Crossing the Borders of Time (55 page)

In the fall of 1948, Sigmar and Alice left the city for a few weeks’ visit with Heinrich’s family in Buffalo. This annual pilgrimage and a two-week summer stay at a lake in the Catskills—he reading, she knitting—were the couple’s only forays from the confines of their small apartment where their daily lives were governed by routine and economy. Already sixty-two when he reached the States, Sigmar had not attempted to get a job. Instead he worked at learning stratagems of stock investing—this notwithstanding the fact that his prospects for growing capital were significantly diminished when the great inheritance he had anticipated in America proved much smaller than expected. His original large bequest from one wealthy older brother had dwindled throughout the many years he couldn’t claim it or direct the way it was invested. And the widow of another older brother who had died childless many years before, leaving a vast estate and similarly generous bequests to his siblings, had managed to circumvent the will to her advantage. Yet when Sigmar’s surviving brothers and sisters sued to win their lawful shares, he refused to go along with them.

“

I

should sue my brother’s widow?” Sigmar demanded with incredulity, denouncing his siblings’ lawsuit as an ugly tactic, regardless of her assets or greedy machinations.

What money Sigmar gained from the first inheritance went to repaying with interest all his debts to Herbert, Maurice, and Edy, and the balance he endeavored to invest. Every day he went to Wall Street to learn beside his cousin Max, who was trying to become a broker. In the risky ventures of the market, though, Sigmar’s belated apprenticeship proved more costly than profitable. He watched, now in helpless indecision, then in loyalty to those few stocks he termed his “darlings,” as the value of his holdings fell. In that context, calling home one day from Buffalo, he told Janine to search his files to verify the purchase price of shares that now seemed poised to plummet even lower.

The blinds were drawn and everything in tidy order in her parents’ second-floor apartment when Janine, then ten weeks pregnant, sat down at Sigmar’s mahogany keyhole desk in the living room. Above her head, a large framed picture of President Franklin D. Roosevelt reflected her father’s gratitude to his new country. After years of living with the visages of Hitler and Pétain leering at him everywhere, Sigmar had uncharacteristically sent away for this poster-sized artistic tribute to FDR, believing, with many Jewish refugees, that the patrician wartime president had done his best to rescue them. (That Roosevelt had failed to open the gates of immigration to Europe’s victims anywhere near as widely as he could have, or that his administration had refused to accede to Jewish pleas to bomb the railway lines leading to Nazi death camps, were facts not yet known.)

In years to come, Janine would not remember whether the financial statement Sigmar needed had been difficult to find, obliging her to expand her search of his private files, or—she acknowledged the possibility—it was random, audacious snooping that broadened her explorations. Either way, like Pandora, she would regret her curiosity, when drifting from the broker’s statements, her eyes picked out a telegram from the International Committee of the Red Cross. It announced that a Roland Arcieri had enlisted help in France through the Red Cross Tracing Service to determine the whereabouts of a Janine Günzburger in New York. In the event this message reached her, the Red Cross instructed her to get in touch—promptly, please.

In an instant of total joy she forgot the sorry waste of tortured years, forgot her husband, forgot the child nestling deep inside her, and she responded to the wondrous fulfillment of her greatest wish: finally, finally, Roland was calling out for her! At last, after all her years of patient waiting, here was clear-cut proof of Roland’s enduring love. Yes, with the urgency of a telegram, her lover was crying out to her.

In a fever of excitement, she studied the telegram for directions on responding. But when had it arrived? She read it again, flipped it over, hunted vainly for its envelope, but no date could be found. Why had no one shared this with her? A cloud of dark suspicion slowly slid across her heart. Months or even years could well have passed since this telegram arrived. She struggled with the realization that its burial among Sigmar’s papers was proof that he had purposely concealed it. The ground tilted underneath her feet. The father whose steely dictates she had always feared, but whose honor she had never doubted, had acted with unconscionable deception.

A wave of nausea seized her. She fought for breath, her legs felt weak, and the room began to turn: Roosevelt, so solemn in his business suit, the violets with their velvet buds uncurling on the windowsill, Lindt chocolates in a porcelain dish that Alice offered every guest, the

Aufbau

’s latest issue folded on the coffee table, a cut-glass ashtray next to Sigmar’s reading chair—all these ordinary objects now seemed sly and slippery. Like painted scenery on a stage, her parents’ gemütlich living room disguised a disappointing world of secrets and duplicity. She gripped the corner of the desk. An unaccustomed sense of rage and violation overcame her, and she did not know what to do with it. Her thoughts went racing backward in useless search of explanations to make forgiveness possible.

Did this mean there had been letters too? Obviously so! Her love had written, begging her to come to him, and not receiving any answer, Roland could only have concluded that his letters failed to reach her. Why else would he have turned to the Red Cross Tracing Service? But hadn’t Norbert given him her address when they got together in Lyon? Then surely he had written her! How terrible for him, through years of doubt and silence, to be misled into believing that she had forgotten him. With eager fingers and frantic determination to understand the truth of things, she ransacked every drawer of Sigmar’s desk, certain that if he saved the telegram, he must have saved the letters too. Surely, the telegram was proof that Father would not have dared destroy them. But there was only that one telegram, saved from the incinerator by its officious pedigree, the sort of communication, she recognized, that no true German like her father, mindful of proper record keeping, would carelessly obliterate. Suspended in time—with a past that now demanded reevaluation, a present that no longer seemed of her own making, and a future robbed of honest choices—Janine spent hours on the floor of her parents’ living room, debating where to go from there. No point in raising the issue with Father. He’d cite his rights—no, his

obligation

—to protect his lovesick daughter from the dangers of pursuing an ill-advised relationship. Sigmar would not admit to doing wrong, and it would only drive a wedge between them. And so, respectful of his authority and still devotedly committed to winning his approval, she worked to squelch the anger to which she was entitled.

Beyond that, she numbly granted, she could hardly bring the issue to the open without involving Len and showing him how much Roland still mattered to her. Why hurt her husband now and taint their marriage, when she couldn’t leave him anyway? For how could she sail back to France anchored by an unborn child? She was fixed to the spot by the growing weight of me within her womb. The golden moment when she might have set a different course was as lost in clouded history as an intercepted telegram hidden in a file drawer.

At the end of 1949, Janine would be cruelly tested once again when her first employer, Dr. Morton, forwarded a letter that he had just received from Montreal. It was written by a stranger with a graceful hand, dated Christmas Eve, misspelled her name, and included no mention whatsoever of Roland. All the same, Janine instantly recognized his part in it. Most amazing, Roland seemed to know that she had married (perhaps via Edy and Lisette and the busy rumor mill of Mulhouse) and yet was looking for her anyway. He had already crossed the ocean! He was already on his way to her.

Dear Sir,

A friend of mine just arriving from France for a trip in Canada and the United States would like to get in touch with an old acquaintance: Miss Jeanine Gunsburg.

Miss Gunsburg was working for you a year or two ago, and we only know that she got married since then.

You are the only person to whom we could ask any informations connected with the name of her husband and her new address.

If it is possible, would you kindly send me back those few informations at the address below. Thanking you in advance for all the trouble.

If not for me, she would have run to him. My mother often told me so, and she still remembers the silent torment of longing to write back to Roland’s friend, though she knew it was too late. Incapable of absconding from her marriage with me

or

without me, she could not allow herself to write to Montreal. She passed her days in a fog of unspoken anger and sadness, desperate to reply, but stymied by the fear that if Roland arrived to visit her, she could never let him leave again. Any contact would be too dangerous. Her dream had come in search of her, and now she had to hide from it.

I have always shouldered a sense of accountability. At a moment when she might have grasped the freedom to take her chances with Roland, it was I who held her captive. Any wonder that beside my fascination with her romantic story, I felt an overwhelming need to protect the mother I adored—to make her

happy

, which would often pit me against my father. I needed him to help me validate the choice she made; instead, as time went by, he would insist upon pursuing an agenda all his own.

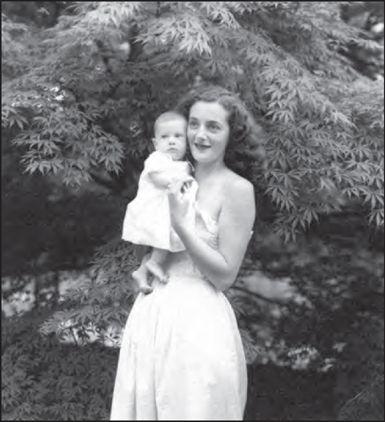

Janine and Leslie

In that same month that Janine forbade herself from replying to Roland’s intermediary in Montreal, Norbert came home from Germany for Sigmar’s seventieth birthday and brought the parents devastating news of his aim to marry a German woman he had met five years earlier, shortly after landing back in Europe on VE Day. He had met his intended wife while working as chief investigator for a Special Investigations Section of the United States Military Police stationed north of Frankfurt, and he knew his parents would be horrified. After all, what could be more difficult for them, more humiliating before their friends, than for their son to bring home a German Gentile war bride? Like Janine before him, Norbert was torn between the one he loved and duty to the family. But throughout his visit, he kept his plans a secret both from her and Trudi, and the parents peculiarly kept it from his sisters also.

After he went back to Germany, an emotional exchange of letters between parents and son smoldered for many months, with Norbert’s reading like the ravings of a youth at least a decade younger than his twenty-nine years. Madly, he waffled back and forth in a show of turmoil and confusion, confessing that his prolonged stay in Germany “was

not uniquely due to my love for my work or certainly not for my sympathy for Deutschland

.” Rather, he had struggled unbearably to weigh “

sentimentality against reason

,” and as emotions had finally prevailed, he wanted permission to marry the woman of his choosing. Evidently pained, he outlined his dilemma to the parents, even as he promised not to marry without their blessing:

Is it better to be unhappy without her but with you; or with her, but not with you?… In your answer, please do not threaten me with a thousand possible things.… I could never be happy in a marriage that goes against your will. If I could ever be happy by submitting to your possible disapproval, only time will tell.

Ever after, Alice preserved Norbert’s letters along with drafts of the replies that she and Sigmar, with heavy hearts, labored over wording. Theirs show harsh phrases crossed out and sympathetic inserts composed in the margins. The stakes were high. Sigmar and Alice feared losing their only son, and Sigmar well remembered his own older brother Hermann, who had disappeared completely after marrying outside the faith. Hermann had emigrated from Germany when Sigmar was a youth, but was so afraid his marriage to a Protestant in London would crush his parents that he changed his name to Gunn and ceased all contact. Until their last breaths, Simon and Jeanette remained tormented over him. Many years later Hermann resurfaced in New York. For Sigmar, however, the grief his parents suffered was not forgotten; rather, it guided his pen to write cautiously to Norbert. He feared an unyielding attitude about his son’s intended bride might encourage Norbert to settle permanently in Germany, instead of returning home to make his life with the family in the States.