Crossing the Borders of Time (21 page)

The guardhouse of the nineteenth-century Fort de la Bonnelle in Langres, where Sigmar was held under suspicion of being a spy for the Germans

(photo credit 8.2)

Without any money and no place to sleep, they were tired, dirty, and terribly hungry, as they traced the German invaders’ scarred and smoking path to the Saône. But relief at reaching the water turned to despair when they discovered the bridges to Gray destroyed. From one severed span to the next, the two men followed the river and scrambled down the slippery banks. They were weighing the risks of swimming across when they found a battered old rowboat tied to the trunk of a willow, half hidden in the tall river grass, minus its oars. Together—more or less in cahoots, after all, as the police had suggested long weeks before—they dragged the old vessel into the water and, ignoring the soft black stew of leaves coating the bottom, they got on their knees to try to paddle the boat with their hands.

Without oars, of course, it was challenging to keep it moving ahead. Their knees, shoulders, and back muscles ached as they desperately stretched to pull through the currents. Aiming to land at the green slope of a picnic spot on the opposite shore known as “the beach” to the locals of Gray, they labored for hours. Drawing closer, they could not fail to notice the absence of Notre-Dame’s bell tower, with its three-tiered crown and watchful French cock. Horrified by the hole in the skyline, both men stopped paddling. Their puckered fingers rested on the rough, splintered gunwales, while the wind gently rocked them. Though the day was warm, they shivered at the sight of smoke that curled like an Indian signal from the rubble of buildings that lay flattened and smoldering. Sigmar’s apartment on the avenue Victor Hugo was frighteningly close to the ruins of the church. He felt old and exhausted, not ready to deal with what he might learn. How he wished he could sit there, peacefully drifting as the sun set on the darkening river and fires licked the night orange.

In the time that Sigmar spent locked up in Langres, his friend Joseph Fimbel had become Gray’s man of the hour. He had risked his life atop ladders, joining the firemen in battling blazes. He stood beside Mayor Lévy at the cemetery where the local priest led combined funeral rites for a score of men, women, and children killed in the battle and bombing. And with his perfect knowledge of German, he was named by Mayor Lévy commissioner in charge of relations with the German

Kommandantur

as part of a special city committee to establish order under the Occupation. Among their first problems was feeding the people. The Germans issued a punishing ruling that barred millers from delivering flour to bakers, ordering them to use only the flour previously stored by the French military. That flour, however, now reeked of petrol that the French Army had poured over its own stocks before the invasion to ruin it in case the enemy seized it. The resulting baked goods were rancid and seemed to the French—tied to the land through their bread—to epitomize all the privations of war.

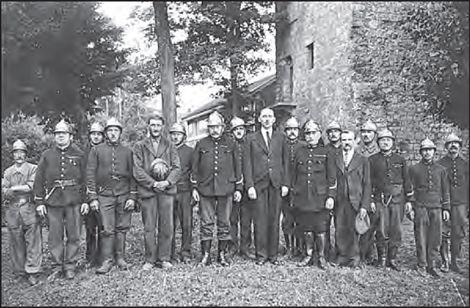

Joseph Fimbel (center) assisted the firefighters after bombing raids set Gray aflame

.

(photo credit 8.3)

“Until these supplies are used up, no other bread will be delivered to the population,” the German authorities warned. They also directed that bakers wait twenty-four hours after baking bread before selling it, which meant the baguettes turned stale and dry before reaching the table. For the Graylois, this bread would linger forever on memory’s palate with the foul aftertaste of humiliation.

Life was increasingly governed by new sets of rules, some imposed by the Germans directly, others sent down from the French prefect of the Haute-Saône to regional mayors. Cafés were to be open to civilians only between eleven and one and between five and nine in the evening; driving was forbidden between ten in the evening and five in the morning; traveling by car

or

bicycle required authorization from the nearest military headquarters or

Kommandantur

; all firearms were to be surrendered at town hall; and all publications, including posters, were to be submitted to the German authorities for review and approval before being printed.

The front page of a censored edition of

La Presse Grayloise

sent the people a message to bear up under a grim situation that they had, in large measure, brought on themselves. The same theme was drummed into France as a whole through the censored newspapers that spread the will of the Germans, thinly camouflaged as objective reporting.

“Beloved people: one word, a single directive. Work. The French people want to work to repair past errors committed under the guidance of its bad shepherds,”

Paris Soir

said on June 24, as in following days it advocated faith in Pétain, obedience to German commands, and strict economy in every household. News photographs showed clean-cut German soldiers socializing with bevies of lovely French girls, obviously enjoying themselves. “Not as evil as alleged,” applauded the caption, urging a positive view of the occupiers.

Resources, meanwhile, grew even scarcer as the ceaseless influx of weary refugees shambling through Gray, traveling back to the homes they had fled just a few weeks before, swelled the numbers of homeless and hungry. To assist them, Monsieur Fimbel established a welcome committee and opened a shelter in a girls’ school just up the street from the Günzburgers’ vacant apartment. In the Ermitage Sainte-Marie, they served six thousand three hundred free hot meals between June 21 and August 6, while also providing new German-approved visas, coupons for gas, and a wall on which distraught travelers could publicly post pleas for news of lost family members and information on how to reach one another.

It was here, somewhat dazed, locked out of his apartment, and gripped by fear over the fate of his family, that Sigmar spotted Joseph Fimbel. Though shamed by his filth, Sigmar fell into the tall Marist’s arms and, abandoning his usual reserve, allowed himself to take comfort—the first he had known since his arrest—in the enveloping warmth of the other man’s friendship. Dry sobs choked his words, then, reverting to German, he started to stammer out questions.

“

Meine Familie?

” he asked. “They are not home! Where is Lisel? Janine and Trudi? My sister and Bella?” He did not pause for an answer before he had listed them all.

Monsieur Fimbel described his trip with the women to Arnay-le-Duc just two weeks before and tried to assure him that, almost certainly, they had run farther south from the path of the German incursion and would make their way back as soon as they could. His eyes smiled through thick glasses. “Have trust in the Lord,” Monsieur Fimbel said, invoking the God that both of them shared. “Patience. I know He will bring them back safely.”

Sigmar was hardly alone, however, in his distress. The prefecture of Vesoul estimated that 18,500 residents of the Haute-Saône who had joined the desperate flight south had yet to return to their homes in the region.

La Presse Grayloise

spoke to the awful doubts plaguing countless others not only in Gray but in towns and cities all over the country: “Many Graylois have come home this week; each day we see the return of friends for whom we were worried; in friendship we embrace one another with tears in our eyes. But there are still so many missing. Where have they gone?… The current impossibility of any communication by mail only makes our painful uncertainty all the harder to bear.”

At the end of the month, Sigmar’s women were transported back to Gray in a hearse. Considering the fact that they had traveled to Vichy by ambulance, their mode of return might have seemed tragic, but the choice had more to do with the state of the times than of their health. Their driver was a former acquaintance of Marie’s, who borrowed the hearse from a friend in the funeral business because he had no other means to ferry them all. It was an open hearse that attached to a car, and while Marie and Alice sat inside with the driver, Janine, Trudi, and Bella perched in the trough reserved for the coffin. In case of rain, they were armed with an umbrella.

In spite of its heavy occupation by Germans, Alice had insisted on returning to Gray in hopes of reconnecting with Sigmar. She was sick with worry, not knowing what might have happened to him, locked in prison when France was defeated. In Vichy, after leaving the hat shop, Alice and the others had moved into a rented room where each night, out of the depths of sleep, her unconscious wails gave voice to the tension she stifled all day. Her fear for her husband and uncertainty over how best to protect her daughters played out in nightmares, as she tossed and thrashed under the covers of the bed that they shared. By the end of a week, she announced her intention to leave, asserting that she would feel safer in occupied Gray with Sigmar—God willing they’d find him!—than here in unoccupied Vichy without him.

It was a long and uncomfortable ride during which they crossed paths with what looked like the entire German Army, pressing ahead in triumphant good cheer from the opposing direction. From the backs of their trucks, young

Wehrmacht

soldiers waved their caps in the air as they passed and even dared smile and shout greetings to Janine and Trudi. But leery of attracting attention that could result in their being stopped and forced to show identification papers revealing them to be stateless and Jewish, Alice ordered them to keep their heads down, avoid all eye contact, and pretend to be sleeping. After riding for hours on bumpy backcountry roads, Janine awoke from a nap to find that a call of nature that had begun as a whisper outside of Vichy had now, inconveniently, turned into a roar.

“Just squat inside the open umbrella,” Trudi advised her. But with an unending convoy of German trucks passing, Janine rejected her sister’s idea and knocked on the driver’s rear window to ask him to pull off the road for a moment. Then she ran by herself into the woods, hurriedly pulled off her panties, and dropped to the ground.

“

Halt! Was machen Sie hier?

” a loud voice demanded behind her. She whipped around to see four German soldiers aiming their weapons straight at her back, and she froze in terror, heart thumping, like a rabbit caught nibbling garden petunias. One of the soldiers pointed his gun barrel toward the panties that Janine still clutched in her hand, and they all burst out laughing.

“

Allez!

” the soldier in charge ordered in French as she cowered before him, trembling, uncertain whether they intended to grab her or shoot her if she attempted to run. Still aiming his weapon, he jerked his head past the woods toward the roadside where the hearse was parked waiting, and the soldiers’ laughter continued to ring in her ears, not only until they reached Gray but for decades that followed.

The first person they met when they finally drove into town turned out to be the wife of the fellow German prisoner with whom Sigmar fled Langres. The hearse was mounting the rue du Marché when they saw the woman from Freiburg, by now a more familiar acquaintance, emerge from a shop.

“They’re back, your father is back!” she called out to the girls, who sat numbly surveying the rubble around them. At the car window, she told Alice their husbands had made their way home a few days before, and she advised looking for Sigmar in the shelter set up at the school on the avenue Victor Hugo, luckily spared the worst of the bombing.

“Who knows?” The other Frau Günzburger shrugged, shaking her head, when Alice expressed alarm as to why Sigmar had chosen a shelter instead of going back to their own apartment on the very same street. “Maybe he couldn’t get in. Perhaps he just couldn’t face the idea of being alone there without you.” Then, too, she added, gesturing to the crush of shoppers lining the pavement behind her, he probably didn’t have money or food. “It’s

schrecklich

, there’s nothing to eat here but

Dreck

,” she grumbled in German, heedless of who overheard her. “The Nazi dogs are keeping it all for themselves. We’re practically starving, but

Gott sei Dank

, we’re still alive and together.”