Crossing the Borders of Time (9 page)

FOUR

THE SIDEWALK OF CUCKOLDS

B

Y THE TIME

Hanna returned from Arosa in late 1937, the growing number of legal, economic, and social restrictions on German Jews had forced Sigmar to accept the urgent need to get out of the country. Their immediate world was shrinking around them, and escape had become his critical goal, never mind the loss of their home or his business. But he had waited so long that it was no longer easy to gain entry anywhere else. For months, he struggled to secure visas to immigrate to the United States, but with Jews by the many thousands seeking admission, his written pleas went unanswered, and his subsequent trips to the visa office in Stuttgart proved equally fruitless.

The following March, declaring a need for Lebensraum or living space in the east, Germany annexed Austria, where jubilant crowds welcomed Hitler’s troops into Vienna. Almost immediately, Jews were violently attacked on the streets, the women forced to their knees to scrub sidewalks and gutters. Mass arrests of Jews in Germany began in June, and soon synagogues in Munich and Nuremberg were burned to the ground.

At an international conference on the refugee question held that summer in France, at Evian on Lake Geneva, the scope of the problem loomed large. Many of the thirty-two participating countries offered sympathy. Very few offered asylum. Although a quarter of Germany’s six hundred thousand Jews had fled its borders since 1933, France had accepted only 10 percent of them. With Austrian Jews now swelling the tides of refugees, the British not only tightened restrictions for England but also refused to accept Jews into Palestine. American quotas were kept tightly in place, as polls showed that the majority of Americans viewed Jews negatively and believed them to be a threat to the nation. Those who sought to curb immigration argued to President Franklin Roosevelt that the Depression still demanded putting domestic needs first. As a result, between 1933 and America’s entry into World War II eight years later, only about one hundred thousand Jews were admitted.

“It will no doubt be appreciated,” an Australian delegate announced at the Evian conference, “that as we have no racial problem, we are not desirous of importing one.” And Canada said that in terms of welcoming refugees, “none was too many.” Afterward, it was bitterly noted among Germany’s desperate Jews that

Evian

spelled backward yielded

naïve

, which was what they saw their hopes to have been, when they expected the conference to offer them someplace to go.

Sigmar now aimed his efforts at France, believing that what remained of the small building supply business he had launched in Mulhouse before he was married, along with the fact that his sister lived there, might help win admission. Then perhaps they’d have greater success winning American visas as “stateless” refugees stranded in France, he reasoned, than they’d experienced applying from Freiburg. And so, week after week, Sigmar traveled to the French consulate in Karlsruhe in pursuit of French visas, and he hired agents both there and in Mulhouse to lead him through thickets of requirements and charges. While his sister Marie’s son, Edmond Cahen, a lawyer in Mulhouse, helped him with legal papers, in the end Sigmar was obliged to pay what he termed “a present to a certain gentleman” in Mulhouse, a lifesaving bribe, to obtain the French visas he guiltily realized others might not have afforded.

By the time the family managed to leave, Sigmar was impoverished: he and his brother Heinrich were coerced into paying more for the privilege of fleeing than they received from the forced sale, at only a fraction of its true worth, of the prosperous firm they had founded in 1919. On April 7, based on an official ruling by the Freiburg Chamber of Commerce, two other brothers—Albin and Alfons Glatt, who had worked for competitors of the Günzburger brothers—took over what the chamber described as the “non-Aryan” firm, along with its buildings and vehicles, its warehouses full of supplies, and its ample customer lists.

Alice with Sigmar (L) and Heinrich, his brother and business partner, in Freiburg, mid-1930s

(photo credit 4.1)

As to the house at Poststrasse 6, Sigmar sold it to his next-door neighbor, August Schöpperle. The hotel owner was confident that the political turmoil and migrations of war would bring even more travelers with money to Freiburg and was planning to use it to expand the Minerva. In haste to depart by the time their papers came through, Sigmar had been in no position to bargain and had sold Herr Schöpperle the house at a price that was also far below its actual value. But it hardly mattered, he grimly acknowledged, given the fact that he was barred from taking money out of the country.

The Poststrasse, with the Hotel Minerva at the corner. Beside it to the right is the Günzburger home at Poststrasse 6

.

(photo credit 4.2)

Technically, it was arranged that “all things happened legally,” Dr. Hans Schadek, then Freiburg’s chief archivist, explained when he showed me the relevant records on one of my visits. He described how, seeking funds for armaments, the Nazis pillaged Jewish wealth by means of imposing taxes that conveniently managed to total the sum of every emigrant’s assets. Revenue from the sales of the family’s home and business was deposited into blocked accounts at the Oberrheinische Bank that were nominally in the Günzburgers’ names, but from which they could make no withdrawals without state approval. No such approvals were granted. Official taxes on “Jewish wealth,” flight taxes, bank fees on the taxpaying transactions, and punishing fines would eventually claim all that they owned through pretexts the Nazis wrote into law.

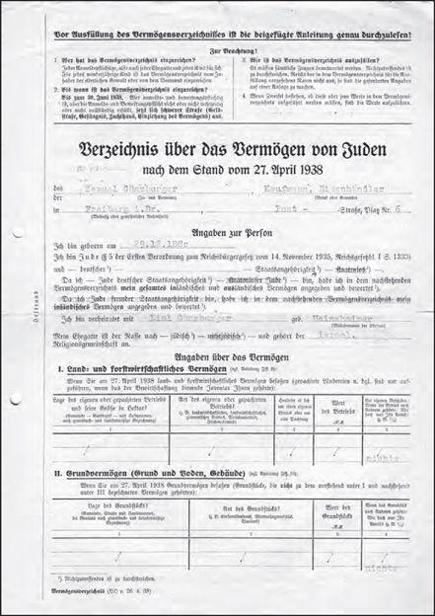

“

Ich bin Jude

” (I am a Jew), read the form Sigmar was obliged to fill out on June 30, 1938, before emigrating, declaring his remaining worth at that point. And for this purpose, it also described him as a member of the German state, no longer a citizen, yet still subject to the rules of the Reich. Having already signed away everything, however, there was nothing much left for him to declare. Almost every category of assets on the four-page form thus earned the same answer:

Nichts

(nothing). Money?

Nichts

. Real estate?

Nichts

. Other expected capital?

Nichts

. The only items of any value still in his possession besides their furnishings were three now-dubious life insurance policies, a gold watch, and the simple gold rings he and Alice had exchanged at their wedding.

All this brought them to the warm mid-August morning in 1938 when they were to leave. Hanna, now almost fifteen, awoke to the familiar cooing of doves on the rooftops and the buzz of the electric cart ferrying mail to the post office at the end of the street. From the Hotel Minerva next door came the familiar clatter of dishes and pans, the smells and the banter of the kitchen staff preparing guests’ breakfasts. It had always been a private pleasure for her to sit at the window and spy on the sophisticated foreign tourists who lingered on the hotel terrace, enjoying their food and their papers and quietly conversing. Now she, too, would be traveling, but the mysterious thrill she had always imagined as she studied those tourists was replaced by dread in leaving her birthplace for the unknown.

The official form—the Inventory of Jewish Wealth, in accordance with the Reich law of April 27, 1938

—

on which Sigmar reported no longer having any assets: “nichts”

“

Wir wandern aus. Wir wandern aus

,” her father had warned them so many times without her ever believing he meant it. The verb he had used means

to emigrate

, but also—too aptly, she feared—to wander, to roam, to travel like nomads.

Across the room, her beloved Käthe Kruse doll drooped on a shelf, its painted blue eyes accusingly staring. Her only doll had been the patient in so many of her first medical efforts that, with its soft stuffed body scarred by long lines of stitches and stained in the cause of science by myriad greasy ointments, Hanna had already decided to leave her behind. They were traveling by train, but a van would carry their pared-down household possessions, including Sigmar’s cherished grand piano. To accommodate the smaller space they would have in their Mulhouse apartment, they were taking furniture only from the living room, dining room, and master bedroom. For the children, their beds. Art, silverware, crystal, and china found space in the truck. Clothes and books were carefully chosen. Still, they were uncommonly lucky to be able to leave with that much.

Once the truck pulled away, Sigmar approached the wide oak doorway with a little screwdriver. There were tears in the eyes of this man so ill accustomed to showing emotion as he reached up to unfasten the five-inch long carved wooden mezuzah that he had hung on the entryway of the house, creating space that was sacred, on the day that he and Alice moved in as newlyweds. Never adept with his hands, Sigmar took off his glasses and angrily wiped at his eyes as he tried to fit the slim head of the screwdriver into the slots of the two stubborn screws that held the mezuzah to the doorframe, welcoming those who entered the house. Once it came down, he saw the tight, yellowed scroll of parchment rolled up inside it with the familiar prayer inked by hand in minute Hebrew letters, admonishing faithful adherence to God’s commandments—among them the holy duty to teach His words to new generations.

Sigmar took that mezuzah wherever they moved in the years that followed, an artifact of a world destroyed, but he would never rehang it, as he never regained a home of his own. No, he never regarded his small New York City apartment as worthy of consecration by such an imposing ritual object; instead he nailed to his American doorway a small, unobtrusive version made of indeterminate metal. But twenty years after the day he ruefully carried it wrapped in his handkerchief over Germany’s border, Sigmar presented the Freiburg mezuzah to my mother and father, who attached it to the first house that they bought, the house my mother resolved never to leave, despite my father’s persistent entreaties and his efforts to lure her to bigger and better.