Crossing the Borders of Time (18 page)

Later and always, however, pricked by guilt, Janine would remember having been blithely trying on shoes at the very same time that the police were leading her parents away. So it is that the mind seems to stitch the unthinkable moment into the simple everyday fabric of the banal. We remember precisely what we were doing when tragedy struck almost as if we could posit some logic, some cause and effect, or some justice involved. Or at least, when rationale fails, there is time and place, the reliable signposts of chronology and geography, to provide some context for what has occurred. Ah yes, I remember exactly, I was doing

that

when it happened,

that

when I heard. Those pecan-brown loafers—who could forget them?

Early that evening, Alice returned home alone and exhausted. Dark circles shadowed her eyes above her sharp cheekbones, and she had removed the pins that generally held her hair in a ladylike coil, so that now her braids dangled over her shoulders, lending her the look of a girl. The police had taken her and Sigmar straight to the

gendarmerie

, she said, and held them in separate rooms for frightening hours of interrogation. Over and over, they had probed the same issues, as if they would jolt her or trick her into changing her answers, yet she could not figure out what they wanted to hear.

“

Vous êtes allemande? Deutsche, oui?

” You are German? one asked her. The description implicitly carried a tired accusation. “So, you tell us you worked in a German Army hospital in the last war. What brought you to Gray? Why are you here?”

But Sigmar’s record as a German Army war veteran troubled them more. With Hitler’s troops marching now in their direction—not through, but

around

the Maginot Line to the north—all foreigners were suspect. The French authorities thought it possible that Sigmar, then not quite sixty years old, had been planted in Gray, a spy for the Germans, a fifth columnist, and they could not take the chance of letting him go. Fear of sabotage raged as the

Wehrmacht

moved closer.

“Why did you come here?” the police demanded. “How long are you staying? Who are your contacts? How are you spending your time? If you’re not working here, where are you getting the money to live on? What was your business in Germany? Why did you leave there?”

Sigmar’s answers seemed irrelevant to them. “Very sorry,” they told him, “higher orders, of course, but we have to detain you.” How long they would hold him remained undetermined. Yes, they understood that he had escaped

to

France to get

away

from the Germans, that his only son was serving in North Africa with the

French

Foreign Legion, but they could not take the risk of allowing a possible enemy spy to remain at large with war erupting. They would hold him that night and move him in the morning to a fortress in Langres, a town about thirty miles northwest of Gray.

The charge? He was branded an enemy alien, a category in which he was far from alone. Under national law, they told him, they were rounding up all German men and many women between seventeen and sixty-six years of age among refugees in the region in case spies or sympathizers were hiding among them. The police captain confided to Sigmar that the group actually included another Günzburger, a man who also maintained that he had sought refuge in Gray after fleeing the Nazis in

his

hometown of Freiburg. Beneath the friendly façade of sharing a tidbit of information, the policeman’s tone was insinuating.

“You already know one another?” the officer said. “Interesting … And both of you Günzburgers just happened to move into Gray by coincidence only?”

In any event, urgent times required extra precautions. The officer shrugged. An exception in the regulations permitted him to let Alice go because Trudi was under sixteen; by virtue of youth, both girls were technically exempt from suspicion, while Marie and Bella enjoyed the protection of French citizenship. The officer in charge told Sigmar that during his absence—hopefully brief, as France would certainly gain victory soon—his female relations were welcome to stay on in Gray, and there was no reason to fear that they would be harmed. But had Sigmar heard, by the way, that spies for the Germans were so godless and crafty that some were thought to be hiding as nuns in the midst of the pious French population?

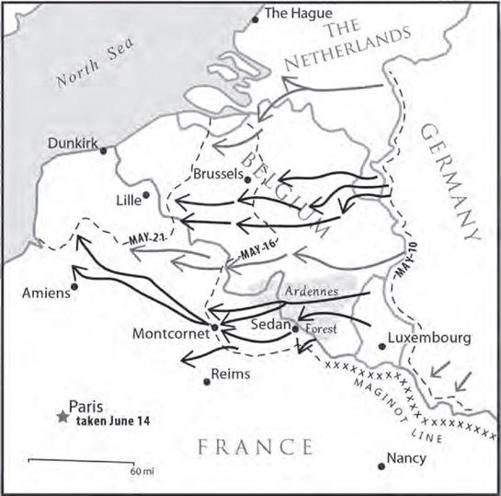

The German invasion of France that sparked Sigmar’s arrest began with Hitler’s assault on May 10, 1940, on the three neutral states of Luxembourg, Belgium, and The Netherlands, as Nazi troops slammed over the 175-mile front extending from the North Sea to the quickly irrelevant Maginot Line with a muscular phalanx of motorized infantry and fire-spitting, fast-moving tanks as had never been seen in warfare before. Hitler’s carefully plotted three-pronged attack aimed to divide his enemies’ forces. To the south, one German division played to French expectations by moving against the Maginot Line. To the north, the Germans drove into The Netherlands and Belgium, luring the strongest Allied divisions to mount a defense. And between those assaults, the Germans launched the most crucial incursion. Later dubbed the

Sichelschnitt

, or cut of the sickle, it sliced through the dense Ardennes forest of Luxembourg and south Belgium and from there into France near Sedan, above the northernmost point of the Maginot Line.

GERMAN INVASION OF FRANCE,

MAY-JUNE 1940

For all of the money and effort that had gone into constructing an impregnable barrier against Nazi attack, the Maginot Line simply did not extend far enough, leaving France’s 250-mile border with Belgium unfortified. Yet it had penned the French leaders into passive and outmoded thinking. Theirs was no match for the Germans’ fiercely aggressive approach to the war, any more than the creaky French air force could rival Göring’s fearsome

Luftwaffe

. Stunned by an onslaught from which they had felt secure and protected and disheartened by the prospect of battle, French leaders succumbed to defeat right away.

“We are beaten!” French premier Paul Reynaud despaired, wakening Britain’s prime minister Winston Churchill with a frantic telephone call on just the fifth morning into the war to sound the alarm that the fall of France was already at hand. Undeterred by the military might the Allies assembled—the bombers and fighters, tanks and heavy artillery, as well as ground force divisions amassed by the French, British, Belgians, and Dutch in a belatedly united campaign—the Germans had proved themselves more agile and mobile. They were practiced at smashing by land or diving by air over the borders of Europe, a wake of flames and of death trailing behind them. Once the Germans invaded around the stunted French fortification, any retreat meant inviting Hitler to penetrate farther. Among the French, there was little stomach for the scale of losses they had endured by the end of 1918, when they counted 1.3 million dead—one out of every five men between twenty and forty-five—as well as one million crippled among the eight million men called up to fight.

The German attack, moreover, came as France was already struggling to cope with a massive refugee problem. Defeat in the Spanish Civil War the previous year chased more than four hundred thousand Spaniards and disheartened volunteers from other countries over the border. The French interned many under inhumane conditions in camps like Gurs constructed along the Spanish frontier. Now, from the east, millions of new refugees surged through the country ahead of the German advance. In panic, German Jews, Poles, Belgians, Dutch, and Luxembourgers jammed the roads, overwhelming the French ability to deal with them while simultaneously fighting to hold back Hitler’s armies. The refugees—many of them stateless, impoverished, unable to speak French—helped fan the xenophobia already in place. And as half the 350,000 Jews living in France when the Germans invaded were recent arrivals, their numbers were viewed with mounting dismay.

By June 10, as the Nazi war machine continued its overwhelming drive across France, and as Italy, lusting for plunder, joined the struggle on Hitler’s side, the French government fled to Bordeaux from Paris, leaving the capital an “open city” for the victorious Germans to enter without firing a shot. On June 14, the swastika flew on the Eiffel Tower’s exquisite iron lattice. German soldiers goose-stepped under the Arc de Triomphe and toasted their victory on the Champs-Elysées. Less than a third of the three million residents of central Paris were still there, the rest having joined the terrified masses—comprising almost a quarter of the native French population of forty million—swelling the roads as they fled from their homes.

For the demoralized French Army, confronting civilian panic on so large a scale further disrupted their efforts to impede the merciless German assault. Many soldiers threw down their guns and simply deserted. Other divisions barely could move, wedged in place by the aimless masses searching for safety. By the thousands, the fleeing French poured into Gray from the north, crossed its Stone Bridge over the Saône, and headed toward Dole. With German troops ready to storm the town, Alice and Marie, desperate with fear, realized the time had come to join the exodus scrambling to run—farther west, farther south. They could not risk waiting for Sigmar’s return.

Nine months after the family’s arrival in Gray, in the face of dwindling public transportation, the Rosengart still sat parked on the street with no one to drive it. Aunt Marie had repeatedly urged Janine and Trudi to learn to drive, but after only two lessons they gave up, both preferring to spend their time with the

Eclaireuses

or French Girl Scouts, rolling bandages for the army. The sisters jumped at the chance of being included when Mayor Lévy’s granddaughter asked them to join, and they felt proud to help fight the Nazis. Besides, the small car regularly stalled, and they were embarrassed to have to climb out and crank it; and as neither Sigmar nor Alice knew how to drive, the girls saw no reason why they should, either.

Now, having no other recourse, trying to imagine what Sigmar would do to escape from Gray, Alice sought out Monsieur Fimbel. The plan devised by Marie—counting on her daughter-in-law’s resourcefulness to save them—involved meeting up with Lisette and her children in Arnay-le-Duc in Burgundy and then for them all to flee south together. Monsieur Fimbel agreed to take them that far, but said he would have to rush right back to Gray to be at the helm of his school when the Germans invaded. There was no time to tarry! He would drive Alice, Marie, and Bella in his own car and recruit one of his teachers to drive the Rosengart with Janine and Trudi. Assuming there was gasoline to be had, he counseled, they would undoubtedly find some other refugee in Arnay-le-Duc more than willing to serve as their driver. At worst, down the road, the car being valuable, they could use it to barter for other assistance.

The five women packed a small suitcase each and closed their door on everything else. Before leaving, Alice paused to write Sigmar a note in the event he escaped from Langres and got back to Gray before she did:

Lieber

Sigmar, We are going with Marie and Bella to join Lisette in Arnay-le-Duc and hopefully will move south from there. God willing, we will try to come back here as soon as we can. I beg of you, please take care of yourself!

Gruß und Kuß

. Greetings and Kisses, Your Lisel

The next few days’ travels made the trip from Mulhouse to Gray when war was declared the previous fall seem like a casual family outing. Their first stop, Arnay-le-Duc, northwest of Beaune, was a trip of just a few hours, which they made on back roads to avoid running into German divisions. They arrived to bedlam in the historic main square, filled with soldiers and refugees all in confusion and terror over what to do next. But in the midst of the crowd they found Lisette, who had shrewdly sized up the situation and instantly grasped that under the circumstances, it was

chacun pour soi

, each for oneself, and they had to be sharp to seize the advantage.

A fleet of empty ambulances was just preparing to pull out of the city under the escort of the retreating French Army. The best possible plan now, Lisette advised quietly, was for Marie, Bella, Alice, Janine, and Trudi to wangle a ride to safety with the ambulance corps. Meanwhile, she and her four children would seek cover at a farm owned by the parents of their governess in Brive-la-Gaillarde, if only she could think of a way to get there. When her eye fell on the Rosengart, Lisette asked Alice to lend her the car and began searching the square for a fresh volunteer to take the wheel. In her arms she struggled to carry Françoise, her disabled eight-year-old daughter, while her other twin daughter and two sons, then four and two years old, clung to the skirt of the governess who trailed behind her. Running to the French general in command, Lisette permitted herself to break into tears. She summoned every bit of helpless allure as she begged for compassion, pointing first to the group of women from Gray who stood self-effacingly off to the side; then at the children hiding behind her; and finally at the shiny, red Rosengart, still barely driven. The others watched in wide-eyed amazement as the general gave her his total attention, even sympathetically nodding at points.