Crossing the Borders of Time (26 page)

Domicile? The answer,

Gray

, is one André Fick wrote in script at least four times the size of any other word on the card. But as to nationality, he scrawled a response in letters so tiny, obscured beneath the stamp of the city, that even with a powerful magnifying glass, the answer remains intentionally indecipherable.

Decades later, when I sat with him in front of the fireplace of his tidy home, André remembered that Trudi and Malou had found his fondness for Janine amusing. Trailing behind him, openly giggling, they made him self-conscious when he walked the streets, already feeling confused and troubled by such tender yearnings for Janine as bred guilt in the face of his spiritual goals. His longtime intent of following in his role model’s footsteps—he still recalled confessing to her—would require affirming the same Marist vows that Mayor Fimbel had taken and bar him from marriage. Yet he had despaired that his affection for Janine pointed to weakness that might preclude a celibate life.

“I envisioned our having a future together,” he said of Janine. Nostalgia for the long-lost girl who awakened desire overwhelmed the fact that his wife, Marguerite, was seated beside him. “But in any event, Janine said no to my vision. As she was a Jew, and I was Catholic, it just couldn’t work, especially given the state of the world.”

What went unsaid in 1940 and again in 2001 was that Janine had already given her love to another French Catholic who came from Mulhouse. And while Roland seemed as remote to her during her time in Gray as a matinee idol, his claim on her heart precluded all other suitors. Indeed, Janine’s love for Roland had grown stronger. It burned bright and pure, untarnished by any sort of careless word or fickle deed that may dim love’s ardor when, being together, a couple take each other for granted.

The

Kreiskommandant

in charge of the town was fiftyish, a

Wehrmacht

reservist called back to duty to sit at a desk, not a young, rabid Nazi flexing his muscles or a man like the captain in breeches and boots who daily rode his powerful horse through Gray’s humble streets, making a splendid show of himself. That is how André Fick recalled the top officer who figured in my mother’s account like a cipher, a symbol, a uniform only, a hollow man in whom I might see all of Nazism’s evils or view as the rote overseer of an occupied town.

Every few days after beginning her job with the mayor, Janine entered this

Kommandant

’s office and proffered the laissez-passer, or

Ausweis

, papers to sign while she stood at his desk and considered the way he handled this work. Subordinate officers streamed in and out, the telephone rang, and weightier matters demanded attention, distracting his thoughts. The Führer’s black eyes glared at her from a framed photograph affixed to the wall, but the

Kommandant

was polite in his dealings and rarely demanded more information than the papers provided. As weeks wore on, she wanted to think he was growing bored by the process, that he rushed through it faster, with less concentration, whenever the sheaf she presented was thick. On pressure-filled days, he barely bothered to read the applicants’ names and their destinations, and while there were other instances when he eyed them sharply, she gradually started feeling emboldened. She moved closer in to his left, leaning over the desk, and ventured flipping the pages for him—a considerate girl—so the tops of the sheets, including applicants’ names, were partially hidden. She also dared some brief conversation, assuming her French was better than his and that he would not detect a German accent that would betray her refugee status and reveal her as Jewish.

A scheme had started to form in her mind: if she slipped an extra application into the pile she presented for signing, leaving blank the names of the would-be travelers, the

Kommandant

might unwittingly sign it, enabling her family to use the pass themselves. If the German officer noticed the error, she would pretend it was simply an honest mistake. “

Oh, je m’excuse!

” She practiced shock and dismay in front of the mirror, eyes round in horror, hands clasped to her chest. She would snatch the faulty application away, berating herself with abject disgust. “But how can this be? What a stupid mistake! I don’t understand how this could happen,

Herr Kommandant

!” What would he do? Would he instantly guess she had done it on purpose or chalk it up to her youth and sloppy work habits?

In mid-November, Janine decided to act, but resolved not to discuss it beforehand with anyone. She did not need to hear the dangers sketched out, as she had already done so in ample detail to frighten herself. Nor did she want to invite attempts to dissuade her, which she feared might be easy. Two weeks earlier, the Germans had suddenly evicted them from their apartment on the avenue Victor Hugo, its convenience as an officers’ lodging, just steps away from the

Kommandantur

, having attracted official attention. While Sigmar suspected that the landlord no longer felt comfortable renting to Jews and had offered it up to the occupiers, the Germans in any event requisitioned whatever homes and buildings they wanted. Mayor Fimbel had helped the family relocate, yet merely venturing out on the street grew ever more perilous, and Sigmar was gripped by the urgent need to escape.

And so, as Janine steeled herself to proceed with her plan, she yearned above all to impress her father, who was bound to be grateful and think her resourceful; yes, among all her motives that one stood out—the ever-present, aching compulsion to gain Sigmar’s respect. To rescue the family—what could be better? It excited her, too, to imagine telling Roland how she had managed all on her own to bring the family over the line, because if ever they managed to wiggle out of this dull little town, perhaps she would even be able to find him!

She resolved to act on a Monday, when the pile of applications had grown over the weekend, and she slipped in her own close to the bottom, by which point in his labors she hoped the

Kommandant

’s attention would flag. She shrank from the thought of arousing his anger—a thunderous storm she had already witnessed—so the ruse had to work the first time she tried it. If it failed, and he caught her “mistake,” she would never dare seem so careless again. At the very least, if he noticed the application lacking a name, the German would loudly complain to the mayor, and that, she knew, would embarrass her father by reflecting unfavorably upon Monsieur Fimbel. Clearly, it might also result in her being discharged.

Over and over Janine played the scene out in her mind. Still, she had not anticipated having to lean on the

Kommandant

’s desk to steady legs that threatened to buckle or that her pounding pulse would thrum so loudly she thought he could hear it. The

Kommandant

was signing the papers, and, as she turned the pages for him, her heightened state of nervous alert exaggerated every detail: the metal scratch of his fountain pen as it changed people’s lives, the tick of his watch, each dark hair or meandering vein on his bureaucrat’s hands, the late-day stubble that shadowed his jaw, the roll of skin that bulged like a

Wurst

over the back of his uniform’s collar. She tried to ignore authority’s trappings in favor of things that made him more human: generously, she attempted to picture a sweet-faced wife, children who missed him and longed to hear the clack of his bootstep nearing their door.

Janine’s nervousness grew with each paper he signed, approaching the one on which she depended. He paused, pulled out a box of cigarettes, absently tamped one down on his blotter, lit it, sighed, and leaned back in his chair. For one crazy second, she considered asking for a cigarette to bring home to Sigmar, like a big, shiny bow on top of the gift of a signed

Ausweis

. But she forced herself to encourage the

Kommandant

to get back to task: “

Nous en avons beaucoup aujourd’hui

,” so many today, she observed in a tone meant to apologize for the added burdens she brought his office. “

Oui, zu viel

,” too many, he said, awkwardly mixing both tongues, but he glanced up and gave her a resigned smile before bending back to the tedious job. She averted her eyes, afraid her delight would give her away when he signed hers.

“

Gut. Fertig

,” he said, finally done. He screwed the top on his pen, stood the sheaf on end on the desk, straightened the edges, and placed them back in the folder he handed to her. He had clipped together the ones he denied and made no mention of any on which the applicants’ names had been missing. “

Merci, mademoiselle

.”

“

Vielen Dank, Herr Kommandant

.” Gratitude bloomed in her heart so sincerely that she forgot where she was and answered in German. Then she turned and hurried out of the room, eager for privacy to rifle the file for the paper she wanted.

“

Auf Wiedersehen!

” the amiable soldier who always sat guard outside the

Kommandant

’s office, eager to flirt, called down the stairs. But before his words could pierce the bubble of joy in which she was floating, the red door to the street banged shut behind her, and she was gone.

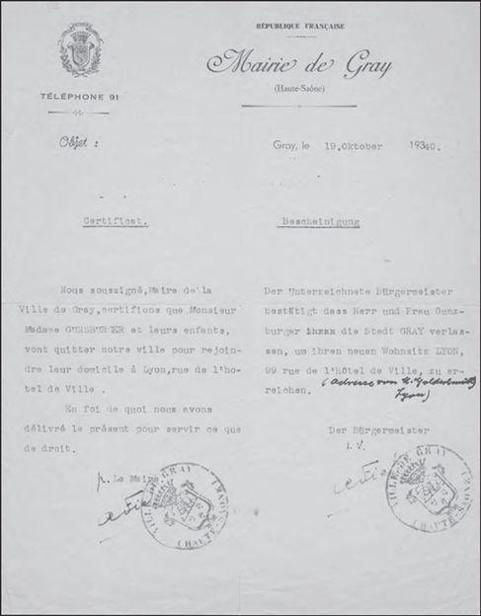

On November 20, 1940, André Fick came to see Janine off at the station, and they exchanged farewell gifts. She had painted a little landscape for him, a tranquil house in a sunny setting, and he had saved his limited pay to buy her a gold-plated bracelet. Who could say when, if ever, they might meet again? It worried André to see Janine head into the unknown, all the more when he discovered that the family’s arrangements called for her to travel by train through the Occupied Zone without so much as her father’s protection. Monsieur Fimbel was driving Sigmar, Alice, Marie, and Trudi straight to the border, where the mayor would add his official support to get them across. But his car couldn’t hold more than five people or their many valises, so Janine was leaving by train one day ahead of her parents, accompanied by Malou, who was moving to Lyon to attend dental school.

Besides being encumbered with a dozen pieces of family luggage, the girls were charged with added responsibility for Bella and her sister, Pauline, who had unexpectedly turned up in Gray two weeks before, begging to add her name to their papers. To make matters worse, the two aging sisters all too closely resembled the ugly propagandist depictions of Jews widely being displayed by the Nazis. And the fact that ulcerous sores on Pauline’s swollen legs made walking slow and painful for her did not augur well for quickly escaping from tight situations. Beyond such immediate doubts as to the wisdom of Janine’s traveling unguarded, André also realized that life in the Unoccupied Zone would not necessarily guarantee German Jewish refugees the level of safety they seemed to expect. This impelled him to prepare another, more important farewell present: two letters, carefully worded on official Gray City Hall stationery, both misspelling the family name (using an

s

instead of a

z

) to make it more French.

In the first, written in both French and German but aimed at appeasing the Germans in case the refugees were stopped en route, he falsely attested that “

Monsieur and Madame Gunsburger and their children will leave our city to return to their domicile in Lyon

.” As their address he cited the Lyon apartment that actually belonged to Marie’s daughter. In the second, meant for the French under Pétain, he provided a character reference: “

I

,

the undersigned Mayor of the City of Gray, certify that during the entirety of their stay in our city, the family S. Gunsburger has conducted itself in the most satisfying manner and has always demonstrated the best Francophile feelings

.”