s defeat already in sight. They descended on Gray at the

Luftwaffe

’s orders—like heralds for their more powerful allies—bombing the normally busy quai Mavia on the left bank of the Saône, the gas company, and the perimeter of Gray’s railroad station, where trains evacuating equipment and troops from the Maginot Line monopolized tracks and prevented departures. Frantic refugees and bands of disorganized soldiers jammed the station as they clamored for trains, and a Red Cross canteen strained to feed them with meager resources.

The next morning, with German troops moving on Gray from across the river, leaving a trail of fire and dead civilians and soldiers behind them, French Army engineers set dynamite to blow out three bridges over the Saône, hoping to thwart the German offensive. In the early afternoon, three great explosions rocked the small city as its bridges went flying, cutting off traffic over the Saône and temporarily halting the flow of electricity, water, and gas.

The battle that followed that day began with two uneven forces fixing their sights on each other over the river. A ragtag assortment of defending French soldiers—outmanned, outgunned, and sadly outfoxed—was forced to retreat only hours after the fighting had started. Crossing the Saône on their own inflatable dinghies, in boats they found moored along the right bank, or by land over one small bridge that had not been destroyed, the Germans advanced in relentless assault. Their powerful tanks and artillery bombarded Gray’s empty streets, and their bombers, streaking in waves overhead, torched the crest of the town as well as the level sections close to the river. Buildings burst into flame, and by late afternoon the hellfire devouring their beloved church’s bell tower seared the soul of the small Catholic city. A French captain would later describe the dirge of the church bells—partially melting as they dropped from the tower in a burning hail of stones and debris—tolling their last, a death knell that mourned the town’s forced surrender.

Within the hour, Nazi storm troopers seized control of the town. Later that evening a German officer strode into Monsieur Gieselbrecht’s post office to demand that the mayor be summoned to the foot of the damaged Stone Bridge to receive orders. While the citizenry fled, the mayor had stayed on in Gray to assist its defenses. But the imperious German commander was not disposed to negotiate terms with the French official who arrived at the bridge—tall and patrician, wearing a suit and a bow tie.

“

Sénateur-Maire Moïse Lévy

.” The mayor introduced himself with the slightest of nods.

“

Sie

…

Jude?

” You … a Jew? the German lieutenant colonel reportedly sputtered at hearing the name, amazement leaving him virtually speechless, which turned out not to matter, as he and the mayor could barely understand one another. The officer fished for a monocle that he fixed in his eye, then studied the elderly Frenchman as if searching for something beside the Old Testament name that might betray his unsuitable lineage. Unflinching, Mayor Lévy stood erect for inspection with a full head of close-cropped snowy-white hair and a curling mustache with a smile of its own. “

Juif? Oui!

” he replied, no sign of fear on his dignified features, as witnesses later described that encounter.

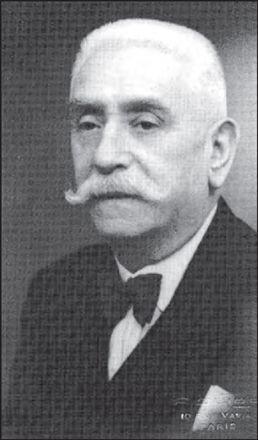

Instead, Gray’s Jewish mayor, then seventy-seven, was the first man in town to show open resistance to German orders of occupation, orders that began by imposing a curfew and quickly moved on to restricting resources. The Germans wanted all the French wounded removed from the hospital to make way for their own injured soldiers. Then they commanded the firefighters to stop using water to extinguish the flames still claiming buildings all over the city. Water was strictly reserved for the Germans, for their men in the hospital or installed in town barracks. They refused to yield to entreaties or accept proof that the local water supply could amply fulfill everyone’s needs while also putting out fires now rapidly spreading. As a result, personal consequences be damned, Mayor Lévy assumed authority for saving the town by overturning directives given his firemen. Elected as mayor first in 1912, after twenty years as town councillor, Lévy had won city hall many times over and counted on having his instructions obeyed.

Gray’s longtime Jewish mayor, Moïse Lévy, was also a senator in the National Assembly

.

(photo credit 8.1)

According to André Fick—a Mulhouse-born teacher who resettled in Gray to serve as Monsieur Fimbel’s assistant, became a good friend to Janine, and later wrote about life there under the Germans—the mayor inscribed his own edict on the back of a business card he gave to the firemen: “

Senator-Mayor Moïse Lévy gives the order, under his personal responsibility, to continue fighting the fires

.” Thus for the next ten days and nights, as his word somehow prevailed, the town battled the blazes that threatened buildings and homes, especially as French-British bombing missions continued to target the German invaders after Gray was defeated.

On city halls all over the region, the black swastika was hoisted in place of the tricolor as the Germans swept south and west from Sedan and fanned out across France, their troops swarming like locusts from Switzerland’s border toward the Atlantic. On June 15, after little more than one day of fighting, the Germans succeeded in seizing Verdun with losses of fewer than two hundred men, a goal they had failed to achieve in ten months of fighting in 1916, despite a death toll eighty times higher. President Roosevelt rejected an urgent plea for assistance, and the British failed to provide sufficient support to persuade the French of their wholehearted commitment as allies. Less than three months before, Great Britain and France had agreed that neither side would make a separate peace with the Germans, but now the situation had changed. Overwhelmed, France capitulated.

On June 17, in a radio broadcast from the French government’s Bordeaux encampment, Marshal Pétain, the beloved eighty-four-year-old hero of Verdun in the previous war, announced that he was replacing Prime Minister Reynaud, who had resigned. Pétain, who blamed the British for France’s collapse, announced he would seek an end to the fighting through an armistice to be negotiated in “a spirit of honor.” The next day, however, Brigadier General Charles de Gaulle, having escaped to London, broadcast his own appeal to the French to take heart and pursue the fight against Hitler. He said he was ready to start assembling an army.

“France has lost a battle, but France has not lost the war!” De Gaulle exhorted the French to stand firm with the forces of freedom. “Has the last word been said? Must hope disappear? Is defeat final? No!” This call to arms prompted Pétain to denounce as cowards those who had fled avoiding surrender. He arranged to have a military court try the rebellious de Gaulle in absentia and that August, with de Gaulle still safely in London, condemn him to death. As for Reynaud, Pétain had him arrested, and he was held prisoner in Germany until after the war.

While the governments of The Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg opted for political exile after their armies surrendered rather than do business with Hitler, Pétain welcomed the idea of peace talks as a means of ending the war and resuming a national life that was more or less normal. The losses of battle incurred in only six weeks already weighed heavy: a toll of ninety thousand French dead, two hundred thousand injured, and nearly two million prisoners of war.

But the terms of armistice signed on June 22 were not up for discussion as Pétain had suggested. Rather, they were handed down as a diktat from Hitler himself at a meeting elaborately staged in the same railcar in the forest of Compiègne where the Treaty of Versailles sealed Germany’s ignominious defeat in World War I. Worse, the armistice purposely mirrored in significant ways the punishments that the earlier treaty imposed on the Germans. Now it was the Germans’ turn to demand the French Army be cut to a maximum force of one hundred thousand, and they strangled the French economy in a tightening noose of reparations that amounted to 60 percent of its income. But harshest of all were the conditions set forth for occupation, which provided for Germany to rule the rich northern two-thirds of the French mainland and Pétain’s government to retain limited control of the southern third only. The occupied north gave the Germans Paris, the coastlines along the Atlantic as well as the Channel, access to Spain, and the vast majority of France’s population, industry, food, and resources.

The border between the Occupied and the so-called Free Zone (later changed to the more ominous Unoccupied Zone) would be controlled like one between two different countries, requiring special German permission for the French to cross over the line from one to the other. The Reich recaptured Alsace and Lorraine, and Hitler outlined a so-called Reserved Zone (including Gray) that he slated for annexation sometime in the future, with an extra presence of Germans in charge from the start. In an effort to strip the people of Alsace and Lorraine of their French self-identification, even wearing berets was forbidden. The French language there was banned in churches, in schools, and in commerce, and French names of people and places were forced into German.

In Mulhouse, the fanciful pink

mairie

now became the

Bürgermeisteramt

, as did city halls all over the region, while the conquering Germans also changed the names of main thoroughfares to honor the Führer. This they would do all over the country. But where else could the name change have proved so mordantly witty by virtue of being so unwittingly apt, when new signs for the Adolf-Hitler-Strasse were posted along the rue du Sauvage, the Street of the Savage?

During the next few years, young men and women of Alsace and Lorraine would be required to join the Reich Labor Service, their boys pressed into the Hitler Youth corps, and their men drafted to fight for the Germans. French prisoners of war would be held until permanent peace was established, which ultimately led to three-quarters of the nearly two million French prisoners being kept by the Reich through five years of war. The armistice further required the French to hand over all anti-Nazi German refugees living in France, which obviously had dire implications for the Jews who had fled there, escaping from Hitler.

New attacks linked Jews with Communists and Freemasons as the combined historical cause of most of the miseries inflicted on France. Before long, newspapers and propaganda depicting Jews as thieves and rats began calling for the French government to suppress the “vermin” who, for their own greedy reasons, had pushed the nation into the war.

It was hardly a jailbreak, but Sigmar escaped from the Fort de la Bonnelle in Langres as the German Army closed in and his French guards—morally queasy about leaving inmates locked up while they themselves ran away—opened the gates of the dungeon and advised all their captives to do what they could to save their own necks. Together with the other Günzburger from Gray, with whom he’d grown friendly, Sigmar fled over a footbridge of logs that spanned the moat encircling the fortress, took to the woods, and wound through the fighting in an effort to travel back to his family. Not having witnessed the hysterical panic that drove most of the French to flee as far as they could from the Germans as they advanced, he assumed he would find the women where he had left them. Now, as the fighting raged around the two German Jews with the same name, and they struggled to stay out of sight while sneaking southeast toward Gray, their fears grew with every step. To be caught by the French might mean being mistaken for German spies and, under pressure of battle, could result in their being shot on the spot. To be captured by Germans certainly augured no better result.